|

|

|

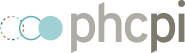

Service availability measures assess the extent to which specific services are offered and available in the relevant health care settings and readiness assesses whether facilities have the necessary staff, guidelines, equipment, diagnostics, medicines and commodities to deliver these services. Taken together, service availability and readiness is a measure of whether a patient, upon accessing care, encounters a provider and facility that are present, competent, and motivated to provide safe, high-quality, and respectful care that builds trust between providers and patients.

Service availability and readiness is closely linked to organisation of services. The manner in which the health system is organized and services are delineated across levels of care will determine what type of staff, competencies, and supplies are necessary at each facility to ensure that the facility is prepared to meet the services they are expected to provide. However, while the presence of well-trained providers is necessary for service availability, it is also crucial that they have the relevant competencies and are well supported and motivated to provide services.

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Before taking action, countries should first determine whether service availability & readiness is an appropriate area of focus and where to target improvement efforts. Read on to learn how to use country data to:

- Make informed decisions about where to spend time and resources

- Track progress and communicate these updates to constituents or funders

- Gain new insights into long-standing trends or surprising gaps

Countries can measure their performance using the Vital Signs Profile (VSP). The VSP is a first-of-its-kind tool that helps stakeholders quickly diagnose the main strengths and weaknesses of primary health care in their country in a rigorous, standardized way. The second-generation Vital Signs Profile measures the essential elements of PHC across three main pillars: Capacity, Performance, and Impact. Service availability & readiness is measured in the Management of services & population health domain of the VSP (Capacity Pillar).

If a country does not have a VSP, it can begin to focus improvement efforts using the subsections below, which address:

- Key indications

-

If your country does not have a VSP, the indications below may help you to start to identify whether service availability & readiness is a relevant area for improvement:

- High bypass and utilization of higher levels of care: Patients may bypass primary health care services for a variety of reasons, including poor service availability. If patients are unable to see providers in a timely way and/or be met with the kind of care they need, they will likely seek care at a higher-level facility, bypassing the primary care level.

- Low patient satisfaction with care: Patients may be dissatisfied with their care if they are not cared for by competent and motivated providers.

- Fragmented care: If facilities are unable to provide the services that they are expected to provide, they may need to refer patients elsewhere, making patient care more fragmented and less continuous.

- Low provider retention and high absenteeism: If providers are not adequately trained to provide the services they are expected to deliver or if they are overworked, there may be low provider retention and high absenteeism. Ensuring that there are a sufficient number of providers to manage the patient population, providing them with adequate compensation, and ensuring that they have the relevant training may help.

- Key outcomes and impact

-

Countries that improve service availability & readiness may achieve the following benefits or outcomes:

- First contact accessibility & trust: By ensuring that services are easily available to patients and that providers are competent and motivated, patients will find primary health care services more acceptable and trustworthy and seek primary health care as the first point of contact with the health system.

- Less care fragmentation and better outcomes: When primary health care settings are equipped with an adequate number of competent providers and have access to necessary resources, 95% of patient contact with the health systems should be able to take place in primary care settings with only 5% of patients being referred to secondary care (1).

- Safety and effectiveness: Competent and available health care providers who have access to the necessary drugs and supplies will be better equipped to deliver effective, evidence-based care to patients.

- Timely, person-centred, high-quality care: When providers are available, competent, and motivated and have access to the necessary resources to carry out their scope of work, services will be more timely, person-centred, and high-quality.

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Explore this section for a curated list of actions that countries can take to improve service availability & readiness in their context, which embark on:

- Explaining why the action is important for service availability & readiness

- Describing activities/ interventions countries can implement to improve

- Describing the key drivers in the health system that should be improved to maximize the success/impact of actions

- Curating relevant case studies, tools, &/or resources that showcase what other countries around the world are doing to improve as well as select tools and resources.

Key actions:

-

There are a number of different assessment tools that can be used to understand service availability and readiness. These assessments may help illuminate gaps or areas of improvement at an individual health facility or national level and help initiate conversations about improvement plans. The information that comes from a facility assessment can also help support planning and ongoing management, monitoring, and evaluation.

Key activities

- Select and conduct a health facility assessment - Health facility assessments are conducted at the facility level and the first step is determining which assessment tool to use and who will administer it. There are a number of different health facility assessment tools, some of the larger ones are listed below under “relevant case studies, tools, and resources.” The individual or team that will be conducting the assessment should evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each assessment tool and compare those to their particular needs when selecting a tool. Some assessments may be run nationally or even internationally by groups such as the Demographic and Health Surveys Program or the World Health Organization, in which case individual facilities may not have much choice in which survey to use. For example, both the Service Provision Assessment (SPA) and the Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA), some of the most widely used, standardized facility assessment tools are implemented as a census or a nationally/sub-nationally representative sample of health facilities. 48

- Interpret the results of a health facility assessment - The way in which data from a health facility assessment is interpreted will depend upon the level at which it was administered. If larger, national-level surveys are used, individual facilities may not have access to their performance so the results would be more useful to policymakers. However, if a facility conducts its own health facility assessment, the data will be most useful to a facility manager who can use it to assess where and how the facility can improve readiness.

Related elements

Relevant tools & resources

- Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA) - The SARA methodology was developed through a joint World Health Organization and United States Agency for International Development collaboration. It focuses on the availability of human and infrastructure resources as well as the availability of basic equipment, amenities, essential medicines, diagnostic capacities, and the readiness of facilities to provide basic health care interventions.

- The Service Provision Assessment (SPA) - The SPA was developed by the Demographic and Health Surveys Program and is a nationwide facility-based survey using inventory, dynamic observation of services, exit interviews, and health worker interviews. SPA is typically implemented by the Ministry of Health with assistance from the National Statistical Institute. More information on SPA can be found here.

- Service Delivery Indicators (SDI) - The SDI health surveys are nationally representative facility-based surveys developed by The World Bank Group. They assess quality and performance from the citizen’s perspective.

- The Harmonized Health Facility Assessment (HHFA) - The HHFA assesses the availability of health facility services and capacities to provide services at required standards of quality. It builds upon SARA and other health facility survey tools. The HHFA includes four modules on service availability, service readiness, quality of care, and management and finance.

- Data portal on noncommunicable diseases, mental health, and external causes - this data portal from PAHO provides indicators relevant to technical programs related to noncommunicable diseases, violence, injuries, risk factors for noncommunicable diseases, nutrition and physical activity, mental health, substance use prevention, and disability and rehabilitation

-

The presence of staff who are able to provide the services expected at a given facility is a critical component of service availability and readiness. Without sufficient staff, patients may bypass facilities or delay treatment.

Key activities

Health systems level

- Policies and recruitment strategies are in place for providers - ensuring an adequate supply of providers that are appropriately distributed by geography, cadre, and according to demographic or social determinants as well as need is most often addressed at the national or subnational level. This may be done through policies and other strategies that encourage people to become health workers and provide them with adequate and financially accessible education. Depending on the context, countries may consider special incentives for rural work or for certain specialities such as primary care of family medicine.

