|

|

|

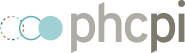

Well-structured and dynamic processes for adjusting to population health needs strengthen the resilience and responsiveness of a health system.

They also underpin a country’s ability to develop a transparent, participatory, and evidence-informed national health strategy that meets the complex needs of its population.

Adjustment to population health needs includes regular collection and analysis of data and evidence about population health status and needs, appropriate use of this information to set and implement priorities, and continuous assessment and monitoring of changing population health needs and contexts. Adjustment to population health needs also involves the process of stimulating the development and making use of new and existing evidence, research, and data to continually learn and adapt to changing population health needs. It should take into account health determinants, trends and risks as well as a country’s epidemiological, political, socioeconomic, and organizational context with a focus on equity.

A few key processes/mechanisms for adjusting to population health needs include:

- Priority setting The process of making decisions about how best to allocate limited resources to improve population health. : the process of making decisions about how best to allocate limited resources to improve population health.

- M&E: processes by which stakeholders collect, measure, and use data to assess and maximize the impact of projects, programs, or social initiatives over time.

- Innovation & learning: a characteristic of a health system that enables flexibility and iteration in order to continuously improve services and ultimately drive improved health outcomes.

- Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. : a core public health function which involves the “continuous, systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data”. 31

-

The National Health Strategy (NHS) sets the medium- to long-term vision for the health sector, including what activities and investments are needed to achieve health sector objectives in the most efficient way possible. It is the “blueprint” for policies, plans, and strategies in the health sector. 1 When done effectively, priority setting, M&E, surveillance, and innovation and learning processes help to ensure that the NHS is evidence-based and well-implemented across the health system. Below, we describe how each of these processes fits into the development, implementation, and evaluation of the NHS:

Priority setting The process of making decisions about how best to allocate limited resources to improve population health.

Priority setting The process of making decisions about how best to allocate limited resources to improve population health. directly feeds into the content of the NHS. It generally follows the situation analysis and precedes costing and budgeting exercises. A participatory, transparent, and evidence-based priority setting exercise is fundamental to designing and updating the NHS in line with population health needs. 2

Monitoring & evaluation

M&E is a critical component of the NHS. When done effectively, it helps to ensure that the NHS meets strategic goals and objectives. M&E mechanisms are typically specified during the strategic planning phase, whereby M&E activities across all major disease programs are linked to NHS milestones and targets. The M&E plan is typically prepared as a separate strategy document. The evidence from M&E processes can be used to inform future priority-setting and planning exercises. For example, the final evaluation of a national health strategy could serve as the initial situation analysis and evidence-base for subsequent priority-setting and planning exercises. (3,4)

Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health.

Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. is a primary source of data for M&E and priority-setting efforts. It provides up-to-date information on population health needs. As such, surveillance data helps to ensure that the content of the NHS reflects current population health needs. 4

Innovation & learning

While not an essential component of / input for the NHS, mechanisms for innovation and learning can help key stakeholders to make better, more sustainable decisions in the long term. For example, countries that invest in increasing the learning capabilities of their health system (i.e. establishing local institutions for innovation &/or research) can accelerate the generation, adaptation, &/use of knowledge that is reflective of local priorities. This can help decision-makers to devise more impactful, relevant strategies. 567

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Every country should improve their ability to adjust to population health needs. Before taking action, countries should first determine where to target improvement efforts. Read on to learn how to use country data to:

- Make informed decisions about where to spend time and resources

- Track progress and communicate these updates to constituents or funders

- Gain new insights into long-standing trends or surprising gaps

Countries can measure their performance using the Vital Signs Profile (VSP). The VSP is a first-of-its-kind tool that helps stakeholders quickly diagnose the main strengths and weaknesses of primary health care in their country in a rigorous, standardized way. The second-generation Vital Signs Profile measures the essential elements of PHC across three main pillars: Capacity, Performance, and Impact. Adjustment to population health needs is measured in the Governance domain of the VSP (Capacity Pillar).

If a country does not have a VSP, it can begin to focus improvement efforts using the subsections below, which address:

- Key indications

-

If your country does not have a VSP, the indications below may help you to start to identify whether adjustment to population health needs is a relevant area for improvement:

- Poor data collection, analysis, use, & dissemination practices: If data are not consistently collected, analyzed, and used to set health priorities at the national and sub-national level for the burden of disease, user needs and preferences, service delivery evaluations, and cost-effectiveness, it may indicate that priority setting approaches and/or mechanisms for data collection, analysis, use, and dissemination needs reform. It may also indicate that existing M&E processes are fragmented or underutilized.

- Narrow &/or inconsistent stakeholder engagement: If diverse stakeholders are not systematically engaged and consulted during decision-making processes (i.e. no community representatives are presented during the priority setting exercise), it may indicate that strategic planning and decision-making processes require reform.

- Inefficient or ineffective allocation of resources: If the allocation of resources is not based on data and evidence (including evaluations/assessments of current and past national health strategies, the situation analysis, and the results of the priority setting exercise) it will likely compromise the cost-effectiveness and efficiency of reforms.

- Insufficient or non-existent mechanisms for innovation and learning: If mechanisms for innovation and learning are not in place (ie, the existence of national knowledge management or evidence review process), it can prevent new or emerging data, evidence, and/or technologies from being introduced. A weak culture around learning, innovation, and quality improvement can also stifle innovation and knowledge-sharing between stakeholders.

- Weak or delayed surveillance, response, and management measures: If critical surveillance, response, and management measures are poorly functioning or not in place (i.e. risks are not communicated to stakeholders in a timely manner and/or the local network of providers is ill-equipped to meet the needs of the population) it may indicate that priorities in your our health system are not reflective of population health needs and/or poor allocation of resources. It may also point to a breakdown in information sharing and use across levels of care.

