|

|

|

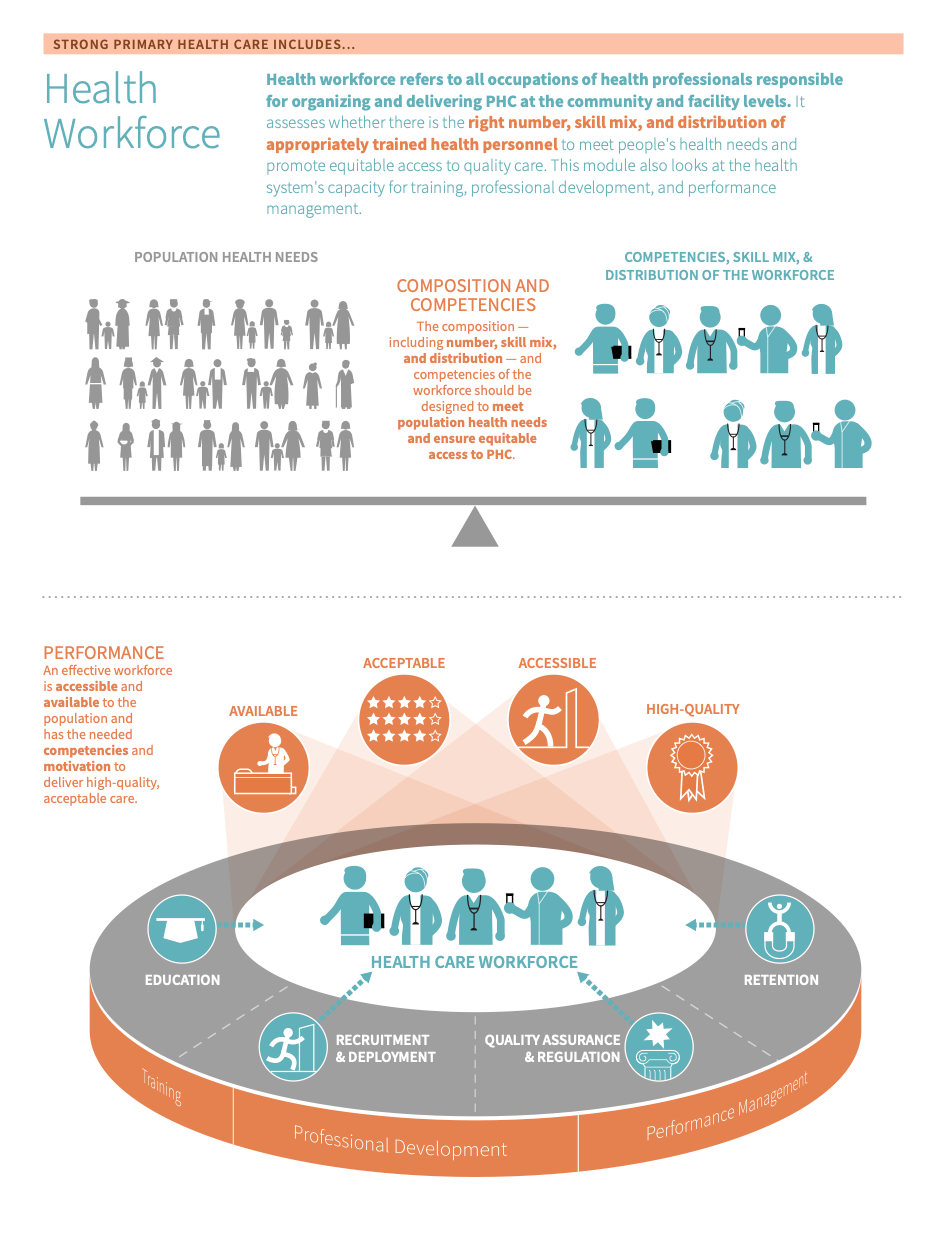

Building a strong PHC workforce is a critical component of health system strengthening efforts

A strong PHC workforce means that health professionals are skilled, motivated, and available to deliver high-quality PHC in line with changing population health needs

The term Primary Health Care (PHC) Workforce refers to all occupations of health professionals responsible for organizing and delivering PHC at the community and facility levels. 123 The PHC workforce is a subset of a country’s human resources for health (HRH). To simplify, we will use health workforce, the PHC workforce, and HRH interchangeably in this module.