- Expand roles and responsibilities of underutilized providers - many providers may have the potential to take on additional responsibilities to balance workload. For example, midwives are often trained to provide far more services than what is included in their typical scope. Health systems may consider shifting some responsibilities to under-utilized staff to ensure that other staff can focus their efforts elsewhere. It is important to note that any change in responsibilities should be accompanied by training and additional remuneration.

District &/or facility level

- Take steps to reduce absenteeism - absenteeism is when providers do not show up for their scheduled shifts and is quite common in low- and middle-income countries. 16 Absences may be due to personal factors or for work-related reasons such as a challenging work environment, lack of motivation, or a need to supplement their income elsewhere. Motivational incentives such as performance-based financing, supportive supervision, appropriate autonomy, systematic recognition, and professional development may help in improving motivation.

Related elements

- Policy & leadership

- Purchasing & payment systems

- PHC workforce

- Population health management

- Management of services

Relevant tools & resources

- Global Strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030 – This guideline was created through a consultative process and suggests objectives for the health workforce in the coming decades

- WHO guidelines on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programmes – while this guideline is specific to community health workers, elements are relevant to any community-based provider. The guideline is informed by systematic reviews of the literature.

- Quality improvement the action of every person working to implement iterative, measurable changes, to make health services more effective, safe, and people-centred. in practice - part two: applying the joy in work - the four case studies in this article demonstrate the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s “joy in work” framework. This framework could be a valuable tool for improving staff motivation and satisfaction.

- Performance management in complex adaptive systems: a conceptual framework for health systems - this framework identifies factors that can create a balance between directive and enabling approaches to performance management and ultimately improve performance monitoring and incentives.

- Managing for motivation as a public performance improvement strategy in education and far beyond - this paper from Harvard University discusses different strategies for people management. While the paper focuses on education systems, it is also relevant to the health system.

- Building better together: a roadmap to guide implementation of the Global Strategic Directions for Nursing and Midwifery in the WHO European Region - This roadmap provides activities for education, jobs, leadership, and service delivery related to nursing and midwifery

-

In addition to being physically available to provide services, providers must have the necessary skills and training to safely deliver care. If patients do not perceive care to be high-quality and safe, they may delay seeking care or bypass primary care settings.

Key activities

Health systems level

- Provide high-quality pre-service education and training - Institutions and policies for health education and training should be nimble enough to respond to local human resource needs. Collaboration with Ministries of Education can help to ensure that primary and secondary schools prioritize science education to prepare students to continue into health professional education. Among other things, curricula should be competency-based, harness global resources but adapt them locally, and use competencies as a criterion for the classification of professionals. 26

- Offer continued professional development - continuing professional development is an important opportunity to keep providers’ technical skills refreshed and updated. It typically includes certification or recertification. While continuing professional development guidelines and requirements may be established at the health system level, it’s best for it to be delivered in the facility to improve access for providers. Most countries will have a regulatory board for each cadre and incorporating professional development requirements into these regulatory board frameworks may improve opportunities for professional development and ensure accountability.

District &/or facility level

- Provide ongoing training - Frequent and ongoing in-service training in addition to pre-service training is important for ensuring that health care workers refresh their skills. This is especially important if scopes of work are expanded to ensure that health workers are licensed to deliver their assigned tasks safely. Training for community-based providers may occur on the district or facility level as well. The specific proficiencies that are needed for community-based providers will depend on the structure of the health system and the specific services that are expected to be provided in the community.

- Ensure that staff receive supportive supervision - Supportive supervision is an approach where supervisors focus on joint problem solving and strengthening relationships with staff rather than high-level problem-solving. While non-supportive supervision focuses on inspection and line management, supportive supervision focuses on building pathways to improvement through active collaboration between providers and supervisors. 49 Supportive supervision is most successful when there is two-way communication between providers and supervisors with real-time feedback, non-judgemental approaches that focus on active listening and humility, and cordial relationships. Supervisors should be trained on how to coach, mentor, communicate, and conduct performance planning.

- Provide access to and training on protocol-based approaches to care - There are a number of protocol-based approaches and decision-making tools that can be used to improve the technical quality of care. Many of these can be administered in communities and homes as well as in facilities. We include links to three such tools in “case studies, resources, and tools” below.

Related elements

Relevant tools & resources

- Global Strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030 – This guideline was created through a consultative process and suggests objectives for the health workforce in the coming decades

- Protocol-based approaches include: Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI); Integrated Management of Adolescent Illness (IMAI); Package of Essential Non-Communicable Disease Interventions (PEN)

- Health literacy training - The CDC has put together training in health literacy, plain language, and culture and communication for anyone working in health information and services. They have also put together a list of health literacy training from organizations other than the CDC

- Guide for the development of occupational health and safety programmes for health workers - this guide can be used to provide an overview of preventing disease and injuries that arise out of, are linked with, or occur in the course of work

- Global competency framework for universal health coverage - the WHO’s global competency framework focuses on six domains of UHC and has been developed through the lens of 12-48 month pre-service education pathways.

-

Even with the presence of an available, competent, and motivated health workforce, facilities will not be able to adequately serve patients if they don’t have access to the medicines and supplies necessary to treat their conditions.

Key activities

Health systems level

- Reference existing guidelines on the essential package of health services and levels of care - A first step for understanding what drugs and supplies are necessary at each level of care and care delivery site is consulting the essential package of health services and guidelines on each level of care. These are discussed in more detail in the organisation of services. Both across and within countries, not all facilities will require access to the same drugs and supplies and these guidelines will detail the responsibilities of each facility and the types of conditions they should be able to treat.

- Ensure systems for supply chain management - The supply chain refers to the resources needed to deliver goods or services to a consumer. Supply chain management Supply chain management encompasses the planning and management of all activities involved in sourcing and procurement…and all logistics management activities. Importantly, it also includes coordination and collaboration with channel partners, which can be suppliers, intermediaries, third party service providers, and customers. In essence, supply chain management integrates supply and demand management within and across companies. includes obtaining resources, managing supplies, and delivering goods and services to providers and patients. Activities involved in supply chain management include product consumption tracking, product selection, quantification, procurement, inventory control policies, and warehousing & distribution. More detail on supply chain management can be found in medicines and supplies.

- Ensure quality, safety, and efficacy of health products - The following four levers are important for ensuring quality, safety, and efficacy of health products: regulatory system strengthening, assessment of the quality, safety, and efficacy/performance of health products through prequalifications, and market surveillance and assessment of quality, safety, and performance. Each is discussed in greater detail in medicines and supplies.

Related elements

- Policy & leadership

- Information & technology

- Purchasing & payment systems

- Funding & allocation of resources

- Medicines & supplies

- Management of services

Relevant tools & resources

- JSI: The supply chain manager’s handbook: a practical guide to the management of health commodities

- USAID: Optimizing supply chains for improved performance

- WHO: Promising practices in supply chain management

- WHO: Draft road map for access to medicines, vaccines, and other health products, 2019-2023

- WHO: WHO Model List of Essential Medicines

-

Infection prevention and control is necessary at all facilities to ensure the safety of patients and providers, regardless of the type of services provided at that site.