- Key outcomes and impact

-

Countries that strengthen their ability to adjust to population health needs may achieve the following benefits or outcomes:

- Efficient and effective allocation of resources for PHC: Evidence-informed priority setting and M&E exercises help decision-makers to get an accurate picture of population health needs. When they use these data to set priorities and improve on previous strategic planning exercises, it enables them to make the best use of resources over time. 18

- Responsiveness: Health systems and the environments in which they operate are constantly in flux, due to contextual changes such as population composition and political economies. At the same time, the fields of medicine and public health are dynamic, with new information, guidelines, and best practices emerging frequently. The aforementioned mechanisms can strengthen a country’s ability to adapt to and learn from these external forces to ensure that the health system is evolving to effectively and equitably meet population health needs with high-quality care. 89101112

- Resilience: In addition, routine and non-routine surveillance, M&E, and research activities strengthen a country’s ability to identify and respond to public health problems. For example, countries can use the data generated from surveillance activities to better prevent, prepare for, and respond to health emergencies. 8131415

- Quality: Well-coordinated M&E and research activities enable countries to monitor the effectiveness of policies and programmes over time. In turn, they can use this data to improve the design and implementation of future programmes in line with country targets for PHC. For example, they can use the data generated from M&E and health research activities to get a better understanding of what is and is not working in the health system, as well as potential solutions to these problems. 8131415

- Equity in health: Priority setting, M&E, and innovation and learning mechanisms that are built on transparent, participatory processes help to ensure that all stakeholders’ voices are heard, thus promoting equity in health. In addition, M&E activities help to hold decision-makers accountable to these interests, as well as PHC-related targets that promote their health and well-being, such as equity in the delivery of health services. 141617

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Explore this page for a curated list of actions to improve policy & leadership, which embark on:

- An explanation of why the action is important for a country’s ability to adjust to population health needs

- Descriptions of activities or interventions countries can implement to improve a country’s ability to adjust to population health needs

- Descriptions of the key drivers in the health system that should be improved to maximise the success or impact of actions

- Relevant tools & resources

Key actions:

-

Reliable and timely health data and information are a cornerstone for success in a health system. Data provides the performance insights that countries need to determine whether they are meeting their goals and targets and if not, why. Thus, countries should strengthen their institutional capacity to collect, analyze, use, and share data (i.e. surveillance data, programme monitoring data, patient outcomes and experience data). Doing so will increase their ability to deliver interventions that meet the needs of their population over time. It will also strengthen their capacity to prevent, prepare for, and respond to health emergencies, as demonstrated by the COVID-19 pandemic. 8131415

Key activities

All levels

The below activities apply to all information systems for health (HIS), including those that are important for M&E (for more information about the key types and functions of HIS, see the information and technology module):

- Strengthen data governance policies: Strengthening and/or implementing policies and guidelines for data collection, analysis, use, and dissemination can increase the quality and reliability of data as well as its use for decision-making processes. Such policies may also include a national strategy for eHealth. It is important to recognize the political complexities around data release and use when devising policies. 1718

- See the WHO’s Global Strategy on Digital Health and their National eHealth Strategy Toolkit for additional guidance.

- Institutionalize, coordinate, and harmonize HIS and M&E systems, such as by 1920

- Building internal demand for the active collection, analysis, and use of evidence for informed policymaking, programme design, and M&E. For example, countries should present research evidence and findings in an easy-to-understand format and make this information accessible across sectors and levels of the health system.

- Clarifying stakeholder roles and responsibilities in country action plans (including the M&E plan) and using evidence from evaluations to assess whether roles are being carried out as planned.

- To aid in this step:

- Establish a central ministry or agency responsible for stewarding and coordinating health information systems and M&E efforts in the country (these may be separate entities/units, depending on the context). 820 For example, Fiji established a Health Information, Research and Analysis Unit within their MoH and Malawi introduced a joint action plan for strengthening HIS and M&E.

- Clearly define staff roles and responsibilities across the different platforms, including who is responsible for collecting, monitoring, and reporting health data and information and who is responsible for conducting evaluations. Ensure that roles and responsibilities are consistent across different projects, agencies, and/or governmental levels. 2021

- Appoint a focal point person(s) who coordinates HIS and M&E activities with the programme unit(s) and other stakeholders. To promote harmonization, focal points should coordinate HIS and M&E activities with any central ministries or agencies for HIS and M&E. 22

- See pages 9 - 10 of the UW’s Development Policy and Finance team’s report on government M&E systems and chapter 5 of the WHO’s data quality assurance module for additional guidance.

- To aid in this step:

- Harmonizing government HIS and M&E activities, for example by establishing a mandate for the office in charge of coordination; building staff capacity to conduct M&E activities; and increasing funding for coordination activities within and between M&E and HIS systems.

- Harmonizing government and development partner HIS and M&E systems 19

- To aid in this step, use the following set of principles: 23

- Make HIS and M&E systems country-owned and led. For example, development partners/ donors should engage country leadership in the design and implementation of their HIS and M&E systems.

- Work with partner countries to rely on country-owned M&E systems. For example, use a participatory approach to strengthen country capacities and demand for results-based M&E.

- Design M&E systems to meet the priorities and accountability needs of partner countries (rather than just donor’s information and accountability needs)

Ensure that all M&E systems are simplified, harmonized, and appropriately timed in relation to national policy and budget processes.

- See pages 24 - 27 of the UW’s Development Policy and Finance team’s report on government M&E systems and chapter 5 of the WHO’s data quality assurance module for additional guidance.

- To aid in this step, use the following set of principles: 23

- Strengthen data collection and monitoring systems, through 1920

- Selecting and aligning indicators across HIS and M&E systems, and ensuring that on-the-ground data collection aligns with this official list of indicators. See step 2 of the sub-action below for a recommended set of indicators for PHC.

- See page 13 of the UW’s Development Policy and Finance team’s report on government M&E systems for additional guidance.

- Increasing the data collection and aggregation capacity. For example, countries should establish documented rules for data collection, including what data to collect, who collects it, and how often. Countries should also establish rules for data aggregation and ensure that staff at all levels of the health system are trained and equipped to deliver on these rules.

- See pages 13 - 14 of the UW’s Development Policy and Finance team’s report on government M&E systems for additional guidance.

- Introducing more sophisticated data capacities (if feasible), including processes for verifying data quality and integrating data collection, aggregation, and verification using information technology tools and supportive supervision

- See pages 14 - 15 of the UW’s Development Policy and Finance team’s report on government M&E systems for additional guidance.

- Selecting and aligning indicators across HIS and M&E systems, and ensuring that on-the-ground data collection aligns with this official list of indicators. See step 2 of the sub-action below for a recommended set of indicators for PHC.

- Improve the analysis and use of data generated by HIS and M&E systems, including by: 1920

- Developing a strategic M&E framework that details planned activities and outputs. The framework should allow governments to evaluate how well they have done in implementing their strategy, as well as expected outcomes.

- See page 15 of the UW’s Development Policy and Finance team’s report on government M&E systems for additional guidance.

- Conducting an implementation assessment, which is a type of performance evaluation. It uses output and outcomes indicators to examine how well the M&E strategy is being implemented in different contexts.

Budget

A document that outlines forecasted revenue and planned expenditure for an entity (government, subnational unit, or health facility) over a defined period of time. Budgets indicate how funds are meant to be allocated to achieve certain objectives.

or audit evaluations are a common type of implementation assessment.

- See page 16 of the UW’s Development Policy and Finance team’s report on government M&E systems for additional guidance.

- Conducting an impact evaluation, which is another type of performance evaluation. It uses outcomes data to evaluate the impact of M&E activities over time. Well-executed impact evaluations tend to use a combination of time series and control groups to determine whether activities are achieving desired outcomes.