Building a strong PHC workforce is a critical component of health system strengthening efforts. 12 The strength of the PHC workforce can be measured or understood via the following dimensions:

- The extent to which the number, Skill mix Skill mix describes the combination of different occupations of health workers (i.e. doctors, nurses, and midwives) in a primary care practice in terms of numbers, diversity, and competencies. , and distribution of the workforce meets changing population health needs and promotes equitable access to high-quality PHC 12

- The extent to which the health system is capacitated to train and manage the performance and professional development of the workforce 34

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Read on to learn how to use country data to:

- Make informed decisions about where to spend time and resources

- Track progress and communicate these updates to constituents or funders

- Gain new insights into long-standing trends or surprising gaps

Countries can measure their performance using the Vital Signs Profile (VSP). The VSP is a first-of-its-kind tool that helps stakeholders quickly diagnose the main strengths and weaknesses of primary health care in their country in a rigorous, standardized way. The second-generation Vital Signs Profile measures the essential elements of PHC across three main pillars: Capacity, Performance, and Impact. Health workforce is measured in the Inputs domain of the VSP (Capacity Pillar).

If a country does not have a VSP, it can begin to focus improvement efforts using the subsections below, which address:

- Key indications

-

If your country does not have a VSP, the indications below may help you to start to identify whether the health workforce is a relevant area for improvement

- Access barriers: If patients cannot readily access a skilled health worker at their local facility or in their community, it may indicate that there is a shortage of health workers necessary to meet the demand for PHC services.

- Poor patient and provider experience of care: If patient and/or provider satisfaction is low, it may indicate that health workers do not have the capacity to deliver high-quality services. For example, staff do not feel safe and supported at work and/or providers do not have the skills needed to meet their patients’ needs and preferences.

- Poor clinical outcomes: If clinical outcomes are poor, it may indicate that health workers do not have the competencies needed to deliver high-quality services. It can also point to capacity gaps. For example, quality assurance mechanisms are poorly implemented at the point of care.

- Key outcomes and impact

-

Countries that strengthen their health workforce may achieve the following benefits or outcomes:

- Universal health coverage: Achieving the targets for UHC is dependent on having a sufficient number of skilled health professionals who are equitably distributed and accessible by the population. (3,5)

- Quality of care: a strong PHC workforce means care teams are made up of skilled health professionals with a diverse skill mix, helping to strengthen service delivery and maximize the quality of care for the patient, including the efficiency, timeliness, effectiveness, and safety of services.

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Explore this page for a curated list of actions to improve information & technology, which embark on:

- An explanation of why the action is important for information & technology

- Descriptions of activities or interventions countries can implement to improve information & technology

- Descriptions of the key drivers in the health system that should be improved to maximise the success or impact of actions

- Relevant tools and resources

Key actions:

-

As discussed above, competencies are a critical component of a strong PHC workforce. This helps to ensure that pre-and in-service training and practice align with population health needs and that the PHC workforce is capacitated to deliver on the core functions of PHC (first point of contact, continuity, comprehensiveness, coordination, and person-centeredness). 367

Key activities

National & sub-national levels

- Conduct an analysis of the health labour market. Understanding the health workforce profile will help policymakers define the need and scope of change, including priority areas for improvement and investment. 389

- Strengthen institutional capacities required for effective decision-making and governance of the health workforce. Key capacities include:

- Data on human resources for health (i.e. building and managing information systems, using them to collect and analyze data on HRH performance, etc.)

- Multisectoral coordination (i.e. mobilizing resources for a strong PHC workforce via advocacy, intersectoral negotiation, etc.)

- Innovation and learning (i.e. using research methods to identify gaps and improve HRH performance, implementing HRH innovations, etc.)

- Note: this activity is cross-cutting, and should be considered when implementing any/all of the key actions in this section.

- Align workforce education programs with the core functions of primary care and community- and population health needs. Reforming basic, in-service, and continuing learning content and methods will help to ensure that students and health workers have the they need to deliver high-quality primary care. 389 To aid in this step:

- Clearly define competencies for all occupations of the PHC workforce and use these competencies to define standards for education and practice. The primary health care workforce should have competencies related to people-centeredness, communication, decision-making, collaboration, evidence-informed practice, and personal conduct to enable them to provide the PHC service package. This helps to ensure that pre-and in-service training and practice align with population health needs and that the PHC workforce is capacitated to deliver on the core functions of PHC Well-defined PHC competencies are/include: 610

- Evidence-based. They also reflect the current status of the health sector, including the needs and expectations of the population (determined via a situation analysis)

- Adapted to the country context, meaning that competencies reflect the list of interventions at the PHC level and structure of the PHC workforce in the country.

- All key functions of primary health care: first-contact access, continuity, comprehensiveness, coordination, and people-centeredness.

- For additional guidance, see page 16 of the WHO’s report on building the PHC workforce of the 21st century and Objective 1 of their global strategy on HRH.