Key activities

National level

- Establishment of a national IPC program - National IPC programs should have clear objectives, functions, appointed infection preventionists, and a defined scope of responsibilities. Objectives should include goals for endemic and epidemic infections and the development of recommendations for IPC processes and practices. 46

- Provide support for education and training - develop pre-graduate and postgraduate IPC curricula and guidance for in-service training at the facility level.

- Establish national surveillance programs - national surveillance programs and networks should have mechanisms for timely data feedback.

Facility level

- Adapt national IPC guidelines - adaptation to local conditions will make the uptake of national guidelines most effective.

- Implement IPC education and training - this should be part of new employee education as well as continuing education. Training should be available to IPC specialists, all health care workers involved in service delivery, and other personnel that support health service delivery.

- Implement health care-associated infection surveillance - surveillance should be informed by national recommendations and provide information on the status of infections, identification of relevant antimicrobial resistance patterns, high-risk populations, functioning of WASH infrastructure, early warning systems, and evaluation of the impact of interventions.

- Ensure appropriate workload, staffing and bed occupancy - in order to maintain a safe working environment in acute health care facilities, facility managers should ensure that bed occupancy not exceed the standard capacity of the facility and that health care worker staffing levels are adequately assigned.

Related elements

Relevant tools & resources

- Infection prevention and control at the facility level assessment - This assessment can be used to understand the current functioning and capacity of IPC measures at a facility

- Guidelines on core components of infection prevention and control programmes at the national and acute health care facility level

- Minimum requirements for infection prevention and control programmes

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Understanding and identifying the drivers of health systems performance--referred to here as “related elements”--is an integral part of improvement efforts. We define related elements as the factors in a health system that have the potential to impact, whether positive or negative, service availability & readiness. Explore this section to learn about the different elements in a health system that should be improved or prioritized to maximize the success of actions described in the “take action” section.

While there are many complex factors in a health system that can impact service quality, some of the major drivers are listed below. To aid in the prioritization process, we group the ‘related elements’ into:

Upstream elements

We define “upstream elements” as the factors in a health system that have the potential to make the biggest impact, whether positive or negative, on service availability & readiness.

- Organisation of services

-

As discussed in the deep dive section, the organisation of services includes establishing an essential package of health services, delineating what services are delivered at each level of care, and establishing care pathways for tracer conditions. Without these in place, it may be difficult for a health system to determine what constitutes readiness at a given facility.

- Policy & leadership

-

Primary health care policies should define the scope of services provided by primary health care and different PHC facilities types to guide the measurement of readiness and service availability. Additionally, national guidelines related to infection control and prevention as well as feedback mechanisms are crucial for ensuring service readiness.

- Physical Infrastructure, medicines, & supplies

-

An important aspect of service availability and readiness is the presence of well-maintained facilities with an adequate supply of the right medicines and supplies necessary to deliver services. Adequate supply chains and systems for procurement must be in place to support this.

Learn more in the physical infrastructure and medicines & supplies modules.

- Health workforce

-

Available, competent, and motivated health care workers must be present at facilities for patients to have access to care. Therefore, there must be a sufficiently sized PHC workforce with standardized educational requirements in the country.

- Management of services

-

Effective facility management and performance measurement and management is essential for ensuring that both inputs and workforce are ready and available and that guidelines are being adhered to, monitored, and reported on.

- Safety

-

Poor safety protocols may result in lower availability and motivation of providers.

Complementary elements

We define “complementary elements” as the factors in a health system that have the potential to make an impact, whether positive or negative, on service quality. However, we consider these drivers as complementary to, but not essential to performance.

- Purchasing and payment systems

-

To ensure the readiness of services, there must be adequate means of procuring necessary medicines and supplies.

- Information & technology

-

Information systems can assist with timely remuneration of staff which can help to improve retention and motivation of health care workers.

- Population health management

-

An important element of population health management is the presence of appropriately sized patient panels. This can help prevent overburdening providers and ensure that they have adequate time to devote to patients, preventing burnout and improving satisfaction.

- People-centred care

-

Organizing care around patient needs and engaging patients as partners in their care supports mutual respect and trust and may improve the experience of health care providers.

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Countries seeking to improve service availability & readiness can pursue a wide array of potential improvement pathways. The short case studies below highlight promising and innovative approaches that countries around the world have taken to improve.

PHCPI-authored cases were developed via an examination of the existing literature. Some also feature key learnings from in-country experts.

- East Asia & the Pacific

-

- Indonesia: Puskesmas and the Road to Equity and Access

- Europe & Central Asia

-

- Estonia: Retraining and incentivizing providers to deliver high-quality PHC

- Portugal: Strengthening the delivery of integrated, continuous care across levels of care through the Portuguese National Network for Integrated Continuous Care

- Turkey: Greater availability of PHC services results in high patient and physician satisfaction

- Latin America & the Caribbean

- Middle East & North Africa

- North America

- South Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

-

- Rwanda: Enhancing mentoring and supervision to improve quality of services

- Tanzania: Increasing efficiency and equality in the pharmaceutical supply chain through the single system for managing medicines and medical supplies

- Tanzania: Increasing provider competency through mobile-based decision-making tools

- Uganda and Rwanda: Addressing absenteeism through performance-based financing

- Multiple regions

-

- Thailand, Costa Rica, Estonia: Improving provider motivation using monetary incentives

- Multiple countries: Measuring provider motivation and satisfaction

- Multiple countries: Improving provider availability through facility infrastructure and workforce strengthening

- Multiple countries: Improving service delivery through shared medical appointment models

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Building consensus on what service availability & readiness is and key strategies to fix gaps is an important step in the improvement process.

Below, we define some of the core characteristics of service availability & readiness in greater detail:

-

Provider availability Provider availability is defined as the presence of a trained provider at a facility or in the community when expected to provide the services as defined by his or her job description. is defined as the presence of trained providers at a facility or in the community when expected who competently provide the services as defined by their job description. Availability is important because, while there are often shortages in human resources, deployed providers are frequently inappropriately absent or, when present, are not actively delivering health care because they are engaged in other duties.

There are three components of provider availability that affect how and when patients are able to receive services from competent providers:

- First, there must be an adequate supply of providers competent in comprehensive primary care who are appropriately distributed by geography, cadre, and according to demographics or social determinants as well as needs. Provider supply is most often addressed at the national or subnational level through policies and recruitment strategies as well as through decentralizing education programs and expanding rural health training.

- Second, once trained providers are present and deployed, they must show up for work when they are scheduled. Not being present during scheduled shifts is frequently referred to as absenteeism. Interventions to improve absenteeism span many levels of the health system.

- Finally, even when competent providers are present for their planned shifts, their work must be structured in such a way that they have an appropriate amount of time to spend with patients and are able to communicate with each other between shifts or during transitions. Improvements in provider consultation time are most often pursued at the facility level.

Presence & distribution of providers

In light of global attention on the achievement of Universal Health Coverage by 2030 as described in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),(2) many international organizations have focused on the global availability of human resources. The WHO has developed a global strategy on human resources for health for planners and policy-makers, informed by a multi-year consultation process. The document is framed around four objectives and global milestones for both 2020 and 2030 to measure progress. The global strategy provides policy options for countries in each of the four objectives. 3 These global and national strategies relevant to human resources for health will be discussed in greater detail in health workforce, though we present a few relevant considerations here.