- See pages 17 - 20 of the UW’s Development Policy and Finance team’s report on government M&E systems for additional guidance.

- Conducting a routine, annual, or periodic assessment of data facility- and/or district reported data 8

- See the WHO’s data quality assurance toolkit for additional guidance

- Consistently using HIS and M&E data to influence planning and budgetary decisions.

- To aid in this step, countries should:

- Outline plans for institutionalizing the use of results information during the creation of their M&E plan. In addition, countries should disseminate M&E results to a diverse array of stakeholders, including the public, civil society organizations, and development partners.

- Continuously collect data on diseases and events of public health significance (including the burden of diseases data) from both indicator-based sources and community-based or crowd-sourced data. 24252627

- See pages 20 - 21 of the UW’s Development Policy and Finance team’s report on government M&E systems for additional guidance.

- To aid in this step, countries should:

- Developing a strategic M&E framework that details planned activities and outputs. The framework should allow governments to evaluate how well they have done in implementing their strategy, as well as expected outcomes.

- Ensuring timely, systematic reporting of health data across levels of care. Closed feedback loops should be in place between facilities, sub-national regions and the centralized levels of the health system to ensure that the data actually informs action. The flow of information from the national level back to the facility is particularly important for response to incidents, as well as for the overall integration of information systems into population health management and decision-making processes.

- To assess the reliability and quality of these feedback loops stakeholders should consider factors such as:

- Does information flow from the national level back to the facility level and back?

- Are interoperable, interconnected, and electronic communication channels and information systems in place and consistently functioning?

- Do staff have identified communication channels to report to? Are there trained staff with the necessary expertise and processes to investigate and respond to reports?

- If there are gaps, stakeholders should identify and seek to understand why there are gaps, such as whether they are due to inputs (i.e. information systems and workforce), policies, or other factors.

- To assess the reliability and quality of these feedback loops stakeholders should consider factors such as:

Related elements

Relevant tools & resources

- Data.org, 2022: Epiverse - distributed pandemic tools program

- PAHO, 2022: ENLACE - Data Portal on Noncommunicable Diseases, Mental Health, and External Causes

- WHO, 2022: Child health and well-being dashboard

- WHO, 2022: Hub for pandemic and epidemic intelligence

- WHO, 2022: SCORE data collection tool

- WHO, 2022: Toolkit for routine health information systems data

- GHS Index, 2021: Global Health Security Index

- UN, 2021: SDG Global Database

- World Bank Group, 2021: Service delivery indicators health survey refresh fact sheet

- 3-D Commission, 2020: Data, social determinants, and better decision-making for health

- Dover and Belon, 2019: The health equity measurement framework: a comprehensive model to measure social inequities in health

- Partners in Health, 2018: UHC Monitoring and Planning Tool

- WHO, 2017: Strategic Framework for Effective Communications

- WHO, 2010: Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems - Information Systems

- WHO, 2012: National eHealth Strategy toolkit

- Strengthen data governance policies: Strengthening and/or implementing policies and guidelines for data collection, analysis, use, and dissemination can increase the quality and reliability of data as well as its use for decision-making processes. Such policies may also include a national strategy for eHealth. It is important to recognize the political complexities around data release and use when devising policies. 1718

-

The effective analysis, use, and dissemination of data and information support a country’s ability to adjust to population health needs in multiple ways: 828293031

Priority setting The process of making decisions about how best to allocate limited resources to improve population health. and planning: Stakeholders can use data to monitor and clarify the epidemiology of public health problems; and guide priority setting, planning, and policy decisions.

Programme design and implementation: Stakeholders can use data to monitor and improve the effectiveness of programmes over time. For example, they can use data from past evaluations to inform future policy decisions and programme design.

Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. , response, and management: Stakeholders can use data to strengthen public health response efforts in normal times and in a crisis, including via risk communication, testing and contact tracing, and case management and transmission control.

M&E and quality improvement: Stakeholders can use data to track and measure the impact of a public health intervention, including progress towards specified goals. It can also feed into progress and performance improvement efforts at different levels of the health system, ultimately strengthening the quality of care.

Innovation and learning: Stakeholders can use data to facilitate continuous learning, improvement, and innovation at different levels of the health system. For example, the data generated from biomedical, clinical, and health system research activities can be used to identify and address problems in the health sector.

Key activities & questions

- How reliably and consistently are data and information used to inform priority setting? To understand the degree to which data are used to set service delivery priorities, you might consider looking at the types of data, variation in data availability, and the use of these data:

- Are data and information systematically used to set priorities at the national and sub-national levels?

- Routine, non-routine, and research data are needed to get a fuller picture of a public health issue. Such data may include survey data, claims and cost data, and patient-generated health data, among others. 8

- Are data available, presented, discussed and applied through consistent processes for nearly all priority setting exercises?

- If not, are gaps due to problems with information systems, decision-making processes, policies, or other factors?

- Are data and information systematically used to set priorities at the national and sub-national levels?

- How reliably and consistently are the results of priority setting (including data from the situation analysis and past evaluations of the NHS) used to inform resource allocation? The results of the priority setting exercise (the most appropriate programs and interventions) should determine the allocation of resources all or nearly all of the time to improve population health. If resources are not being appropriately allocated, or current programs and interventions are not improving population health needs, you might look to the effectiveness of past priority-setting exercises and consider factors such as:

- Are existing and emerging health needs being assessed?

- Are stakeholders being engaged and held accountable for decisions?

- Is an explicit process for setting priorities being used?

- Are the values and context being appropriately considered?

- Are priorities in line with these needs, values and the local context? Do they also target/align with areas of poor performance?

- Are any decisions made being communicated to the relevant stakeholders, with systems in place for managing feedback and demands as a result of these decisions?

- If not, are gaps due to problems with governance, political and financial commitment, regulatory and legal structures, or other factors?