- Clearly define competencies for all occupations of the PHC workforce and use these competencies to define standards for education and practice. The primary health care workforce should have competencies related to people-centeredness, communication, decision-making, collaboration, evidence-informed practice, and personal conduct to enable them to provide the PHC service package. This helps to ensure that pre-and in-service training and practice align with population health needs and that the PHC workforce is capacitated to deliver on the core functions of PHC Well-defined PHC competencies are/include: 610

- Optimize the existing workforce by promoting teams with a diverse skills mix and optimal scopes of practice. Furthermore, ensure adequate incentives and decent working conditions for all team members. 389

- For additional guidance, see page 17 of the WHO’s report on building the PHC workforce of the 21st century and Objective 1 of their global strategy on HRH.

Facility level

- Use performance monitoring systems to continuously assess the ability of the PHC workforce to deliver on their defined competencies, addressing any challenges with imbalance, maldistribution, and interprofessional collaboration

- Ensure PHC health workers are trained in the necessary competencies and have acquired proper training by cross-checking (s) and/or (s). 10

- Keep a record of health workers’ certificates and validations of training. 10

- Institute continued professional development and periodic re-validation of credentials. 1011

- Create standardized procedures for when members of the health workforce do not meet the necessary qualifications or have not obtained the proper credentials. 1011

Community level

- Increase awareness of educational opportunities for those who join the PHC workforce.

- Promote demand for PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. that require training in the necessary competencies, such as via health information and literacy campaigns and community engagement platforms. 8

Related elements

- Policy & leadership

- Multi-sectoral approach

- Organisation of services

- Population health management

- Management of services

Relevant tools & resources

- WHO, 2022: Compendium of resources on health workforce training and education

- WHO, 2022: Compendium of resources on improving health workforce data and evidence

- WHO, 2022: National Health Workforce Accounts Data Portal

- Gupta et al., 2021: Approaches to motivating physicians and nurses in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic literature review

- WHO, 2021: Building the PHC workforce of the 21st century

- WHO, 2018: Building the primary health care workforce of the 21st century: a technical series on primary health care

- WHO, 2018: Guideline on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programs

- WHO, 2016: Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030

- Filipe et al, 2014: Continuous professional development: best practices

- USAID and Capacity Plus: HRH Global Resource Center

-

Maldistribution of the PHC workforce is a huge barrier to providing high-quality care for all.

Key activities

National & sub-national levels

- Improve the production and distribution of the workforce, particularly in underserved, urban peripheral, and remote areas where demand for PHC workers is the highest. To aid in this step: 389

- Establish an occupation of health worker in the country that provides proactive outreach and care to communities (i.e. )

- Stimulate demand for PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. via financial protection schemes and enhancements to PHC facilities and services. Proactive outreach can also help to stimulate demand for primary care.

- For additional guidance, see pagers 14 of the WHO’s report on building the PHC workforce of the 21st century and Objective 2 of their global strategy on HRH.

- Create PHC specialities in dentistry, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, public health, community health and social work. Furthermore, create policies and incentives that encourage medical students to pursue primary care. 389

- For additional guidance, see pages 18-19 of the WHO’s report on building the PHC workforce of the 21st century.

- Introduce and/or adapt policies and incentives for recruitment and retention. Governments should introduce a good mix of policies and incentives to attract and retain health workers, especially in underserved areas. 12 Examples include:

- Financial incentives (i.e. higher salaries, subsidies, cheap loans, fee-for-service payments, etc.)

- Professional incentives (i.e. ongoing professional development, supportive supervision, etc.)

- Personal and family supports (i.e. housing, transportation, education of children, and work for spouse)

- For additional guidance, see pagers 20 of the WHO’s report on building the PHC workforce of the 21st century.

- Improve the management of health worker migration flows and mobility.

- For additional guidance, see page 20 of the WHO’s report on building the PHC workforce of the 21st century.

District & facility levels

- Work with national level stakeholders to provide appropriate and such as loan repayment, and work to ensure a positive, non-discriminatory practice environment. 3172122232728

- For additional guidance, see the service availability and readiness module.

- Utilize effective management processes and increase accountability in order to optimize motivation, satisfaction, retention and performance of the health workforce. 12

- For additional guidance, see the management of services module.

- Re-organize care teams and operations depending on the setting, availability of resources and needs of the local community. 12

- For additional guidance, see the organisation of services module.