Improving workforce in rural areas

Strategies to recruit, retain, and station providers – commonly called Posting and Transfer (P&T) - include:

- Expanding education and capacity targeted at specific cadres or regions in order to train and deploy more qualified providers;

- Providing core training closer to the service environment as well as greater continuing education and professional development opportunities locally;

- Strengthening primary and pre-service training programs in existing institutions in areas where there is an inadequate supply;

- Providing incentives and support for providers working in rural areas;

- Instituting mandatory civil service in rural areas; and

- Developing methods for improving provider motivation and satisfaction such as supportive supervision, access to career development and continuing education, ensuring an adequate workload, providing psychosocial support, and improving facility infrastructure so as to promote provider retention. 34567

The WHO has developed a set of strategies to improve the recruitment and retention of health workers in rural areas. The document addresses: national policies to improve retention; recommendations for improving attraction, recruitment, and retention related to education, incentives, and professional support; suggestions for evaluation of rural retention; and research gaps and agendas. 8

Workforce optimization and roles & responsibilities

The WHO Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030 focuses on workforce optimization and roles and responsibilities. Often, the skills of providers are underutilized, and access to high-quality care could be improved by better matching tasks and responsibilities to provider competencies. For instance, midwives have the potential to provide nearly 90% of care for sexual, reproductive, maternal, and newborn services, but often their scope is significantly more limited. By expanding roles and responsibilities with adequate training, incentives, remuneration, and supervision, facilities may strengthen the availability and readiness of these specific services. 3

A similar strategy used to strengthen the availability of competent providers is optimizing the skill mix of providers. Often called task shifting, this entails moving responsibilities from one type of health worker to another who may have less specific training but still has the competencies to deliver the given service. 9 Often, optimizing the workforce by shifting responsibilities to cadres that are in greater supply can be an effective strategy for increasing capacity and improving provider availability, ultimately improving patient access to high-quality care. Optimizing responsibilities within an adequately staffed team can allow a team of health care workers each with an individually narrower range of skills to provide the more comprehensive approach required in primary care. Successful task shifting has been demonstrated extensively for HIV and maternal health services in low and middle-income countries, and growing evidence suggests that it may be a suitable approach for managing the growing burden of non-communicable diseases in these settings as well. 101112

However, it is crucial to ensure that providers who gain responsibilities have adequate training in their new responsibilities to ensure that the health workforce is able to deliver high-quality and safe care. The following general steps should be taken to implement changing roles and responsibilities:

- Identify or inventory the existing skills within the workforce at the national, regional, district, and/or facility level.

- Identification of skills within the workforce or tasks within the facility that a certain cadre is either trained to do but not yet doing or could be trained to do.

- Conduct training to enable providers to deliver new skills.

- Support these providers with the necessary management support and infrastructure to carry out their new tasks.

- Involve communities throughout to ensure the acceptability of services and providers.

Health workers in the private sector

Health workers in the private sector make up a significant portion of the health workforce in many countries. 1314 The private sector includes providers working at either “formal” and “informal” health institutions, with the former including legally recognized for-profit and not-for-profit organizations and the latter comprising non-legally recognized individuals such as informal drug sellers, shop keepers, and lay health workers. The size of the private health workforce, its regulation and credentialing, and the population’s access to these providers can all affect overall provider availability. Particularly in the informal sector, there is often little quality regulation of health workers in the private sector, and private sector institutions and health workers differ significantly in training and scope between and within countries. 13 While there is increasing attention to and research on the regulation of the formal private sector, there is limited literature or normative guidance on the informal sector. Often, strategies intended to improve quality or availability of primary care services focus exclusively on the public sector, overlooking a major source of care for a significant portion of the population.

A systematic review of the literature comparing quality of care between formal public and private providers found 80 quantitative analyses and two qualitative ones, primarily from Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia and the Pacific. 13 The review found that structure, competence, and clinical practice were relatively similar between the public and private sector, and both were quite poor with a computed median quality score – a summary of structural, delivery, and technical quality – of 50/100. However, the formal private sector had slightly better drug availability, responsiveness, and effort, perhaps due to more flexible use of funds.

Often, it is the competence of both public and private providers – not availability – that prevents improvements in health status. For instance, a study in the poor, rural state of Madhya Pradesh, India, found that on average, a household had access to more than five medical providers in their village, but 67% of these had no medical training. 15 One of the goals outlined in the WHO’s Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030 is “by 2020, all countries will have a regulatory mechanism to promote patient safety and adequate oversight of the private sector,” highlighting the global importance of private sector regulation. 3 Policy options and recommendations relevant to this goal can be found in the document. Thus, understanding the variation in both public and private provider availability, competence, regulation, and utilization is a crucial first step when designing interventions to strengthen the health workforce.

Absenteeism

Unplanned absenteeism - defined as when providers do not show up for their scheduled shifts - is a common barrier to effective care in low and middle-income countries (LMIC). Even with an adequate national or sub-national supply and distribution of health workers, they must be present in facilities in order to improve patient health. The Service Delivery Indicators survey fielded between 2012 and 2016 found absenteeism rates of 27.5% in Kenya, 27.4% in Madagascar, 33.1% in Niger, and 14.3% in Tanzania. 16 Despite these data only being available in select countries, absenteeism is a challenge in many LMICs. Unplanned absences might be due to personal factors such as illness, unexpected lack of childcare, or challenges with transportation. However, providers may also be absent for other reasons such as a challenging work environment, lack of motivation, participation in mandatory in-service training, or a need to supplement insufficient income through dual employment elsewhere. These latter factors are more amenable to health system interventions.

What drives absenteeism?

Particularly in public facilities in LMIC, there are often no sanctions for providers who are absent. For some providers, this lack of accountability translates to low motivation to attend work. Providers may even seek dual-pay by working in the private sector but receiving a paycheck for a job they do not attend or attend infrequently in the public sector. 17

USAID and CapacityPlus have developed a technical brief on governance issues that affect absenteeism. They identified 10 underlying issues: standards that are not transparent, insufficient supervision, ineffective supervision, poor working conditions, inadequate financial and non-financial incentives, delayed remuneration, lack of performance incentives, limited quality of data, insufficient political will, and few consequences. 18

Recognizing that the issue of absenteeism is influenced by diverse stakeholder groups, the brief also includes system-wide efforts that can be undertaken to reduce absenteeism for each of these underlying issues. Some of these strategies are discussed below.

Interventions

Basic health system inputs must be in place before health system stakeholders can focus on motivational factors to reduce absenteeism. These include access to necessary functional drugs and equipment, timely payment, access to communication and transportation, and a positive work environment free of intimidation or aggression. Assuming basic inputs of pay, environment, and safety, providing greater provider incentives may further reduce absenteeism. Motivational incentives include performance-based financing (PBF), supportive supervision, appropriate autonomy, systematic recognition and increased stature for those employed in primary care, and professional development. PBF or systems to track and monitor provider absences may help prevent dual practice and absenteeism. 19 However, both require significant information system infrastructure. Additionally, it is important to note that while there are perceived benefits associated with PBF, it can also create perverse incentives. This is discussed in greater detail in the provider motivation section below and in purchasing and payment systems.