Related elements

- Policy & leadership

- Multi-sectoral approach

- Funding & allocation of resources

- Information & technology

- Population health management

Relevant tools & resources

-

Emergency

“An extraordinary situation in which people are unable to meet their basic survival needs, or there are serious and immediate threats to human life and well-being. Emergency interventions are required to save and preserve human lives and/or the environment. An emergency situation may arise as a result of a disaster, a cumulative process of neglect or environmental degradation, or when a disaster threatens and emergency measures have to be taken to prevent or at least limit the effects of the eventual impact. (UNDP)”

preparedness & response

- ReBUILD Consortium, 2022: Health systems resilience in fragile and shock-prone settings through the prism of gender, equity and justice: implications for research, policy and practice

- WHO, 2022: Hub for pandemic and epidemic intelligence

- WHO, 2022: Health systems resilience toolkit

- World Bank, 2021: Frontline: Preparing healthcare systems for shocks from disasters to pandemics

- USAID, 2021: Recommendations for strengthening health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond

- Prevent Epidemics: Multiple resources

- Exemplars in Global Health: Multiple resources

- Approaches to priority setting

- JLN, 2022: A Health Practitioner’s Handbook and Toolbox for Identifying the Poor and Vulnerable

- Rubinelli et al., 2022: WHO competency framework for health authorities and institutions to manage infodemics: its development and features

- DCP3, 2018: Disease Control Priorities Review (third edition)

- WHO, 2016: Priority setting The process of making decisions about how best to allocate limited resources to improve population health. for national health policies, strategies, and plans

- WHO, 2016: Strategizing national health in the 21st century: a handbook

- Center for Global Development, 2012: Report on Priority Setting in Health: Building Institutions for smarter public spending

- Data-driven decision-making

- AFIDEP, 2022: Evidence-informed policymaking training curriculum

- National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools, Learning Centre Module, 2022: Implementing Knowledge Translation Strategies in Public Health

- 3-D Commission, 2020: Data, social determinants, and better decision-making for health

- NNIP, 2013: Strengthening local capacity for data-driven decision making

-

M&E supports country efforts to adjust to population health needs in several ways: 1732

Enables countries to diagnose gaps and consequently make evidence-informed decisions about their national health sector strategic plan, including new programs, projects, and/or initiatives that should be implemented to achieve plan objectives

Helps countries identify ways to allocate and manage resources effectively and efficiently

Supports countries to assess the impact of their national health sector strategic plan, gaps in implementation, and programs, projects, &/or initiatives that were implemented successfully temporally and regionally

Provides countries with data they can use to convince decision-makers and/or donors to invest more in different programs, projects, and/or initiatives. They may also use this data to come up with alternative ways of addressing problems and/or achieving strategic goals.

Key activities

The WHO recommends six steps that countries can take to implement and sustain M&E for PHC at the national and/or sub-national levels (specifics on what should be included in an M&E plan are discussed in the M&E deep dive section of this module): 1733

- Step 1: Align PHC monitoring within existing national health sector plans, strategies, review processes, and related accountability mechanisms. For example, can promote accountability to strategic targets by building a results-based accountability framework into the M&E plan.

- Step 2: Tailor selection of indicators based on country policies, priorities, maturity of health system and gaps. See Annex 1 of the WHO’s M&E framework for a menu of indicators for country selection for PHC monitoring, by PHC component.

- Step 3: Set and monitor baseline values and country targets for PHC. Countries may consider conducting a situation analysis to inform baseline values.

- Step 4: Identify data sources and address major gaps through innovative methods and tools, such as via the use of EHRs and facility, patient-, and community-based surveys.

- Step 5: Strengthen capacities at national and subnational levels in data analysis, communication, and dissemination of results, including by:

- Implementing mechanisms to promote data access and dissemination such as annual statistical reports, national health observatories or portals, and an open data policy in the government, among others.

- Translating and using M&E data to inform policymaking and legislative proposals. Including via policy-relevant data analyses, evidence synthesis, and structured expert review processes.

- Using regular independent reviews to ensure data accountability and transparency and to drive remedial action as needed.

- Step 6: Conduct regular process of policy dialogues to guide actions, interventions, and investments for PHC performance improvement and management. This will help to ensure that data and evidence can be effectively applied within the existing regulatory environment (i.e. data release and use policies) and that decision-makers are actively bought into the use of M&E for performance improvement efforts.

Related elements

- Policy & leadership

- Multi-sectoral approach

- Funding and allocation of resources

- Information and technology

- Population health management (community engagement)

- Management of services (systems for improving quality of care)

Relevant tools & case studies

- Cross-cutting learnings:

- DEVEX: Software and resources for M&E professionals

- Global Fund: Compendium of resources on developing an M&E framework and strengthening in-country M&E systems

- Humans of Data: What is M&E? A guide to the basics

- Humans of Data: The 7 types of evaluation you need to know

- MEASURE Evaluation: Self-guided minicourse on M&E fundamentals

- MEASURE Evaluation: Compendium of tools and resources for M&E

- WHO: Measurement & monitoring framework for PHC

- WHO, 2019: Primary health care Primary health care (PHC) is “a whole-of-society approach to health that aims to maximise the level and distribution of health and well-being through three components: (a) primary care and essential public health functions as the core of integrated health services; (b) multisectoral policy and action; and (c) empowered people and communities.” on the road to universal health coverage: 2019 monitoring report

- World Bank: Good practice case studies for Resilience “The ability of a system, community, or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate to, and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner, including through the preservation and restoration of its essential basic structures and functions through risk management.” M&E

- World Bank: Volume on how to build M&E systems to support better government

- World Bank: Volume on how to build and embed strong M&E systems into decision-making processes in all sectors, including for policy design and policymaking

- World Bank: Handbook and case studies on how to build a results-based monitoring system

- World Bank: 10 key issues for diagnosis of a government’s M&E system

- USAID: Toolkit for high-quality M&E

- Using the M&E system

- WHO: Handbook for strategizing national health in the 21st century

- World Bank: Case study on using M&E to support performance-based planning and budgeting in Indonesia

- World Bank: Report on using care cascade analytics to identify challenges and solutions in service delivery and client outcomes

- The Global Fund: Strategic framework for data use for action and improvement at the country level

- Improving the quality of the M&E system

- WHO: Compendium of data collection and analysis tools for M&E and other performance improvement efforts, including the SCORE data collection tool

- World Bank: Handbook on the ten steps to a results-based monitoring and evaluation system

- MEASURE Evaluation: Portfolio for ensuring data quality for M&E

- Humans of Data: 5 things you’re doing wrong in your M&E process

- CGD, 2022: A Higher Bar or an Obstacle Course? Peer Review and Organizational Decision-Making in an International Development Bureaucracy

- Sustaining the M&E system

- IDEV: Building supply and demand for evaluation in Africa Vol. 1

- World Bank: Incentives Incentives refer to, “a particular form of payment which is intended to achieve some specific change in behaviour. Incentives come in a variety of forms, and can be either monetary or non-monetary.” for M&E - how to build demand

-

Integrating surveillance into a national plan is important for ensuring institutional capacity meets essential health functions and operations - for example through a public health service mandate and an agency to carry out specific public health functions.