Community level

- Work to address the shortage of health workers in rural or underserved areas by recruiting students and workers directly from these communities. 13141516

- Participate in the selection and deployment of the PHC workforce at multiple levels (community, outreach, & facility levels). 12

Related elements

- Policy & leadership

- Multi-sectoral approach

- Adjustment to population health needs

- Purchasing & payment systems

- Funding & allocation of resources

- Population health management

- Management of services

- Organisation of services

- Service availability & readiness

Relevant tools & resources

- Pittman et al., 2021: Health workforce for health equity

- WHO, 2021: Building the PHC workforce of the 21st century

- WHO, 2018: Guideline on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programs

- WHO, 2016: Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030

- World Health Organization, 2016: Working for health and growth - investing in the health workforce

- Improve the production and distribution of the workforce, particularly in underserved, urban peripheral, and remote areas where demand for PHC workers is the highest. To aid in this step: 389

-

Quality assurance Quality assurance of the health workforce refers to systems for ensuring that the practicing primary health care workforce has the appropriate training and qualifications, that lists of those appropriately trained and qualified providers are maintained, and that appropriate measures are taken with respect to providers who do not meet established standards. mechanisms that span from education to practice are critical to ensure that the PHC workforce is equipped with and demonstrates the knowledge and skills needed to deliver high-quality PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. . As described above, mechanisms should ensure that education standards are established and enforced based on predefined PHC-specific workforce competencies, that all actively practising workforce are qualified to do so, and that quality standards are being met in practice.

Key activities

National & sub-national levels

- Develop normative standards, accreditation procedures, and evaluation activities to ensure quality service delivery and ethical practice. For example, countries should establish accreditation mechanisms and make them mandatory for all educational institutions and programmes. 810

- For additional guidance see the Objective 3 of their global strategy on HRH.

- Strengthen the capacity of regulatory and accreditation authorities (i.e. professional associations). Regulatory authorities (i.e. professional associations) should serve as the guarantors of quality service delivery and ethical practice in both the public and private sectors. To support them in this role, governments should actively involve them in policy dialogue related to the development and enforcement of standards and regulations. 389

- For additional guidance see the Objective 3 of the WHO’s global strategy on HRH and the policy & leadership module.

- Establish mechanisms for collaboration across labour, education, and financial sectors to ensure alignment around processes and regulations of PHC workforce education. 38912

- For additional guidance see the Objective 3 of the WHO’s global strategy on HRH and the multisectoral approach module.

- Collect more and better data on the health workforce: To support sustainable investments, policies, and systems for health workforce development, countries need robust workforce-related data--including workforce characteristics, remuneration patterns, workforce competence, performance, absenteeism, etc.--from the public and private sectors as well as the in-country capacity to analyze and use this data to inform policy-making and planning. 38917

District & facility levels

- Use protocol-based approaches and decision-making tools to make it easier for clinicians to readily access reliable, evidence-based content at the point of care. 38918 UpToDate is one such clinical resource that can give providers the informational tools they need to improve care.

- See pages 16-17 of the WHO’s technical series on the quality of care and the service availability and readiness module for additional guidance.

- Implement systems for performance monitoring and data-driven decision-making. To ensure adherence to safety and quality standards in practice, promote a continuous culture of quality improvement, and equip providers with the requisite training and resources needed to deliver high-quality services. Staff supervision is one form of applied, individual-level performance measurement and management that can improve provider competence and help staff deliver more effective services. 38918

- Learn more about systems for quality improvement in the management of services module

Related elements

- Policy & leadership

- Multi-sectoral approach

- Adjustment to population health needs

- Management of services

Relevant tools & resources

- WHO, 2022: Compendium of resources on health workforce training and education

- WHO, 2022: Compendium of resources on improving health workforce data and evidence

- WHO, 2022: National Health Workforce Accounts Data Portal

- WHO, 2021: Building the PHC workforce of the 21st century

- WHO, 2018: Guideline on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programs

- WHO, 2018: National Health Workforce Accounts Implementation Guide

- WHO, 2016: Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030

- World Health Organization, 2016: Working for health and growth - investing in the health workforce

- Develop normative standards, accreditation procedures, and evaluation activities to ensure quality service delivery and ethical practice. For example, countries should establish accreditation mechanisms and make them mandatory for all educational institutions and programmes. 810

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Understanding and identifying the drivers of health systems performance--referred to here as “related elements”--is an integral part of improvement efforts. We define related elements as the factors in a health system that have the potential to impact, whether positive or negative, the health workforce. Explore this section to learn about the different elements in a health system that should be improved or prioritized to maximize the success of actions described in the “take action” section.

While there are many complex factors in a health system that can impact the health workforce, some of the major drivers are listed below. To aid in the prioritization process, we group the ‘related elements’ into:

Upstream elements

We define “upstream elements” as the factors in a health system that have the potential to make the biggest impact, whether positive or negative, on the health workforce.