Finally, when providers seek dual-pay outside of the public sector, it is likely an indication that they are not receiving appropriate remuneration from public facilities, and improved provider compensation should be prioritized to achieve greater competitiveness with salaries in the private sector. Formal recognition of primary care disciplines and qualifications similar to other medical disciplines and specialities can greatly enhance provider satisfaction, interest, and evaluation of self-worth. Supportive supervision and professional development are discussed in greater detail under provider motivation below. Other strategies for improving absenteeism include absence policies that are well distributed and communicated or mandatory interviews with providers who are frequently absent linked with organizational support and problem-solving. 20

Service delivery structures & timeliness

The third component of provider availability is determined by facility structure. Timeliness Timeliness refers to the ability of the health system to provide PHC services to patients when they need them with acceptable and reasonable wait times and at days and times that are convenient to them. is one important component of provider availability. Here, we consider timeliness to be the ability to access a competent provider for a sufficient amount of time at a time of the day and week that is convenient. Additionally, patients should not face substantial waiting times once in the facility. A more comprehensive discussion of timeliness is in the Access module.

Once patients are present at a facility, they may not be able to access a provider for a variety of reasons. If providers have a significant caseload, they may not be able to spend a sufficient amount of time with each patient. Part of the provider’s caseload may involve burdensome administrative tasks or other duties that take time away from patient encounters. Additionally, many facilities in LMIC do not have appointment systems thus resulting in long waiting times, particularly in the morning when clinics first open.

Timely availability of care is an important aspect of patient trust in the health system. If patients travel to a clinic and face long waiting times and short consultations, they may choose to bypass the first point of care, consult more readily available informal providers, or avoid care altogether for subsequent health needs.

Some strategies for improving the timely availability of providers within a facility include:- Adjusting responsibilities – If there is an adequate supply of human resources, moving responsibilities to different staff may help enable providers to spend more time with patients. The way in which responsibilities are divided among the health workforce depends on their training and competence and should always be done with optimization of roles in mind. 3 It is crucial to ensure that providers have the relevant competencies to carry out their responsibilities when optimizing roles and scopes of practice and that they are part of larger multidisciplinary teams that are structured to meet population health needs.

- Appointment systems – creating appointment systems can help increase clinic efficiency and reduce waiting times. However, there must be adequate communication and record-keeping capacity to implement an appointment system. Different options for appointment systems are discussed in more detail in the service quality module.

- Appropriately sized patient populations – When providers are overburdened by patient demand, they may not have adequate time to devote to each patient. This can be avoided during empanelment. When planners determine the appropriate size for each panel, provider burden and the number of available providers should be a primary consideration.

- Shared medical appointments or block appointments – shared medical appointments can decrease wait times and optimize provider time by pairing a group of patients with similar health needs with a single provider. Shared medical appointments have been used extensively for maternal and newborn health and are showing emerging evidence of success in the management of non-communicable diseases. 2122

A final important component of service delivery structure that influences the availability to care is horizontal integration. Horizontal integration is the consolidation of multiple types of service – including promotive, preventive, rehabilitative, and even palliative – in a single facility. 23 Indeed, to effectively provide horizontally integrated services, providers must be adequately trained in a range of primary care relevant services. In LMIC, often different services are offered on separate days of the week, requiring multiple visits for patients with more than one specific health need. Through horizontal integration, facilities can minimize follow-up visits and increase the efficiency and availability of providers.

-

Provider competence Provider competence entails having and demonstrating the knowledge, skills, abilities, and traits to successfully and effectively deliver high-quality services. entails having and demonstrating the “knowledge, skills, abilities, and traits” to successfully and effectively deliver high-quality services. 24 Competency Competency means to demonstrate a level of ability on a specific task or achieve a level of performance. can be built during pre-service and in-service education and is not limited to technical knowledge. Provider competence Provider competence entails having and demonstrating the knowledge, skills, abilities, and traits to successfully and effectively deliver high-quality services. is important for ensuring technical quality, ensuring experiential quality from the patient perspective, improving patient-provider respect and trust, and achieving effective coverage and good health outcomes in order to achieve UHC.

In order to improve health outcomes, it is important to focus on both provider availability and competence. While provider supply is a challenge in many LMICs, 3 providers’ ability to deliver high-quality care is also a limiting factor. A curious paradigm in health is the “know-to-practice” gap where providers may be appropriately trained and aware of standards of care but they do not follow this knowledge during a typical consultation with patients. 25 Thus, it is important to distinguish if a provider is not providing high-quality care due to a lack of knowledge and training or because they are limited in being able to administer care as they learned it.

Competent providers should also receive high-quality and regular supportive supervision. In contrast to typical supervision, supportive supervision is a collaborative approach where managers work with providers to identify gaps and strategies to address them. Supportive supervision is discussed in greater detail in management of services.

Quality is often considered from two dimensions: technical and experiential. Technical quality includes care that meets standards and guidelines and is almost always learned during formal education or training. Conversely, experiential quality of care is measured from the patient perspective and includes a patient’s experience and satisfaction interacting with the provider.

Education and training

Pre-service education and training

Pre-service education is the first opportunity for providers to receive training that will influence technical quality. Most of the literature on education relates to program accreditation and licensing of professionals, discussed within the policy & leadership module. However, the WHO Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health provides a few suggestions for strengthening health education and training. It recommends that institutions and policies should be designed to be nimble enough to respond to local human resource needs. The strategy also suggests collaboration with Ministries of Education to ensure that primary and secondary school institutions prioritise science education in order to prepare students who choose to go into health professional education and training. Additionally, education programs and institutions should ensure that they are promoting equal opportunities for all individuals. 3 While the WHO strategy specifically discusses ensuring opportunities for women, equality of access to education should be promoted across all social strata and demographics including but not limited to caste, religion, race, and ethnicity.

In 2010, the Lancet Commission on the Education of Health Professionals for the 21st Century was established to explore an ideal vision for medical education given rapidly improving technology as well as worldwide demographic and epidemiological transitions. The Commission unsurprisingly found that medical education institutions are maldistributed across the world, with 36 countries having no medical schools at all. Across countries, a fairly stagnant medical curriculum has resulted in mismatched provider competencies and patient needs. The vision of the Commission is that “all health professionals in all countries should be educated to mobilize knowledge and to engage in critical reasoning and ethical conduct so that they are competent to participate in patient and population-centred health systems as members of locally responsible and globally connected teams.” 26 Achieving this vision requires instructional and institutional reforms.

The Lancet Commission focused their reviews and recommendations on medicine, nursing-midwifery, and public health education though they recognized the importance of competencies for broader cadres such as community health workers. Through the development of a framework and a robust review of historical medical education, the Commission suggested 10 categories for reforms:

- Competency Competency means to demonstrate a level of ability on a specific task or achieve a level of performance. -based curricula – curricula should be designed based on competencies that are related to local needs

- Interprofessional education – providers should train and learn together to improve collaboration and reduce hierarchical relationships. Because team-based care organization is an aspiration for high-quality primary health care, this type of training can help prepare providers for in-service collaboration. Interprofessional education is discussed in greater detail in the team-based care organization module.