Key activities

National level

- Regularly assess the national surveillance system, and develop and implement national action plans to improve the core functions of surveillance. Regularly evaluate or test national surveillance procedures, plans, or strategies (either through simulations or real health threats) to ensure continuous operational capacity. 3435

- The national plan should include elements relevant to surveillance:

- Plans for developing or enhancing event-based and syndromic surveillance. Users can refer to the WHO guidance on implementation in national legislation for additional support in facilitating surveillance and response activities that meet International Health Regulation obligations. Policy and legislation should also promote investment in infrastructure that support the functions of event-based and syndromic surveillance systems, such as electronic information systems and modernized laboratories and clinics. 3637

- Public health emergency response plan and strategies for health emergency and disaster risk management. Countries should develop procedures, plans, or strategies to activate responses to public health emergencies at a local level and to elevate to higher levels of response, as needed. This response plan should include a strategy for multi-hazard approaches, protocols for the maintenance of essential health services during response and restoration efforts, and a focus on ethics and rights-based approaches. 3839 Find more information in the resilient facilities & services module.

- Systems for sending and receiving medical countermeasures and health personnel during a public health emergency. Medical countermeasures are products that can be used for population treatment and prevention in a public health emergency, including biological products, drugs, and devices. Find more information in the Medical Countermeasures and Personnel Deployment Indicator of the WHO’s Joint External Evaluation Tool: International Health Regulations (2005). 4041

- Rapid response to and systematic monitoring of a comprehensive spectrum of health threats and diseases. Countries’ surveillance strategies may differ between the local, regional, and national levels. Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. systems that engage multiple strategies will require coordination among the different health authorities at multiple levels of the health system. 42 Find more information on developing a detailed plan of action for surveillance and response systems in the WHO’s guide to monitoring and evaluating communicable disease surveillance and response systems here and on the different types of surveillance strategies here. 4344 In addition, learn more about how to harmonize and coordinate surveillance systems with existing HIS and M&E systems in the action “collect more and better data on population health needs”.

Related elements

Relevant tools & resources

- Milken Institute, 2022: A global early warning system for pandemics: a blueprint for coordination

- WHO, 2022: Compendium of resources on surveillance in emergencies

- World Bank, 2021: Frontline: Preparing healthcare systems for shocks from disasters to pandemics

- WHO AFRO, 2019: Technical Guidelines for Integrated Disease Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. and Response in the African Region: Third edition

- Groseclose et al., 2017: Public Health Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. Systems: Recent Advances in Their Use and Evaluation

- WHO, 2017: Health emergency interim guidelines: a WHO guideline development framework and toolkit

- WHO, 2016: Joint external evaluation tool: International Health Regulations (2005)

- LHSTM, 2009: The use of epidemiological tools in conflict-affected populations: open-access educational resources for policy-makers

- WHO, 2006: Communicable disease surveillance and response systems: a guide to monitoring and evaluating

- DCP2, 2006: Public Health Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. : A Tool for Targeting and Monitoring Interventions (chapter 53)

- WHO AFRO: SORMAS ( Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. Outbreak Response Management and Analysis System)

-

Stakeholders must have systems in place to develop innovative ways of dealing with public health problems. However, mechanisms that allow countries to develop sustainable, locally-led solutions to problems, including via public health and health policy and systems research, are often underfunded and/or not well-linked to policy-making efforts. 1545 Furthermore, researchers from LMICs are poorly represented and innovation capacity tends to be low in these countries due to resource and governance constraints. Thus, improving a country’s research and innovation capacity will be an important force for economic growth and better health and policy outcomes. 4546474849

Key activities

- Assess a county’s capacity for innovation: Potential indicators a country might use to assess its innovation capacity include: investment in innovation (including human, material, and technical resources for innovations), technological infrastructure for innovation (such as internet usage for health), the sources for soliciting ideas for innovation (including user-driven and open innovation), the culture for innovation, human capital and education (i.e. tertiary education), technology transfer and participation in globalization, and gender equity.

- Cultivate a culture of innovation and learning: Organizations or institutions should strive to create a culture that readily identifies and implements innovations, taking into account the norms and values of a given context. Seven key dimensions of culture that distinguish highly innovative organizations include risk-taking, resources (in the form of time and money), knowledge, strategic goals, rewards, tools ( that support innovation), and relationships (people are exposed to a diverse range of thinking and people). 50

- Promote PHC-oriented research & development: To support the adoption and creation of innovations that support the goals of high-quality PHC for all, it is important to establish norms and values that fulfil the values of PHC such as inclusiveness and effectiveness. 51 In addition, to sustain these innovations and improve future public health interventions and programs, it is critical to ensure adequate funding and buy-in for public health and health systems and policy research. 849

- Implement mechanisms for recognizing, evaluating, and scaling innovations:

- Recognize: develop/implement tools, technologies, &/or processes that allow innovators to recognize where opportunities for innovation and learning exist. Examples include technology databases; research and utility models from health and non-health industries; publications; local and international universities and research institutes; and evidence from the field, among others. 52

- Evaluate: use M&E systems to track the progress and performance of innovations and take corrective action, as needed. If not already in place, develop standards and criteria for evaluating the “success” of innovations via a transparent, participatory process. 53 Link/align the results of the evaluation with future priority-setting exercises.

- Scale: throughout the evaluation process, identify “successful” innovations to scale based on their value and impact. If not in place, identify which factors/criteria qualify an intervention for scale. Factors/criteria may include: the target population or organization's receptiveness to change; access barriers (financial and geographic); ease of use; quality; convenience; and acceptability will influence the strategy for scale. 5455 Before scaling an innovation, evaluators should ensure it has undergone multiple iterations at the pilot stage to determine its value, performance, and application to the context/level/location in which it will be implemented, including whether the environment the innovation will be implemented in is sufficiently ready for change.

- Strengthen institutional capacity and stakeholder buy-in: While countries will likely have their own unique methods/mechanisms/processes that lead to different outputs, scaling up innovations require initiatives built around diverse stakeholder participation, financially sustainable institutions, and supportive governance structures that support their integration into the health system. Examples include: 55

- Awareness: provide information to policymakers, the public, and the media that stimulates innovation and learning.

- Performance: measure progress and results of changes that have been implemented against public policy objectives and the market factors (i.e. supply and demand)

- Signalling and Monitoring: call attention to important innovation trends and growth opportunities.

- Accountability and evaluation: support research and development budgets and innovation policies, in addition to compliance with regulatory structures and public interests.

- Consensus building: develop and implement more effective innovation policies and strategies that strengthen a country’s national innovation capacity.

Related elements

- Policy & leadership

- Multi-sectoral approach

- Funding & allocation of resources

- Information & technology

- Population health management

- Management of services

Relevant tools & resources

- Fundamentals

- IHI: Model for improvement

- IHI: Quality Improvement Essentials Toolkit

- USAID and Momentum: Toolkit for adaptive learning in projects & programs

- EPIS: Implementation framework & toolkit

- CFIR Research Team-Center for Clinical Management Research, 2022: The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- Alliance for health policy and systems research, 2021: What is health policy and systems research?