- Policy & leadership

-

Supportive HRH policies help to ensure substantive, strategic investments in the PHC workforce and the effective oversight, management, regulation, and distribution of HRH. Potential policy levers for HRH strengthening may include (adapted from the WHO’s technical series on building a strong PHC workforce):

- Policies on production (recruitment, enrollment, education)

- Policies to address inflows and outflows (recruitment, retention)

- Policies to address maldistribution and inefficiencies (skill mix, retention, productivity)

- Policies to regulate (quality assurance, continuing education, performance measurement and management)

Complementary elements

We define “complementary elements” as the factors in a health system that have the potential to make an impact, whether positive or negative, on the health workforce. However, we consider these drivers as complementary to, but not essential to performance.

- Multi-sectoral approach

-

Coordination with the education sector is a component of building a strong and competent PHC workforce. In other words, a PHC workforce that is well-trained and educated is crucial for delivering high-quality PHC and taking a multi-sectoral approach is a vehicle for doing so.

Learn more in the Multi-sectoral Approach module

- Adjustment to population health needs & population health management

-

It’s vital that a country’s PHC workforce addresses the needs of the local community and is equipped to handle the most pressing problems in primary care that are relevant to a specific area. Participatory and data-based priority-setting ensures that local health needs and available workforce are aligned. Additionally, local priority setting helps to ensure that the competencies and skill mix of the PHC workforce are defined in relation to the needs of the local population.

Learn more in the adjustment to population health needs & population health management modules.

- Purchasing and payment systems & funding and allocation of resources

-

Payment systems, as well as changes to spending on PHC as a whole, can impact the acquisition and retention of the PHC Workforce. However, it is not necessary that this alone would impact this input.

Learn more in the purchasing and payment systems & funding and allocation of resources modules.

- Physical infrastructure and medicines & supplies

-

The PHC workforce must be supported by adequate inputs, including physical infrastructure and medicines and supplies, in order to effectively carry out their duties. Without the necessary inputs, the ability of the PHC workforce to deliver high-quality care suffers.

Learn more in the physical infrastructure & medicines and supplies modules.

- Information & technology

-

Information systems enable the collection of robust workforce-related data for continued HRH strengthening.

Learn more in the information & technology module.

- Resilient facilities & services

-

Assessments of resilience in service preparedness can help identify vulnerabilities in the PHC workforce and work to help strengthen identified weak points, including the potential for workforce shortages during health emergencies.

Learn more in the resilient facilities & services module.

- Management of services

-

Management of funding is necessary to ensure facilities are sufficiently resourced to ensure safe working conditions for the PHC workforce and that the workforce is appropriately remunerated. In addition, quality assurance mechanisms that span from education to practice are important in ensuring that the PHC workforce is equipped with and demonstrates the knowledge and skills needed to deliver high-quality PHC services.

Learn more in the management of services module.

- Service availability & readiness

-

Provider availability, competency, and motivation are complementary mechanisms for improving the health workforce.

Learn more in the service availability & readiness module.

- Primary care functions

-

The high quality primary health care concept of comprehensiveness is important to reinforce as a strategy in HRH development such that the workforce is able to address a broad set of needs for a patient. People-centeredness and coordination are both important to reinforce in HRH development to ensure the existence of person-centeredness at the service delivery level as well as coordination of services across health-worker types.

Learn more in the primary care functions module.

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Countries seeking to improve their health workforce can pursue a wide array of potential improvement pathways. The short case studies below highlight promising and innovative approaches that countries around the world have taken to improve.

PHCPI-authored cases were developed via an examination of the existing literature. Some also feature key learnings from in-country experts.

- East Asia & the Pacific

- Europe & Central Asia

- Latin America & the Caribbean

- Middle East & North Africa

- North America

- South Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- Multiple regions

-

- Multiple countries: case studies on workforce assessments

- Multiple countries: health workforce country profiles

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Building consensus on what a strong health workforce is and key strategies to fix gaps is an important step in the improvement process.

Below, we define some of the characteristics of a strong health workforce in greater detail:

-

An effective PHC workforce is available and accessible to the population. This means that the population can access a health worker(s) regardless of location, time, or institution. Health worker and distribution indicators are critical starting points for understanding the accessibility and availability of the health workforce in a country. It involves looking at existing staffing and ratios as well as full-time equivalent posts compared to service demand. 48 However, it is also important to take into consideration whether providers meet the needs and preferences of the population and deliver high-quality care (discussed in the next dropdown). 8

Provider availability Provider availability is defined as the presence of a trained provider at a facility or in the community when expected to provide the services as defined by his or her job description. is also discussed in the service availability and readiness module. Accessibility and timeliness from the patient perspective are discussed in the access and service quality modules.