- Use of information technology (IT) – as IT becomes more pervasive, even within low and middle-income countries, educational institutions should take advantage of the learning opportunities it offers while also preparing providers to use IT in-service to improve the quality of care.

- Harness global resources but adapt locally – students should be able to take advantage of global learning resources while also learning how this knowledge relates to and can be adapted to local needs.

- Strengthen educational resources – countries should invest in the professional advancement of medical educators. As with in-service medical providers, educators should have stable career paths, frequent evaluation, and incentives for good performance.

- Use competencies as criteria for the classification of professionals – in order to reduce silos within medicine, all providers should receive education related to attitudes, values, and behaviours with additional specialized competencies.

- Joint planning mechanisms – educational planning should be a joint process, particularly between the Ministries of Health and Education. These planning mechanisms should ensure that opportunities are created for marginalized populations.

- Expand academic centres to academic systems – medical education should extend beyond the education institution and teaching hospitals to communities and primary health care facilities.

- Link networks, alliances, and consortia between educational institutions – using regional and global consortia and information technologies, countries should aim to share knowledge, tools, and resources, particularly to enhance medical education in countries where there is a shortage of medical educators.

- Encourage inquiry – institutions should work to encourage a culture of curiosity and inquiry.

It should also be noted most curricula lack a focus on comprehensive primary care service delivery, despite the substantial workforce need. Training opportunities are often limited to hospitals, and many medical schools lack a department of family medicine or general practice, resulting in a training environment ill-suited to learning about the practical application of skills in outpatient medicine and primary care. In support of high-quality primary health care specifically, institutions providing health professional education should prioritize primary care-related competencies in their curricula and integrate core principles of primary care throughout training. 27 Students benefit from early exposure in their education to comprehensive primary care settings and the accompanying competencies. Similarly, other health professionals expected to work as part of a primary health care team should have exposure to training in the core principles of primary care service delivery as a regular part of their undergraduate curriculum. 26

The value and rigour of primary care should be a core component of strong medical professional training, with leading students encouraged to contribute to further academic study in the field. In addition, students should be exposed to the importance of post-doctoral training in primary care, emphasizing the value of discipline-specific training to ensure sufficient workforce competency, as with other medical specialities.

Ongoing training

Particularly when scopes of practices are expanded, it is important to make sure that health workers are licensed to deliver these tasks to ensure patient safety. There is strong evidence that the quality of care provided by mid-level practitioners is comparable to doctors for vertically-oriented outcomes in maternal health as well as communicable and non-communicable diseases. 28 Less is known about their impact on overall outcomes in routine delivery of comprehensive primary care services. Nonetheless, the existing evidence provides strong support for the consideration of shifting responsibilities in targeted clinical areas to mid-level providers in many primary care settings. It is important, however, to ensure that these providers are supported by necessary inputs, training, and supervision to carry out the tasks that are delegated to them.

There is growing evidence that community-based programs may be a cost-effective strategy to improving coverage of certain health services. 29 These services are generally delivered by providers with limited training. Here, this cadre of providers is referred to as “community health workers” (CHWs) – they may be referred to differently across contexts. The benefit of community-based approaches depends on full integration into the health system. CHWs must be appropriately educated, remunerated, supervised, and integrated into multidisciplinary teams. Globally, there is often little regulation and standardization of CHW training within and between countries, partially due to wide differences in CHWs’ expected tasks and skills across settings. 30 As a result, the length of pre-service training for CHWs varies significantly, from a few days to more than 6 months. 31 A report from Practitioner Expertise to Optimize Community Health Systems suggests frequent and ongoing in-service training in addition to pre-service training and use of practice-based learning strategies. Determining the appropriate pre-service and in-service training depends on a number of considerations including 1) priorities of the national healthcare system; 2) priorities of local stakeholders; 3) local and national epidemiology and needs; 4) balancing of responsibilities between CHWs and other providers in the region; and 5) the make-up and competencies of the health workforce.

Additional resources on CHWs from the WHO can be found here.

Finally, as information technology becomes more advanced and widespread, peer-to-peer learning and collaboration communities have become quite common. A few of these communities include:

- The Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage – this network of global health policymakers collaborate using collective knowledge, practice, and research to create knowledge management products that will advance the agenda of Universal Health Coverage.

- The Global Health Delivery Project – This is an initiative designed by Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University in the United States that includes case studies, courses, and online communities.

- The Quality of Care Network – The network has convened a number of countries to share how they have made improvements in maternal, newborn, and child health. They have created a space for country stakeholders to share their experiences with improvement and learn from one another.

Continuing professional development

Medical education and training should also be ongoing throughout a provider’s career, and continuing professional development (CPD) is an important opportunity to keep providers’ technical skills refreshed and updated. CPD typically includes certification or re-certification, and there is a dearth of evidence on the best way to administer CPD in LMIC, particularly related to primary health care. In order to promote uptake of new skills and promote group learning, CPD may be best delivered in primary care facilities, though this is often not the reality. 32 Global partnerships and private sector corporations support or provide a significant amount of CPD in LMIC, although these are often specifically focused on vertical programs. For instance, PEPFAR conducted more than 3.7 million continuing education encounters between 2003 and 2008, and the Global Fund conducted 14 million between 2002 and 2012. 33 These partnerships can be quite complex and require effective communication and buy-in from local stakeholders as well as close consideration of the local context. Expert consultation with individuals involved in these global continuing medical education partnerships surfaced the following suggestions:

- Programs can address the knowledge-to-practice gaps if high and low-income countries come together to address education needs.

- Programs can work more efficiently if resource-rich countries and resource-poor countries share resources and goals for training.

- A needs assessment is an important first step for partnerships to develop educational content that is context-specific.

- Continuing medical education programs benefit from local leaders who are well versed in the local environment. 33

Most countries will have a regulatory board for each cadre, with the application, enforcement, and involvement of these regulatory boards differing significantly between and within countries. Incorporating continuing professional development requirements into these regulatory board frameworks may improve opportunities for continuing professional development and ensure some degree of accountability for professional development.

Protocols & tools

Protocol-based approaches

There are a number of protocol-based approaches and decision-making tools that are used to improve the technical quality of care in low and middle-income settings. Three such strategies – developed by the WHO - are Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI), Integrated Management of Adolescent and Adult Illness (IMAI), and the Package of Essential Non-Communicable Disease Interventions (PEN). Some of the decision-making tools and charts for the three strategies are available on the WHO website:

- Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI)

- Integrated Management of Adolescent Illness (IMAI)

- Package of Essential Non-Communicable Disease Interventions (PEN)

The three strategies include curative and preventive interventions that can be administered in communities and homes as well as in facilities; however, there is significantly more published literature on IMCI relative to the other two. IMCI presents stepwise approaches to case management of sick children including checking vital signs, identifying danger signs, and inquiring about symptoms and nutritional and immunization status. 34 However, findings from the implementation of these strategies are mixed. A 2015 systematic review explored the effectiveness of four programs that implemented IMCI, finding low-certainty evidence that IMCI may lead to fewer deaths among children under five but has little or no effect on the number of children suffering from stunting and probably no effect on the number of children suffering from wasting or receiving measles vaccines. 35 An evaluation of IMCI implementation in Ghana found that adherence to guidelines was poor and did not influence outcomes. 34 Further, it seemed that providers may have been too overburdened and unmotivated to adequately implement IMCI guidelines. This suggests that these protocols may need to be adapted to facility needs, better integrated into the coordinated workflow of comprehensive primary care service delivery, and coupled with interventions to improve the quality of the work environment and provider motivation in order to be effective.