- Alliance for health policy and systems research, 2021: Learning health systems: pathways to progress

- WHO, 2022: Compendium of resources on health research

- IDIA, 2021: Framework, tools, and reports on strengthening and scaling innovation

- Measuring innovation capacity & building a culture of innovation and learning

- Policy innovation research unit: Developing a Global Healthcare Innovation Index

- Harvard Business Review: What is organizational culture? And why should we care?

- NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement: Creating the culture for innovation: a practical guide for leaders

- WHO: OpenWHO (web-based knowledge-transfer platform)

- Recognizing, evaluating, and scaling innovations

- LEAD innovation: identification of innovation potential - 6 important triggers for innovation

- WHO: How do we ensure that innovation in health service delivery and organization is implemented, sustained and spread?

- Stanford Social Innovation Review: Innovate and Scale: A Tough Balancing Act

- R4D: Scaling Innovations

- IHI: Science of improvement - implementing changes

- IHI: Science of improvement - spreading changes

- IHI: A Framework for Spread: From Local Improvements to System-Wide Change

- NCMMT, 2022: Implementing Knowledge Translation Strategies in Public Health

- WHO, 2010: Nine steps for developing a scaling-up strategy

- Strengthening institutional capacity for innovation

- WHO: Social innovation in health: case studies and lessons learned from low- and middle-income countries

- OECD: Innovation policies for inclusive development

- IHI: The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance

- World Bank, 2017: The innovation paradox: developing-country capabilities and the unrealized promise of technological catch-up

-

Encouraging broader social participation in decision-making and evaluation processes (including community-based representation) helps to strengthen accountability across sectors and forge collaborative partnerships for more equitable and sustainable initiatives. 56

Key questions & activities

- Understand who, and to what extent, are involved in decision-making processes. It is important to engage a diverse array of stakeholders in priority-setting, M&E, and innovation and learning processes. Implicit in this is the existence of systems for multisectoral and community engagement at national and sub-national levels. If stakeholder engagement does not occur or is not occurring for all priority setting exercises, you might consider looking at recent examples of priority setting and M&E in your country:

- Are stakeholders’ roles & responsibilities clearly defined and communicated?

- Are processes for identifying, communicating with, and convening stakeholders in place? What processes are in place to engage and coordinate the interests and actions of stakeholders from diverse contexts (including the private and non-health sectors)?

- Are these processes transparent, inclusive, and consistent?

- Are engagements occurring at regular, predefined intervals and when necessary, on an ad-hoc basis?

- If not, are gaps due to problems with social accountability mechanisms, communication networks, policies, or other factors?

- See the sub-action on engaging and empowering patients, families, and communities (take action section) for a comprehensive list of activities that countries can implement.

Related elements

- Understand who, and to what extent, are involved in decision-making processes. It is important to engage a diverse array of stakeholders in priority-setting, M&E, and innovation and learning processes. Implicit in this is the existence of systems for multisectoral and community engagement at national and sub-national levels. If stakeholder engagement does not occur or is not occurring for all priority setting exercises, you might consider looking at recent examples of priority setting and M&E in your country:

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Understanding and identifying the drivers of health systems performance--referred to here as “related elements”--is an integral part of improvement efforts. We define related elements as the factors in a health system that have the potential to impact, whether positive or negative, a country's ability to adjust to population health needs. Explore this section to learn about the different elements in a health system that should be improved or prioritized to maximize the success of actions described in the “take action” section.

While there are many complex factors in a health system that can impact adjustment to population health needs, some of the major drivers are listed below:

- Policies, leadership, & financing

-

Strong governance structures, such as PHC policies, leadership commitment, and dedicated budgets, help to establish and enforce participatory priority setting, M&E, and innovation and learning mechanisms necessary for adjustment to population health needs. Regulatory structures, such as internal audits or reviews also help to ensure that these mechanisms consistently generate high-quality, reliable information that is being used as intended. From a financing perspective, understanding the financial capacity for PHC funding and cost-effectiveness measures helps to inform priority setting including resource distribution.

Learn more in the policy & leadership and financing modules.

- Multi-sectoral approach

-

Priority-setting, M&E, and innovation and learning are dynamic processes that rely on shared learning and input from stakeholders across all levels of the system. Encouraging broader social participation in the decision-making process (including community-based representation and a multisectoral approach) helps to strengthen accountability across sectors and forge collaborative partnerships for equitable and sustainable initiatives.

- Information & technology

-

Priority setting and M&E rely on the use of diverse sources of data (including health and burden of disease information, service delivery evaluations, and cost-effectiveness assessments and surveillance data) as well as stakeholder input to prioritize the most appropriate programs and interventions to improve population health for all. Up-to-date health information also helps to guide innovation and learning efforts and is essential for monitoring, evaluating, and scaling innovations.

- Management of services & population health

-

Several facility- and community- level mechanisms can help to reinforce national-level priority setting, M&E, and innovation and learning efforts:

- Community engagement: Priority setting exercises at the national level should both inform and be informed by local priorities. Additionally, stakeholder engagement from the local level is an important tool for making innovations (and the evaluations of health strategies and innovations) responsive to existing and emerging social concerns and priorities relevant to the sub-national level.

- Facility leadership and performance management: Effective management supports the adoption and adaptation of novel and ongoing quality improvement initiatives for innovation and learning activities at the facility level. Performance measurement and management also enable the monitoring and evaluation of innovations at the facility level.

- Systems for improving quality improvement: Quality management infrastructure, a component of organisation of services, creates and enables a systems environment for improvement, which is part and parcel of building a culture of innovation and learning.

Learn more in the population health management and management of services modules.

- Person-centredness

-

Understanding health sector priorities and performance from the perspective of the patient are critical to designing national health strategies and innovations that meet patient needs and ultimately enable the design of person-centred health systems.

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Countries seeking to improve their ability to adjust to population health needs can pursue a wide array of potential improvement pathways. The short case studies below highlight promising and innovative approaches that countries around the world have taken to improve.

PHCPI-authored cases were developed via an examination of the existing literature. Some also feature key learnings from in-country experts.

- East Asia & the Pacific

- Europe & Central Asia

- Latin America & the Caribbean

- Middle East & North Africa

- North America

- South Asia

-

- Afghanistan: Priority setting for UHC in a conflict setting

- India: Enabling data-driven decision-making in urban local

- India: A decentralized approach to improving community engagement in priority setting

- India: Revamping of Public Health Surveillance System

- Kerala, India: Decentralized governance and community engagement to strengthen primary care.

- Sub-Saharan Africa

-

- Ghana: Creating an evidence-based action plan for strong PHC

- Ghana: Translating Research into Practice to Ensure Community Engagement for Successful Primary Health Care Service Delivery: The Case of CHPS in Ghana

- Malawi and Kenya: Community health worker-based surveillance in resource-constrained contexts

- Mozambique: Strengthening local and national information systems during COVID-19

- Multiple countries: Building supply and demand for evaluation in Africa Vol. 1

- Multiple countries: Challenges with the implementation of an Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) system: a systematic review of the lessons learned

- Multiple countries: Governance of health research in four eastern and southern African countries

- Multiple countries: Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) strategy: current status, challenges and perspectives for the future in Africa

- Multiple countries: Integrated disease surveillance and response

- Multiple countries: The community of practice health delivery: strengthening knowledge sharing to accelerate PHC improvement in Sub-Saharan Africa

- South Africa: Integrating health technology assessment and the right to health: a qualitative content analysis of procedural values in South African judicial decisions

- Tanzania: Participatory decision-making in priority setting

- Multiple regions

-

- Building national innovation capacity

- Learning health systems: pathways to progress

- Measuring what matters: case studies on data innovations for strengthening PHC

- Reverse innovation in global health systems: learning from low-income countries

- Social innovation in health: case studies and lessons learned from LMICs

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Building consensus on what adjustment to population health needs is and key strategies to fix gaps is an important step in the improvement process.

Below, we define some of the core characteristics of adjustment to population health needs in greater detail, with the exception of public health surveillance, which is covered in the Information and Technology module.

-

Priority setting The process of making decisions about how best to allocate limited resources to improve population health. is the process of making decisions about how best to allocate limited resources to improve population health. It involves the use of information collected from surveillance systems and other health information systems to set, implement, and adjust priorities over time. For this reason, a well-functioning health information system is also a critical input to the priority setting process. If data generated from these systems is incomplete or unreliable, it may lead decision-makers to make false conclusions about the extent of health problems and the effectiveness of strategies. 40575859

Effective priority setting also involves the use of an evidence-informed deliberative process (EDP). EDPs provide a structured process by which diverse stakeholders identify explicit criteria for priority setting, interpret evidence, and deliberate on recommendations and decisions based on their opinions, needs, and interests. When rooted in a strong multisectoral approach (whereby diverse stakeholders are involved and held accountable to citizen interests), EDPs add both scientific and social credibility to the decision-making process. 405758 596061

Priority setting The process of making decisions about how best to allocate limited resources to improve population health. may occur at all levels of the health system. However, the information here is specific to national and sub-national priority setting. More information on priority setting at the community level can be found in the population health management module.

Priorities are evidence-based

Priority setting The process of making decisions about how best to allocate limited resources to improve population health. relies on the use of diverse sources of data (including health and burden of disease information, service delivery evaluations, and cost-effectiveness assessments) as well as stakeholder input to prioritize the most appropriate programs and interventions and inform resource allocation. 575859

Priority setting The process of making decisions about how best to allocate limited resources to improve population health. exercises should therefore start with an in-depth situation analysis of the health sector to determine existing and emerging needs. 2 A situation analysis identifies the strengths and weaknesses of the health system and is a key initial step in the development of different elements of the national health plan, including the strategic directions and identification of priority diseases and interventions. 62 The situation analysis must generate a sufficient evidence base to ensure that stakeholders have access to quality and diverse information needed to make informed decisions consistent with the needs and values of the population. 58 While the situation analysis can happen at any level of the health system and on varying themes and scopes, such as health financing or workforce, 262 this module focuses on an overall health sector situation analysis for system-wide priority setting.

According to the World Health Organization, a well-facilitated situation analysis should be participatory and inclusive, analytical, relevant, comprehensive, and evidence-based and is separated into three distinct streams of analysis: 62

- Health data “In public health, “data” usually refers to statistics reported from health care facilities, survey data or data collected through observational studies. Distinctions can be made between routinely reported data and data that are collected at certain times or over a specific period of time as part of a special study or survey. Both routine and non-routine data, as well as data from research systems, are required and contribute to a fuller picture of any given public health issue.” - Analyses of health data from all levels of the health system - national, regional, and local - including trends and developments over time, provide information on both the health needs of the population and the current performance of the health system in meeting those needs. Analysts involved in examining health data should include technical experts trained to analyze and interpret data and non-technical experts familiar with health sector activities. Examples of data sources include population health surveys, HMIS, CRVS, facility assessments, patient-reported outcomes, and surveillance system reports.

- Activity and budget - An analysis of the health sector budget and the implementation of health sector activities should assess whether the budgets allocated in the health sector and the policies, strategies, or plans adopted into the national health plan reflect the broader national health plan objectives, including whether activities are sufficiently funded and able to be implemented as per the planned activities and budget. Examples of data sources include Ministry of Health and Ministry of Finance routine financial reports, national health accounts, public expenditure data, performance reports, and facility assessments.

- Effectiveness Effectiveness refers to care that is evidenced-based and adheres to established standards and the extent to which a specific intervention, procedure, regimen or service does what it is intended to do for a specified population when deployed in everyday circumstances. of national health plan activities - This analysis should assess the strengths and weaknesses of different elements in the health system, including programs, sub-policies, and strategies, focusing on whether those elements have achieved the expected results and what changes may need to occur in order to reach higher levels of effectiveness. While the first two streams of analysis rely heavily on technical expertise, this analysis is grounded in a participatory dialogue that considers both the opinions of experts as well as those using the health system on a daily basis - the service providers and the population themselves.

The situation analysis should be conducted by a core team of working groups comprised of relevant experts and stakeholders who have a sufficient understanding of the issue and are representative of all the categories of the population. 62 More information on establishing working groups, identifying the expertise required for situation analysis, and sequencing of work can be found in the WHO chapter on situation analysis of the health sector.

Priorities are based on explicit criteria

The national health planning process always includes priorities. These priorities may be explicitly set or ad hoc. Effective priority setting is explicit, meaning it involves a transparent discussion among diverse stakeholders who determine priorities based on a joint examination of the evidence and explicit criteria. Priority setting The process of making decisions about how best to allocate limited resources to improve population health. that is ad hoc does not encourage accountability and is prone to biases or special interests. The WHO recommends the following steps for an explicit priority setting process: 263

- Adopt a clear mandate for the priority setting exercise

- Define the scope of the priority setting exercise and who will play what role

- Establish a steering body and a process management group

- Decide on approach, methods, and tools

- Develop a work plan for priority setting and assure the availability of the necessary resources

- Develop an effective communication strategy

- Inform the public about priority setting and engage internal/external stakeholders

- Organize the data collection, analysis, and consultation/deliberation processes

- Identify or develop a scoring system

- Adopt a plan for monitoring and evaluating the priority-setting exercise

- Collate and analyze the scores

- Present the provisional results for discussion; adjust if necessary

- Distribute the priority list to stakeholders

- Assure the formal validation of recommendations of the priority setting outcome

- Plan and organize the follow-up of the priority setting, i.e. the decision-making steps

- Evaluate the priority setting exercise

This process should result in a set of priorities, ranked by what is considered to be the most important based on the established criteria. Criteria are a set of measures that stakeholders use to weigh and determine which health problems, challenges, and solutions should be made a priority. These criteria should be defined before starting the priority setting process and be the basis for final priority setting decisions. In order to make high-quality PHC a priority, stakeholders need to define the principles that drive high-quality PHC (such as equity, efficiency, and sustainability) and set priorities for their health system based on these principles. 64

These principles will inform how stakeholders evaluate criteria relative to each other when considering what is politically feasible, affordable, and technically possible. 5765 The WHO suggests a non-comprehensive list of five criteria that can be used to set priorities in the health sector. These include:

- The burden of disease: The burden of disease is a quantitative, time-based measure that combines years of life lost due to premature mortality and years of life lost due to time lived in states of sub-optimal health (i.e. injury, disease).

- The effectiveness of the intervention: This criterion evaluates how well the identified health issue can be addressed (clinically or practically) by the given intervention, including if the intervention is applicable and cost-effective for the local context.

- Cost of the intervention: This criterion considers the cost of an intervention in terms of affordability and efficiency. It is important to consider the absolute and relative costs to the health sector, target community, and individuals. The cost of an intervention must be both economically feasible and sustainable.

- Acceptability of the intervention: This criterion refers to whether the target community or population accepts the chosen health intervention, taking into account the social and cultural norms as well as the willingness of providers or other health authorities to carry out the intervention (i.e. risk aversion, resistance to change, perceived value). This criterion strongly relates to the applicability and feasibility elements of the effectiveness criteria; both require contextual knowledge to evaluate the intervention.

- Fairness: Fairness is a value judgment made collectively by governments and society based on the principles of equality and equity. The fairness criteria are essential to make well-informed judgements about tradeoffs on the importance of a health need and the effectiveness of an intervention. It also influences how much weight to give to the cost of a solution. For example, it might be important to prioritize the health problems of a specific at-risk or marginalized segment of the population, even if the intervention is not particularly cost-effective. An evaluation of fairness can help direct resources to marginalized populations, even when the intervention is not the most cost-effective solution.

Often, stakeholders will have to make trade-offs between different criteria; for example, stakeholders may consider both equity and cost-effectiveness in the evaluation of a given health intervention and find that the intervention that is the most equitable might not be the most cost-effective. The weight given to different criteria is ultimately a political decision shaped by the country's context, including values, principles, and economic and political environment. 57

While the above criteria are a strong starting point for priority-setting conversations, new criteria may need to be added or adapted based on contextual factors, such as the epidemiological and demographic profile of the country, the health system structure, and political and financial capital. 5766 Accordingly, local needs and norms will influence the relative weight attached to these different criteria. The analyses of these criteria will depend on both the quality of the data and information available - including information on the implementation of interventions.

Priorities are accountable to diverse stakeholder interests

Effective priority setting addresses the differing interests and motivations of stakeholders through a clear process focused on the use of evidence, transparency, and participation to identify the most appropriate programs and interventions to address population health needs. 57

Priority setting The process of making decisions about how best to allocate limited resources to improve population health. is a shared and multisectoral responsibility that relies on participatory and inclusive stakeholder engagement, including both people who will be affected by decision-making and people who can influence the implementation of the selected priorities during the priority-setting process. 5767 Stakeholder engagement plays an important role in priority setting because it ensures that priorities reflect population needs and that the interventions and programs selected are acceptable, appropriate, and desired. 14 Stakeholder engagement should be systematic, meaning the processes for identifying, communicating with, and convening stakeholders are transparent and consistent, with engagements occurring at regular, predefined intervals as well as on an ad-hoc basis, as necessary. Opportunities should be made for citizens to play an active role in shaping the priority-setting agenda, including through citizen consultations and community leader involvement in decision-making processes.

The World Health Organization identifies three categories of stakeholders that should be involved in priority setting: 5768

- Government: The role of the government is to plan, initiate, coordinate, and oversee the priority-setting process within and across stakeholders and organizations. The way in which government stakeholders coordinate the priority setting process and who specifically will engage depends on the economic and political environment of the health system. For example, decentralized environments may need to collaborate more with local governments and providers whereas highly aid-dependent contexts may involve more collaboration with development partners. High-level actors may include policy-makers and planners in the Ministry of Health and other ministries as well as administrative and health authorities at decentralized levels.

- Providers: Service delivery providers are important stakeholders because they can offer insights into the feasibility of prioritized service delivery decisions, including balancing patients’ needs and demands with cost-effectiveness. Provider-level actors may include health professionals in both the public and non-public sectors.

- Clients/citizens: To ensure stakeholders are accountable for their decisions, citizens should be involved in determining which priorities are set as a part of a democratic process. Citizens should be well-informed in advance about the advantages and disadvantages of various options. Citizen-level actors may include citizens themselves, community representatives, and/or groups of patients. Particular attention should be given to ensuring a diverse and representative group of citizen-level actors in this process.

Stakeholders must be willing to continue participating in the process and accept priority-setting decisions, even if they disagree with the outcomes. 59 Effective stakeholder engagement relies on robust institutional frameworks for multisectoral action and social accountability strategies. 57 More information on multi-sectoral engagement and social accountability can be found on the relevant tools and resources page for priority setting.

Priorities are aligned with health sector policy, planning, & review processes

While priority setting for PHC is an integral part of improving population health for all, it must be supported by strong governance, political, and financial commitment as well as regulation and implementation capacities to achieve priority setting goals. 64

After the priority setting process, relevant stakeholders will need to translate priorities into the strategic and operational plans for the health sector, followed by costing and budgeting, implementation, and finally, monitoring and evaluation (covered in the Monitoring and Evaluation deep dive). 2 Multiple tools exist to assist with the planning and implementation of health interventions set as a part of the priority process, including Partners in Health’s UHC Monitoring and Planning tool. 6970

More information on resources allocation and planning can be found in the WHO’s chapters on estimating cost implications of a NHPSP, budgeting for health, monitoring, evaluation and review of NHPSP, and strategizing for health at sub-national level.

-

Monitoring & evaluation (M&E) is a process by which stakeholders collect, measure, and use data to assess and maximize the impact of projects, programs, or social initiatives over time. It seeks to answer the question--is the project, program, &/or initiative going according to plan? If not, why? And what changes are needed to maximize impact? As opposed to surveillance, M&E is a more “passive” process, whereby the data collected on any disease or intervention is monitored on a weekly, monthly, quarterly, or even yearly basis depending on the project, program, or initiative. It involves two interrelated processes: 432717273

- Monitoring, which is an ongoing process of collecting and analyzing data on specified indicators to track and measure how a change is happening. This data is used to plan, monitor, and improve projects, programs, &/or initiative activities.