-

An effective workforce has the needed to meet the needs of the population. They are also organized--referred to as “composition” in a way that maximizes their performance:

- PHC competencies are the observable abilities--including knowledge, skills, and behaviours--of individual health workers that relate to specific work activities. Competencies The observable abilities—including knowledge, skills, and behaviours—of individual health workers that relate to specific work activities. Competencies are durable, trainable, and measurable. are durable, trainable, and measurable. 610 All members of the PHC workforce should have competencies related to people-centeredness, communication, decision-making, collaboration, evidence-informed practice, and personal conduct to enable them to provide comprehensive PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. which meet the majority of people’s needs. 810 Competencies The observable abilities—including knowledge, skills, and behaviours—of individual health workers that relate to specific work activities. Competencies are durable, trainable, and measurable. should be evidence-based and adapted to the country context to reflect the list of interventions at the PHC level and the structure of the PHC workforce in-country. 61016192021 Standards for workforce education, training, and practice should be based on these defined competencies and instituted for all occupations of the PHC workforce. Many different competency frameworks exist that are evidence-based. However, in order to ensure that these competencies are relevant to the country-specific package of PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. , to the way in which health care providers are organized and their scopes of work defined, it is essential that countries adapt evidence-based competencies to their context.

- Composition refers to the number, distribution, and of the PHC workforce, where skill mix describes the combination of different occupations of health workers delivering PHC in terms of numbers, diversity, and competencies. 11 PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. are best provided by coordinated, multidisciplinary teams with the wide range of knowledge, skills, and expertise needed to provide comprehensive, holistic care that is accessible and acceptable to the local community. 12131415 The different occupations of providers that make up a country’s PHC workforce may include family medicine doctors, nurses, midwives, , physician assistants, social workers, or others depending on the local context. The optimal skill mix of the PHC workforce will depend on the needs of the population and the best way to meet those needs within the context of the health system. 4101113151617 Some occupations of health workers, such as family medicine providers and some designations of general practitioners, are specifically trained in PHC and some countries have found having an approved medical speciality dedicated to comprehensive PHC to be a valuable and effective strategy. 1718 Additionally, integrating a diverse range of occupations, including mid-range and/or community-based workers, can help to support the realization of a diverse, sustainable workforce with the skills and reach needed to meet a comprehensive set of population health needs. 319 For example, given that PHC is often delivered in both communities and facilities, community-based health care workers may be integrated into the workforce plan to support proactive population outreach. 220

-

Building an efficient and effective PHC workforce in practice relies on strong in-country capacity (systems, evidence, policies, and investments) to implement, assess, and improve effective strategies and policies for PHC workforce education, recruitment and deployment, retention, and and regulation. 3

-

- Accreditation Accreditation [of a training institution or program] is a form of quality assurance in which a training institution or program is assessed to determine whether it meets predetermined and agreed-upon standards. If so, the institution or program is given accredited status. [of a training institution or program]: Accreditation Accreditation [of a training institution or program] is a form of quality assurance in which a training institution or program is assessed to determine whether it meets predetermined and agreed-upon standards. If so, the institution or program is given accredited status. is a form of quality assurance in which a training institution or program is assessed to determine whether it meets predetermined and agreed-upon standards. If so, the institution or program is given accredited status. 22

- Certification Certification [of a process or occupation] is, “the process whereby a profession or occupation voluntarily establishes competency standards for itself.” It is particularly useful in cases where the government has not regulated the profession or occupation through licensure. [of a profession or occupation]: Certification Certification [of a process or occupation] is, “the process whereby a profession or occupation voluntarily establishes competency standards for itself.” It is particularly useful in cases where the government has not regulated the profession or occupation through licensure. is, “the process whereby a profession or occupation voluntarily establishes competency standards for itself.” It is particularly useful in cases where the government has not regulated the profession or occupation through licensure. 22

- Community Health Workers Community health workers are a type of community-based health worker whose primary responsibility is to conduct proactive outreach in the community to meet local population health needs. : Community health workers are a type of community-based health worker whose primary responsibility is to conduct proactive outreach in the community to meet local population health needs. 13

- Competencies The observable abilities—including knowledge, skills, and behaviours—of individual health workers that relate to specific work activities. Competencies are durable, trainable, and measurable. : “ Competencies The observable abilities—including knowledge, skills, and behaviours—of individual health workers that relate to specific work activities. Competencies are durable, trainable, and measurable. are the observable abilities of individual health workers relating to specified activities of work that integrate knowledge, skills, and behaviours. Competencies The observable abilities—including knowledge, skills, and behaviours—of individual health workers that relate to specific work activities. Competencies are durable, trainable, and measurable. are durable, trainable and measurable.” 6