A similar tool is PACK (Practical Approach to Care Kit) Adult, a primary care guide developed by the Knowledge Translation Unit at the University of Cape Town. 36 The guide begins with 40 common symptoms and uses checklists and algorithms to help providers manage 20 chronic conditions. The guide is supplemented by a robust training program where trainers visit the implementing clinics regularly to ensure the integration of PACK with existing facility practices. More information on the tool and its adaptation to multiple settings can be found on the PACK Adult website.

The WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist is another tool that can be used in primary care settings to improve maternal and perinatal care practices. The checklist outlines practices for birth attendants at four points: 1) upon admission; 2) just before pushing (or before Caesarean); 3) soon after birth; and 4) before discharge. The checklist is meant to guide practices and give providers opportunities to pause and ask important questions regarding the progression of labour, maternal, and neonatal health. The WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist is accompanied by an Implementation Guide. 37

-

Work motivation has been defined as an “individual’s degree of willingness to exert and maintain an effort toward organizational goals” and is the result of a provider’s interactions with team members and other co-workers, organizational goals and culture, and larger socio-cultural expectations and values. Motivation captures intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics that affect the behaviour and performance of providers in a health system. Intrinsic motivation Intrinsic motivation is a feeling of accomplishment driven by organisational goals and the impact of one’s work on patients and communities. is the feeling of accomplishment driven by organizational goals and the impact of one’s work on patients and communities. Alternatively, extrinsic motivation is driven by monetary or non-monetary individual or environmental incentives. 38 Within motivation, the literature has a particular focus on the degree of provider autonomy, degree of remunerative motivation, supportive supervision, options for professional development, and level of burnout.

Provider motivation Provider motivation “...in the work context can be defined as an individual’s degree of willingness to exert and maintain an effort towards organisational goals.” Motivation captures intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics that affect the behaviour and performance of providers in a health system. is closely related to both burnout and satisfaction. Providers who are more satisfied with their jobs are often more motivated, and burnout typically occurs when providers are overworked and unsatisfied. However, even providers who are experiencing burnout may still be motivated if they are intrinsically committed and passionate about the work they do and the impact they drive. Therefore, motivation is typically considered from two dimensions: extrinsic motivation and intrinsic motivation.

Extrinsic motivation Extrinsic motivation refers to motivation that is incentivized by anything other than personal drive and commitment. Extrinsic motivation may be related to monetary or non-monetary individual incentives or environmental incentives. Individual monetary incentives may include salary, pensions, insurance, travel, child care, heat, retention allowances, subsidised meals, subsidised clothing, and subsidised accommodation.

Extrinsic motivation Extrinsic motivation refers to motivation that is incentivized by anything other than personal drive and commitment. Extrinsic motivation may be related to monetary or non-monetary individual incentives or environmental incentives. Individual monetary incentives may include salary, pensions, insurance, travel, child care, heat, retention allowances, subsidised meals, subsidised clothing, and subsidised accommodation. refers to motivation that is incentivized by anything other than personal drive and commitment. Extrinsic motivation Extrinsic motivation refers to motivation that is incentivized by anything other than personal drive and commitment. Extrinsic motivation may be related to monetary or non-monetary individual incentives or environmental incentives. Individual monetary incentives may include salary, pensions, insurance, travel, child care, heat, retention allowances, subsidised meals, subsidised clothing, and subsidised accommodation. may be related to monetary or non-monetary individual incentives or environmental incentives. Individual monetary incentives may include salary, pensions, insurance, travel, child care, rural location, heat, retention allowances, subsidized meals, subsidized clothing, and subsidized accommodation. 17