- Density Density [of the skilled workforce] is measured as the ratio of active health workers per population in the given national and/or subnational area. [of the skilled workforce]: Density Density [of the skilled workforce] is measured as the ratio of active health workers per population in the given national and/or subnational area. is measured as the ratio of active skilled health professionals to the total population. The World Health Organization has defined a required density of doctors, nurses, and midwives for meeting basic health needs and for achieving high coverage across the broad range of services that are targeted by universal health coverage as > 44.5 per 10,000 population. 35

- Incentives Incentives refer to, “a particular form of payment which is intended to achieve some specific change in behaviour. Incentives come in a variety of forms, and can be either monetary or non-monetary.” : Incentives Incentives refer to, “a particular form of payment which is intended to achieve some specific change in behaviour. Incentives come in a variety of forms, and can be either monetary or non-monetary.” refer to, “a particular form of payment which is intended to achieve some specific change in behaviour. Incentives Incentives refer to, “a particular form of payment which is intended to achieve some specific change in behaviour. Incentives come in a variety of forms, and can be either monetary or non-monetary.” come in a variety of forms, and can be either monetary or non-monetary.” 23

- Licensure Licensure (of an individual health worker) is a process in which a governmental authority determines the competency of an individual health worker seeking to perform certain services and grants that individual the authority to engage in a specific area(s) of practice based on demonstrated education, experience, and examination. Licensure also typically means that governments have the authority to discipline licensees who fail to comply with statutes and regulations as well as to take disciplinary action against unlicensed individuals who practice within the scope of a licensed profession or occupation. [of an individual health worker]: Licensure Licensure (of an individual health worker) is a process in which a governmental authority determines the competency of an individual health worker seeking to perform certain services and grants that individual the authority to engage in a specific area(s) of practice based on demonstrated education, experience, and examination. Licensure also typically means that governments have the authority to discipline licensees who fail to comply with statutes and regulations as well as to take disciplinary action against unlicensed individuals who practice within the scope of a licensed profession or occupation. is a process in which a governmental authority determines the competency of an individual health worker seeking to perform certain services and grants that individual the authority to engage in a specific area(s) of practice based on demonstrated education, experience, and examination. Licensure Licensure (of an individual health worker) is a process in which a governmental authority determines the competency of an individual health worker seeking to perform certain services and grants that individual the authority to engage in a specific area(s) of practice based on demonstrated education, experience, and examination. Licensure also typically means that governments have the authority to discipline licensees who fail to comply with statutes and regulations as well as to take disciplinary action against unlicensed individuals who practice within the scope of a licensed profession or occupation. also typically means that governments have the authority to discipline licensees who fail to comply with statutes and regulations as well as to take disciplinary action against unlicensed individuals who practice within the scope of a licensed profession or occupation. 22

- Posting and transfer Posting and transfer refers to geographic deployment of health workers. It encompasses both initial health worker posting and subsequent transfers of staff between health facilities. : Posting and transfer Posting and transfer refers to geographic deployment of health workers. It encompasses both initial health worker posting and subsequent transfers of staff between health facilities. refers to the geographic deployment of health workers. It encompasses both initial health worker posting and subsequent transfers of staff between health facilities. 2425

- Quality assurance Quality assurance of the health workforce refers to systems for ensuring that the practicing primary health care workforce has the appropriate training and qualifications, that lists of those appropriately trained and qualified providers are maintained, and that appropriate measures are taken with respect to providers who do not meet established standards. : Quality assurance Quality assurance of the health workforce refers to systems for ensuring that the practicing primary health care workforce has the appropriate training and qualifications, that lists of those appropriately trained and qualified providers are maintained, and that appropriate measures are taken with respect to providers who do not meet established standards. of the health workforce refers to systems for ensuring that the practising primary health care workforce has the appropriate training and qualifications, that lists of those appropriately trained and qualified providers are maintained, and that appropriate measures are taken with respect to providers who do not meet established standards. 10

- Remuneration Remuneration is traditionally seen as the total income of an individual that may take different forms, such as salary, stipend, honorarium, and/or monetary incentives. A remuneration strategy determines this particular configuration or bundling of payments that make up an individual’s total income. The World Health Organization recommends that all occupations of the health workforce be remunerated with a financial package in accordance with the employment status and applicable laws and regulations in the jurisdiction. : Remuneration Remuneration is traditionally seen as the total income of an individual that may take different forms, such as salary, stipend, honorarium, and/or monetary incentives. A remuneration strategy determines this particular configuration or bundling of payments that make up an individual’s total income. The World Health Organization recommends that all occupations of the health workforce be remunerated with a financial package in accordance with the employment status and applicable laws and regulations in the jurisdiction. is traditionally seen as the total income of an individual that may take different forms, such as salary, stipend, honorarium, and/or monetary . A remuneration strategy determines this particular configuration or bundling of payments that make up an individual’s total income. The World Health Organization recommends that all occupations of the health workforce be remunerated with a financial package in accordance with the employment status and applicable laws and regulations in the jurisdiction. 31323

- Skill mix Skill mix describes the combination of different occupations of health workers (i.e. doctors, nurses, and midwives) in a primary care practice in terms of numbers, diversity, and competencies. : Skill mix Skill mix describes the combination of different occupations of health workers (i.e. doctors, nurses, and midwives) in a primary care practice in terms of numbers, diversity, and competencies. describes the combination of different occupations of health workers (i.e. doctors, nurses, and midwives) in a primary care practice in terms of numbers, diversity, and competencies. 26

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

References:

- WHO. Building the primary health care workforce of the 21st century: a technical series on primary health care. World Health Organization. 2018;

- WHO. Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: A handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. World Health Organization; 2010.

- WHO. Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. 2016;

- World Health Organization. 2. Health Workforce. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. 2010. p. 24–42.

- World Health Organization. Working Together for Health: The World Health Report. 2006.

- World Health Organization. March 2019 Working Draft of the Global Competency Framework for Universal Health Coverage. World Health Organization; 2019 Mar.

- HRH2030 Program | Increase Number, Skill Mix, and Competency of the Health Workforce [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 19]. Available from: https://hrh2030program.org/increase-number-skill-mix-and-competency-of-the-health-workforc/

- WHO. Building the primary health care workforce of the 21st century: a technical series on primary health care. World Health Organization; 2018.

- WHO. Primary Health Care Transforming Vision into Action: Operational Framework. World Health Organization; 2018.

- PHCPI. Primary Health Care Progression Model Assessment Tool [Internet]. Primary Health Care Progression Model Assessment Tool. 2019. Available from: https://improvingphc.org/sites/default/files/PHC-Progression%20Model%202019-04-04_FINAL.pdf

- HRH2030 Program | Increase Health Workforce Performance and Productivity [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 19]. Available from: http://hrh2030program.org/increase-health-workforce-performance-and-productivity/

- WHO. Transforming Vision into Action: Operational Framework for Primary Health Care. WHO; 2020 Dec.

- WHO. WHO guidelines on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- Garimella S, Sheikh K. Health worker posting and transfer at primary level in Tamil Nadu: Governance of a complex health system function. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016 Sep;5(3):663–71.

- Mbemba GIC, Gagnon M-P, Hamelin-Brabant L. Factors influencing recruitment and retention of healthcare workers in rural and remote areas in developed and developing countries: an overview. J Public Health Africa. 2016 Dec 31;7(2):565.

- WHO & UNICEF. A Vision for Primary Health Care in the 21st Century: towards universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals. . World Health Organization; 2018.

- WHO. Working for Health and Growth - Investing in the health workforce. High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth, editor. WHO; 2016.

- WHO, OECD, The World Bank. Delivering quality health services: A global imperative for universal health coverage. Geneva: WHO, The World Bank, and OECD; 2018.

- Rao M, Pilot E. The missing link--the role of primary care in global health. Glob Health Action. 2014 Feb 13;7:23693.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Future of Primary Care. Defining primary care: an interim report. Donaldson M, Yordy K, Vanselow N, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1994.

- Starfield B. New paradigms for quality in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2001 Apr;51(465):303–9.

- WHO. Transforming and scaling up health professionals’ education and training. World Health Organization; 2013.

- World Health Organization. Health workforce incentive and remuneration strategies. World Health Organization. 2000;

- Schaaf M, Sheikh K, Freedman L, Juberg A. Chapter 16: a hidden human resources for health challenge: personnel posting and transfer. In: Health Employment and Economic Growth: An Evidence Base. Buchan J, Dhillon I, Campbell J, editors. World Health Organization; 2017.

- Heerdegen ACS, Bonenberger M, Aikins M, Schandorf P, Akweongo P, Wyss K. Health worker transfer processes within the public health sector in Ghana: a study of three districts in the Eastern Region. Hum Resour Health. 2019 Jun 24;17(1):45.

- Dubois C-A, Singh D. From staff-mix to skill-mix and beyond: towards a systemic approach to health workforce management. Hum Resour Health. 2009 Dec 19;7:87.