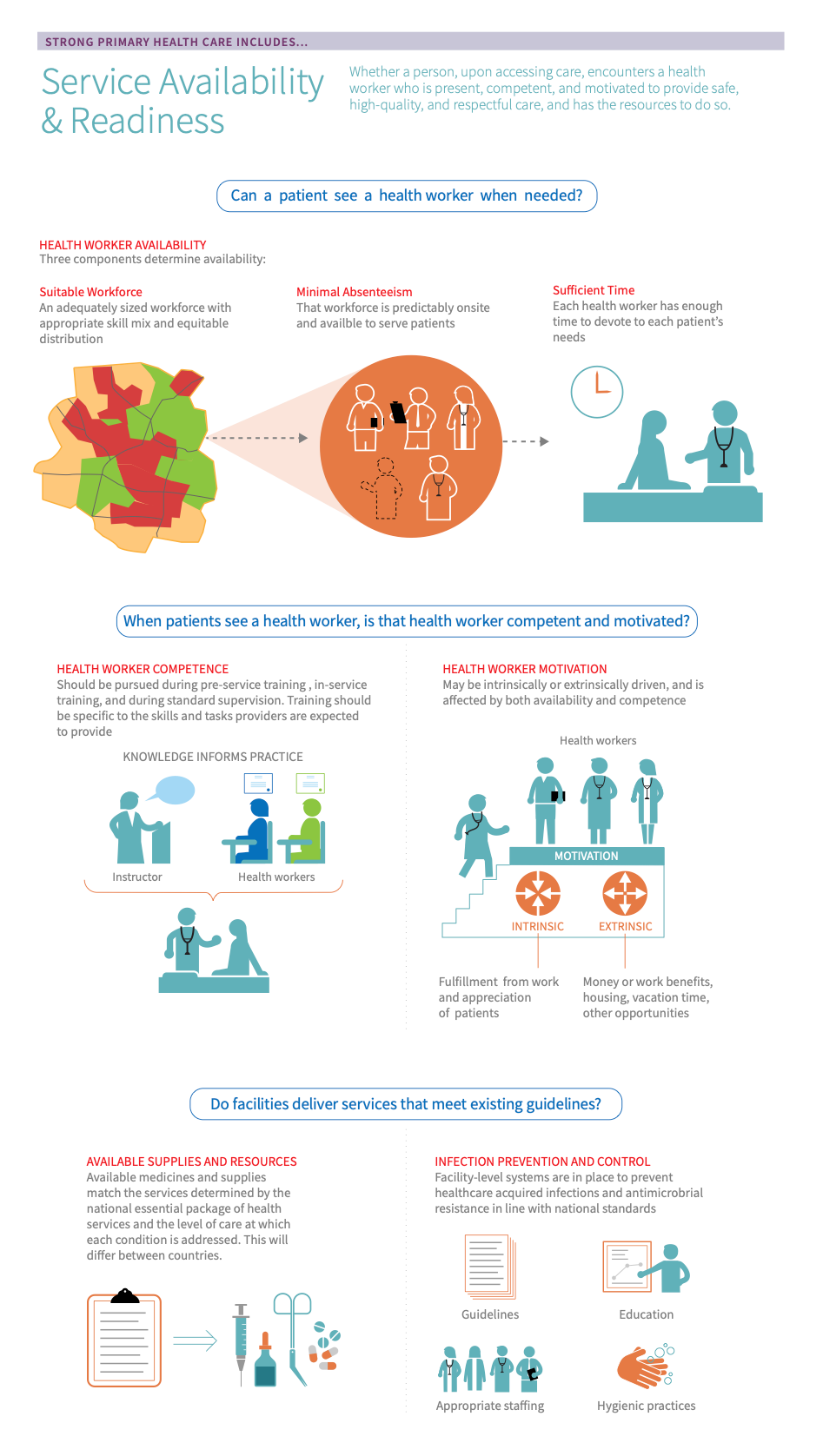

It is important to note that all provider payment methods result in different incentives for providers. These incentives are described in Table 1. The Joint Learning Network has developed a useful resource on financing and payment models based on country implementation experience as well as a manual and online course on the costing of health services for provider payment. Payment systems will be discussed in greater detail beyond their relevance to provider motivation within the purchasing & payment systems module.

Source: adapted from Hongoro 2006 and JLN Costing of Health Services for Provider Payment 1739

Performance-based financing Providing financial incentives to providers based on the achievement of pre-defined, measurable, and agreed-upon performance targets. (PBF - also called results-based financing or pay-for-performance) is a mechanism that is commonly used to motivate improved quality of care and increase the volume of services. PBF approaches are typically used in conjunction with other provider payment mechanisms and can be adapted to incentivize particular actions. 39 However, successful implementation of PBF is contingent upon strong managerial capacity and effective information systems to track performance. 40

PBF approaches have been implemented in various LMICs over the past decade. There is mixed and limited evidence of their effectiveness. In some instances, PBF has been found to be expensive, inequitable, promotive of perverse incentives, and as a result of poor design and adaptation, it may be deleterious to service delivery. 41 Implementation of PBF may detract from other infrastructure or human resource investments if not carefully designed. Additionally, in LMIC, PBF has been nearly always funded by donors, raising concerns about appropriate contextual adaptation, ownership, and sustainability.

Non-financial individual incentives that influence provider motivation include vacation days, flexible working hours, access to training and education, sabbatical and study leave, planned career breaks, occupation health, functional and professional autonomy, technical support and feedback systems, transparent reward systems, and being valued by the organization. 17 These incentives can be planned and implemented at the facility level and require the oversight and leadership of facility managers.

Finally, environmental incentives relevant to provider motivation include amenities, transportation, a job for spouses, and school for children. Improving these environmental conditions require intersectoral collaboration and action. These environmental conditions also influence provider availability, particularly in rural areas. 17

Intrinsic motivation Intrinsic motivation is a feeling of accomplishment driven by organisational goals and the impact of one’s work on patients and communities.

Intrinsic motivation Intrinsic motivation is a feeling of accomplishment driven by organisational goals and the impact of one’s work on patients and communities. is the feeling of accomplishment or satisfaction with organizational goals and with the impact of one’s work. 38 Most motivation-related incentives and interventions are monetary, and relying on these methods alone may not be sufficient to improve all aspects of motivation. 42 However, these interventions can be paired with efforts to improve provider satisfaction through intrinsic (or internal) motivation. Interventions related to intrinsic motivation are typically pursued at the facility or community level.

Patient-provider interactions as experienced from the perspective of patients are addressed in primary care functions. However, patient-provider interactions from the providers’ perspective are an important determinant of providers’ intrinsic motivation. For that reason, community engagement and support may help foster relationships between providers and communities and contribute to improved intrinsic provider motivation. A study in Ghana evaluated the effect of Systematic Community Engagement (SCE) on intrinsic motivation among health workers. 10 SCE was pursued through community group assessments of healthcare quality based on participants’ most recent experiences in a given facility. 43 These assessments were used to guide facility management and subsequent interventions. The findings from this study suggested that intrinsic motivation was stronger among providers in intervention facilities compared with facilities that did not implement SCE. The implementers hypothesized that providers working in facilities that were assessed by community members would have more positive interactions with patients than those working in facilities that were not assessed by community members. While promoting intrinsic motivation through community engagement should not replace monetary incentives, it may be effective in complementary ways.

While the purpose of community engagement in the Ghanaian example above was to receive feedback on facility-level quality, more direct interactions between community members and providers may also be a strategy for improving provider motivation. Particularly when providers are posted in unfamiliar or remote areas, community support is important to make health workers feel welcomed and to connect them with the community, which may in turn help promote intrinsic motivation. 12 Although it has not been studied in the context of provider motivation, the Community Health Planning and Services (CHPS) program in Ghana has integrated community engagement into many aspects of implementation. In particular, community-based providers are introduced to and approved by the community during community meetings, called durbars. 44 By socializing providers and the services they deliver to communities, providers may feel more supported in the work they provide and motivated by the impact they make.

-

Facility readiness is the availability of the physical and human resources necessary to deliver services. These include the presence of amenities, equipment, precautions for infection prevention, diagnostic capacity, and essential medicines. 45 However, not all facilities need access to the same resources; the way in which the health system in a given country is organized, what their essential package of health services includes, and where care is delivered will determine what constitutes readiness at a particular facility.

Organisation of services

As discussed in organisation of services, each country will structure their primary health care services and levels of care differently, which will influence facility readiness. The different steps required to establish a well-organized health system are discussed in detail in organisation of services and include:

- Establishing an essential package of health services that is specific to the burden of disease in the country as well as the leading causes of morbidity and mortality

- Clearly defining the levels of care within the health system and which services are provided at each level and in various settings. For example, which services are provided in a community-based setting versus in facilities

- Establishing pathways of care through the health system for patients with relevant health conditions

Therefore, readiness will look different across countries and within countries across different sites. The medicines and supplies necessary to deliver services will be dictated by the essential package of health services and the level of care at which each condition is traditionally addressed. The relevant competencies of providers will also be shaped by these considerations. Therefore, consulting these existing guidelines is a crucial first step to understanding what readiness means in a given facility. The organisation of services module provides information on how to develop an essential package of health services, define levels of care, and establish care pathways as well as the importance of integrating a diverse and representative team in this process.

Infection prevention and control

Regardless of the type of services provided in a given facility, infection prevention and control (IPC) measures are necessary at all care sites to ensure the safety of patients and providers by preventing health care-associated infections and combat antimicrobial resistance. The WHO has produced a robust guideline on core components of IPC programmes with manuals for both the national and facility levels. National-level guidelines primarily relate to the policymakers and the establishment of national IPC programs and action plans, while facility-level guidelines are intended for facility-level administrators who implement local IPC programs. 46 The guide proposes the following eight core components of IPC programs: