|

|

|

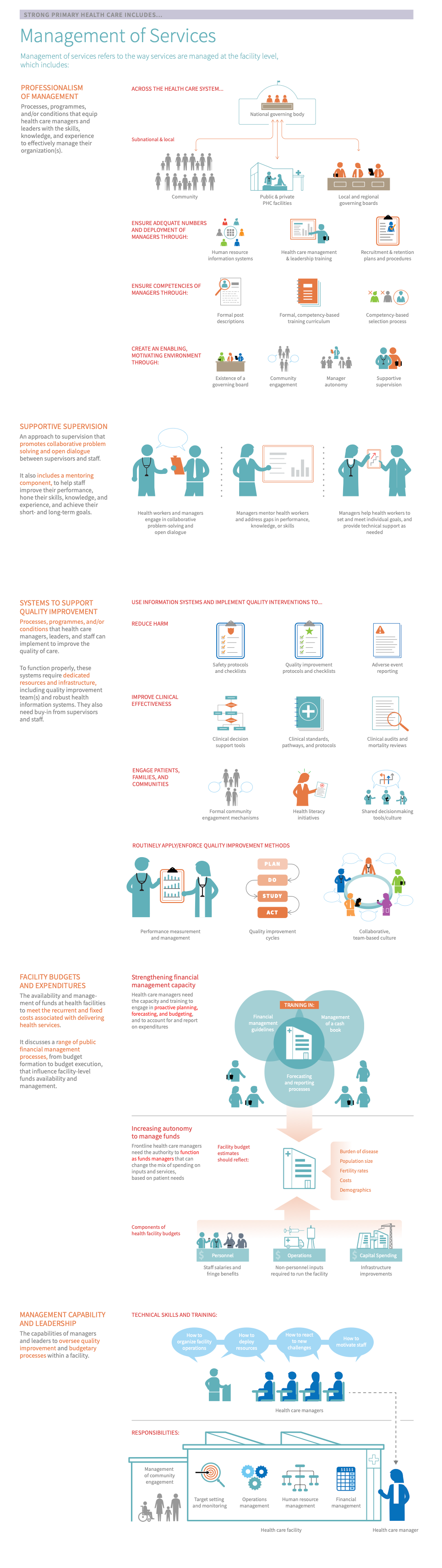

Management of Services refers to the way services are managed at the facility level, which includes:1234567

-

Professionalism of management means that “conditions are in place nationally (and subnationally) to ensure professionalized management and leadership in a health care organization. This is achieved by ensuring adequate numbers, competencies and deployment of managers throughout the health system, and creating an enabling environment that contributes to managers’ motivation and enables them to perform well.” Professionalism of management is often measured by the number, competence, and motivation of managers, such as via posting and transfer policies, supportive supervision, and formal training, among others.

Well-managed facilities must be supported by national and subnational systems that promote the professionalization of managers through competency-based training, professional support structures, and appropriate autonomy for them to carry out their responsibilities.

Quality improvement the action of every person working to implement iterative, measurable changes, to make health services more effective, safe, and people-centred. systems at all levels of the health system - from national policies to facility-level information systems and improvement processes - promote continual improvement and routine use of data to evaluate progress towards goals.

- Systems to support quality improvement, which refers to the use of information systems and quality improvement methods/practices (i.e. PDSA cycles) to make health services more effective, safe, and people-centered via iterative, measurable changes. It includes the routine collection and use of information systems to establish targets, monitor progress, and implement ongoing quality improvement initiatives to address identified gaps.

- Facility

Budget

A document that outlines forecasted revenue and planned expenditure for an entity (government, subnational unit, or health facility) over a defined period of time. Budgets indicate how funds are meant to be allocated to achieve certain objectives.

s and expenditures, which address the availability and management of funds at health facilities to meet the recurrent and fixed costs associated with delivering health services. It discusses a range of

Public financial management

The rules and regulations established to ensure transparent, effective, accountable management of public (government) finances. PFM includes all phases of the budget cycle, including the preparation of the budget, budget execution, internal control and audit, procurement, monitoring and reporting arrangements, and external audit.

processes, from budget formation to budget execution, that influence facility-level funds availability and management. It often includes the following attributes:

Line-item funds

Funding amounts from government source for specific types of regular expenses, such as supplies, equipment, staff, or income, such as from service-specific fees

, billing/insurance/other patient financial coverage

Tracked-use expenses

Refers most often to reimbursements by government or private insurance mechanisms for services provided to patients.

,

Internally generated funds

Funds are generated at and by the facility, most often from user fees or other fees that are collected at the point of care.

from user fees or other fees collected at the point of care, flexibility to use and/or re-allocate funds across budgetary lines to fit evolving financial needs and to retain fees collected at service level, and the use of a comprehensive annual budget to engage in a

Systematic forecasting exercise

Projecting expected costs and income for a future period of time, based on past data, to enable strategic planning.

. - Management capability and leadership, which refers to the capabilities of managers and leaders to oversee quality improvement and budgetary processes within a facility. Leaders should also have relevant skills related to coordination of operations, external/consumer relations, target setting, and human resources. Strong leaders must have or develop particular competencies and personality traits to engage the workforce and manage effectively. Competencies The observable abilities—including knowledge, skills, and behaviours—of individual health workers that relate to specific work activities. Competencies are durable, trainable, and measurable. can be defined as the combination of motive, trait, skill, self-image, social role, and body of relevant knowledge or the capability of managers to oversee, support, and enforce these processes.

- Supportive supervision is a component of performance measurement and management. It is characterized by collaborative problem solving and open dialogue. Supervision routinely includes mentoring to address gaps in performance, knowledge, and skills and setting individual goals and reviewing progress towards their achievement.

Management of services requires a multifaceted approach with strong linkages to district management and national strategic direction. It is relevant to many different parts of the health system, including the private and public sectors; health facilities, district health offices and central ministries. It also involves support- and information systems related to pharmaceuticals, finances, and human resources. Key activities within management of services span organizational aspects with focused attention to clinical improvement, reducing harm, and engagement with patients, families and communities.1

It is important to note that the term “manager” may differ between contexts and there is not a standardized definition across all settings. Here we use it to refer to someone in a health facility who spends a significant amount of their time in a managerial role which may involve: planning, implementing, and evaluating volume and coverage of services, reviewing and managing resources such as staff, budgets, drugs, etc, and management of relationships with partners, including patients.1

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Read on to learn how to use country data to:

- Make informed decisions about where to spend time and resources

- Track progress and communicate these updates to constituents or funders

- Gain new insights into long-standing trends or surprising gaps

Countries can measure their performance using the Vital Signs Profile (VSP). The VSP is a first-of-its-kind tool that helps stakeholders quickly diagnose the main strengths and weaknesses of primary health care in their country in a rigorous, standardized way. The second-generation Vital Signs Profile measures the essential elements of PHC across three main pillars: Capacity, Performance, and Impact. Management of services is measured in the Management of Services and Population Health domain of the VSP (Capacity Pillar).

If a country does not have a VSP, it can begin to focus improvement efforts using the subsections below, which address:

- Key indications

-

If your country does not have a VSP, the indications below may help you to start to identify whether the management of services is a relevant area for improvement:

- Underuse and/or reporting of quality improvement data and system: Data is not being routinely collected, analyzed and used to drive decision making, performance monitoring, and quality improvement at the facility or health system level. For example:

- There is a lack of use of established performance indicators for PHC in primary care facilities/primary health care networks.

- There is little to no routine monitoring of these performance indicators for PHC in primary care facilities/primary health care networks.

- There is an absence of documented quality improvement work linked to underperforming areas in primary care facilities/primary health care networks.

- Information systems are poorly integrated into facility operations, for example:

- Staff are not appropriately trained or equipped with the requisite infrastructure to use information systems as intended.

- Existing information systems fit poorly into existing staff workflow and the goals of information systems use are poorly communicated to staff.

- Data resulting from Information Systems are missing, incomplete, or of poor quality.

- Inefficient facility operations: Day-to-day facility operations, including human resources, operations, financial, and performance management, are inefficient or poorly functioning. For example, there may be issues with provider motivation and absenteeism and/or routine financial planning

- Poor culture of learning/improvement: Facility leaders inconsistently use systems to collect and monitor feedback and performance, such as community advisory boards or routine systems for monitoring provider performance, and/or are not responsive to this feedback

- Gaps in the professionalism of management: Little to no facility managers receive official management training and routine feedback on their management capabilities and performance.

- Underuse and/or reporting of quality improvement data and system: Data is not being routinely collected, analyzed and used to drive decision making, performance monitoring, and quality improvement at the facility or health system level. For example:

- Key outcomes and impact

-

Countries that strengthen their management of services may achieve the following benefits or outcomes16:

- Safe, person-centred, effective care: Management of services is important for ensuring that PHC facilities use funds in the way they are intended and that they provide safe, high-quality services to the communities they serve. Management of services also helps to ensure that facility-based data is collected and used to make health services more effective, safe, and people-centred.

- More efficient, cost-effective care: Furthermore, management of services ensures systems are in place to identify and improve on any identified gaps in service delivery and to proactively plan for future activities and expenditures, ultimately helping to improve the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of services. Well-managed facilities also utilize these data to implement needed changes to facility infrastructure, amenities, and service delivery processes, eventually leading to improved facility outputs and outcomes.

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Explore this page for a curated list of actions to improve the management of services, which embark on:

- An explanation of why the action is important for the management of services

- Descriptions of activities or interventions countries can implement to improve the management of services

- Descriptions of the key drivers in the health system that should be improved to maximise the success or impact of actions

- Relevant tools and resources

Key actions:

-

Well-managed services must have an appropriate supply of trained, competent, and motivated managers who have the autonomy to carry out management responsibilities. Professionalization of management capacity responsibilities ranges from the national to facility level and involves a variety of stakeholders.

Key Activities

National level

- Establish a nationally-accessible information system that provides information about filled posts, national and subnational issues such as retention, and stores information on the qualifications and training records of managers

- Provide formalized management posts in the human resources health information system that provide clarity about the roles and degree of authority of managers at all levels and job descriptions

- Develop a national competency framework for managers that that identifies the values, attributes, and skills necessary for managers

- Use national competency frameworks to identify and plan training programs for managers that are appropriately aligned with their responsibilities and integrated into their work

- Ministry of Health should work with donors to ensure that requests of managers are harmonized and not competing with one another

- Provide managers with local control and autonomy to make decisions relevant to their context

Facility level

- Ensure that facility leaders give facility managers autonomy to manage services and providers to the full extent of their training and competencies

- Provide supportive supervision to facility managers to help them build the skills necessary to manage effectively and identify gaps in their training or knowledge

- Prioritize training for managers and ensure that there will be appropriate coverage for their tasks if they need to attend relevant trainings when they are scheduled to be in the facility

Related elements

- Medicines and supplies

- Health workforce

- Information and technology

- Service availability and readiness

Relevant tools & resources

- The Handbook for Improving Health Services developed by Management Sciences for Health as well as the NHS Leadership Qualities Framework are examples of competency frameworks that can be used to evaluate managers and identify where they can build competencies through training or coaching

- Towards better leadership and management in health - this report was the result of an international consultation on strengthening leadership and management in low-income countries.

- D9.2 Report on reflection and learning on the use of a scale-up framework and strategy for a management strengthening intervention in Ghana, Tanzania, and Uganda

-

Improving the quality of care involves three interlinked concepts: quality planning, quality control, and quality improvement. 34041

Quality planning Includes aims, processes, and goals needed to create an environment for continuous improvement. includes aims, processes, and goals needed to create an environment for continuous improvement.

Quality control Entails monitoring established processes to ensure their functionality. entails monitoring established processes to ensure their functionality.

Quality improvement the action of every person working to implement iterative, measurable changes, to make health services more effective, safe, and people-centred. is the action of every person working to implement iterative, measurable changes, to make health services more effective, safe, and people-centred.

This action provides guidance on the steps countries can take to make health services more effective, safe, and people-centred via careful planning and iterative, measurable changes. This includes the implementation of initiatives designed to reduce harm, improve the clinical effectiveness of care, and engage patients, families and communities. Because quality care requires careful planning and buy-in at all levels of the health system, it begins with guidance on how to create an enabling environment for quality.404243

Key Activities

National level

Establish a national commitment to quality 404142

See page 13 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance

Develop a national strategic direction on quality and safety and update the national quality policy strategy, and/or plan at least every five years 404142

See pages 14 - 17 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance. Also, see Annex 2 of the guide for a list of questions that should be considered when planning for quality in a health system.

Select and prioritise a set of quality interventions, including: 40414244

Interventions to create an enabling systems environment (i.e. registration and licensing, external evaluation and accreditation, clinical governance, public reporting and benchmarking, training and supervision of the health workforce)

Interventions to reduce harm (i.e. safety protocols and checklists, quality improvement protocols and checklists, systems for adverse event reporting)

Interventions to improve the clinical effectiveness of care (i.e. standardised clinical forms and decision support tools, context-appropriate clinical standards, pathways, and protocols, clinical audits and mortality reviews)

Interventions to engage patients, families, and communities (i.e. shared decision-making tools, services for health literacy and self-care, formalized community engagement mechanisms)

Develop a pragmatic quality measurement framework42

See page 17 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance

Develop an operational plan and resourcing strategy to ensure the national direction on quality is translated into action. Some of the critical resource considerations include: 404142

Time spent by clinicians and providers in training, records departments, and discussing standards, measurements, and action plans is time they are not spending in clinics.

Data, information, and guidance: Clinical and management staff need access to standards, practical guidance on tested quality improvement methods, and examples of results – these must be gathered and developed for local use.

Funding: The cost of staff time, and how to best use it, is a critical resource question at all times. Direct costs of quality improvement programs include quality support staff, training, data collection and access to information.

See pages 17 - 18 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance

Establish a quality directorate/department/unit to take forward the development and operationalization of the national direction on quality.40

To aid in this step:

This directorate should intentionally work across different health sector institutions and stakeholders outside the government such as health professional associations have the potential to achieve buy-in as well as gain additional resources for developing and implementing regulation.10

They should also coordinate quality systems with national and/or local government to ensure valid standards, reliable assessments, consumer involvement, demonstrable improvement, transparency, and public access to quality criteria, procedures, and results3

Establish well-designed health information and monitoring & evaluation systems that routinely collect and publish data on quality health systems at the national, subnational, and local levels, as well as external assessment through peer review and accreditation.404142

See action #3 in the adjustment to population health needs module for a list of activities that countries can take to strengthen their M&E systems; and a list of relevant case studies, tools, and resources

Cultivate a culture of learning on quality across the health system and embrace a continuous process.404142

Timelines of implementers and governments do not always line up – the process of institutionalizing quality management infrastructure can take as much as 5-8 years, while the people involved in the structures might change more quickly. “In using external technical assistance to set up quality systems, attention should be given to ensuring that transferred know-how becomes fully institutionalized”.3

See pages 14 - 15 of the WHO’s handbook for national quality policy and strategy for additional guidance

Subnational and/or district levels

- Commit to delivering on national quality goals and priorities42

- See page 24 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance

- Develop district-level quality structures and operational plans and update them based on learnings from health facilities and the new/emerging national strategic direction on quality (if relevant)42

- See pages 25 - 26 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance

- Orient health facilities to the district- and national level quality goals and priorities42

- See pages 25 - 26 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance

- Respond to facility needs in reaching selected aims and ensure functioning support systems for quality health services42

- See page 29 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance

- Maintain engagement with the national level on quality health services42

- See pages 26 - 29 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance

- Foster a positive environment for quality health service delivery and adapt quality interventions to district-level contexts42

- See pages 30 - 32 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance

Facility level

- Commit to district aims and identify clear facility improvement aim(s)

- See pages 40 - 41 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance

- Establish, organize and support multidisciplinary quality improvement teams & prepare for action.

- See pages 41 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance

- Conduct a situational analysis/baseline assessment to understand the current ‘state of quality' in the facility and identify gaps: A key step in improving service quality is evaluating how services and/or processes are doing and how much value they are providing to patients. There are a variety of tools and techniques that can be used to evaluate the quality of care at the facility level:

- Health facility assessments (i.e. Service Provision Assessments, Harmonized Health Facility Assessments, Service Availability and Readiness Assessments, etc.)

- Individual-level surveys (i.e. PROMs questionnaire, patient satisfaction surveys, provider satisfaction surveys)

- Other facility-specific assessments (i.e. setting and monitoring progress toward internal quality improvement targets)

- See pages 42 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance

- Adopt standards of care

- See pages 42 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance

- Identify and prepare for quality improvement activities by developing an action plan. Some activities include

- See pages 43 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance

- Undertake continuous measurement of outcomes

- See pages 44 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance

- Focus on continuous improvement – identify what works and does not work and refine action plans over time

- To aid in this step:

- Build pathways to improvement through supportive supervision, performance monitoring and measurement, and continuing professional development. To avoid duplication and fragmentation, performance monitoring that occurs at the facility level should be aligned with national and subnational monitoring and evaluation strategies/efforts.41424546

- Collect and use performance data to make decisions and improve the quality of services: to ensure that services and/or processes align with population health needs and context, it is important to continuously collect accurate, timely, and reliable population health data as a part of this process. This data, should, in turn, feed into local decision-making processes to ensure that services and/or processes align with the local population’s needs and preferences and achieve desired health outcomes. Approaches should prioritize improvements in areas with the greatest quality deficits to ensure health equity and the efficient use of resources.4247

- Cultivate a culture of learning: Primary care Primary care is “a key process in the health system that supports first-contact, accessible, continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated patient-focused care.” facilities should be designed and managed with systems in place to identify, react to, and learn from safety incidents and quality gaps. To do so, facilities must foster a culture of safety, report on errors and near misses, learn from their mistakes, and track progress towards safety and quality-related goals.4247

- See pages 45 - 46 of the WHO’s planning guide for quality health services for step-by-step guidance

- To aid in this step:

Related elements

- Policy & leadership

- Funding & allocation of resources

- Adjustment to population health needs

- Multi-sectoral approach

- Information & technology

- Organisation of services

Relevant tools & resources

- WHO, 2022: Compendium of resources on quality of care

- The Global Fund, 2022: Compendium of resources on the quality assurance of essential health products

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2022: Improvement capability self-assessment tool

- WHO, 2020: Quality health services: a planning guide

- WHO, 2020: Operational framework for primary health care - see operational lever on systems for improving quality of care (page 58)

- WHO, World Bank, and OECD, 2019: Delivering quality health services: a global imperative for universal health coverage

- WHO, 2018: Technical series on PHC - Quality in PHC

- WHO, 2018: Handbook for national quality policy and strategy: a practical approach for developing policy and strategy to improve quality of care

- PHCPI, 2017: Building a thriving primary health care system: the story of Costa Rica

- WHO, 2016: Guidelines on core components of infection prevention and control programmes at the national and acute health care facility level

-

Well-managed facilities require adequate funds to ensure that they can provide services, acquire medicines and supplies, and pay staff. Much of ensuring the availability of funds and creating budgets fall within the responsibilities of facility managers. Therefore, managers should have the skills and competencies as well as the autonomy necessary to allocate and utilize funds.

Key activities

National level

- Set national health sector budgets - this process is often based on historic spending levels and the funds required for inputs such as personnel, medicines, and supplies. National-level health systems stakeholders can strive for a more accurate national health sector by focusing on the outputs and outcomes needed for a health system and working backwards to establish budgets.

- Benefit incidence analysis is a strategy for analyzing how poor areas benefit from government spending relative to wealthier groups and this can help develop evidence-based allocation criteria.22 More information can be found in How to do (or not to do) a benefit incidence analysis

- Ensure that funds get to frontline facilities - There are often challenges with the disbursement of funds in LMIC. These delays can have substantial effects on the motivation of health workers, absenteeism, and ultimately retention in the public sector.

- Streamline budget execution - by evaluating and reducing the number of layers through which disbursements must flow, funds can reach facilities more effectively.

- Make direct payments to facilities - funds can move more efficiently by establishing facility bank accounts and making direct payments to facilities. This requires establishing facility bank accounts if they do not yet exist and ensuring that facility managers have the capacity to manage, track and report on funds.

- Reform (PFM) regulations - PFM regulations promote transparent, effective, accountable management of government finance including preparation of the budget, internal control and audit, procurement, monitoring and reporting arrangement, and external audit.21 By changing PFM regulations, more flexibility and autonomy can be given to facilities to reallocate funds as needed.

Facility level

- Set facility budgets - smaller, government-owned facilities may not have the authority to manage their own finances and may only have control over operational costs or whereas other facilities may have authority to manage all aspects of their budget preparation and use of funds.

- Consult national health sector budget formulation processes - see “set national health sector budgets” above

- Collect relevant data - at the national and facility level, budgets should be based on population size, demographic characteristics such as age and fertility rates, and the burden of disease and associated treatment costs for this population. Getting access to these data is an important step in setting realistic budgets.

- Consider using outputs-based budgeting - outputs-based budgeting (sometimes called , performance budgeting, , and budgeting for results) is when budgets are designed around the resources needed to achieve specific results. This type of budgeting may make health facilities more responsive to achieving stated goals.

- Develop systems for management of funds at the facility level - facilities need systems to track and manage revenues and expenditures so they can compare spending to budget allocations and adjust

- systems should include personnel remuneration, an operation such as medicines, community outreach, and sanitation, and capital spending such as infrastructure improvements

Related elements

- Policy & leadership

- Purchasing & payment systems

- Funding & allocation of resources

- Information & technology

Relevant tools & resources

- WHO, 2022: WHO budgeting for health

- WHO, 2016: Budgeting for Health

- The World Bank, 2014: Results-based financing

- Health Policy & Planning, 2011: How to do (or not to do) a benefit incidence analysis

- RBF Health, 2010: Results-Based Financing for Health (RBF): What’s All the Fuss About?

- Set national health sector budgets - this process is often based on historic spending levels and the funds required for inputs such as personnel, medicines, and supplies. National-level health systems stakeholders can strive for a more accurate national health sector by focusing on the outputs and outcomes needed for a health system and working backwards to establish budgets.

-

A number of different leadership competencies are necessary to result in well-managed facilities. Managers must have individual competencies related to problem-solving and strategic vision, the ability to provide operations management, strong community engagement skills, and human resource management skills.

Key activities

All levels

- Hire managers with competencies relevant to strong management - When hiring managers, ensure that you are assessing the qualities of candidates that contribute to good management and align with the job responsibilities specific to the facility's needs. Some of these include partnership and collaboration, proactive approach, financial planning, strategic decision making, and assessment, planning, and evaluation. It may not be possible to find someone with all of the necessary skills and everyone will need some training, so prioritize hiring someone with the skills that are more difficult to teach and train.

- Use various tools for operations management - operations management is the set of responsibilities in day-to-day facility functions and flow. These tasks may include assigning provider responsibilities, workload and workflow, hours and days of facility operations, infrastructure maintenance and functioning, and availability of drugs and supplies. Process flow mapping can be used to help managers plan for the facility's needs. The following resources may be useful for managers conducting process flow mapping:

- Flowchart template and toolkit – The Institute for Healthcare Improvement has developed a toolkit for gathering the necessary stakeholders and developing a flowchart.

- Mapping curriculum – The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has developed a curriculum for mapping and redesigning workflow to help practices align with a patient-centred medical home model.

- Develop a process for community engagement - Facility managers should ensure that the community provides input into services and is engaged in service delivery. Managers can accomplish this in a variety of ways, including:

- A system for collecting client opinions on their experiences with care when they come to the facility

- Establish a community advisory board, community management committee or add community representatives to existing committees to ensure representation

- Establish a system for taking action based on feedback from patients or other community members

- Provide supportive supervision to staff - supportive supervision is a supervision strategy that relies on collaborative problem-solving and open dialogue. Facility managers should strive to provide supportive supervision to all providers and staff.

Related elements

- Adjustment to population health needs

- Funding & allocation of resources

- PHC workforce

- Information & technology

Relevant tools & resources

- WHO, 2020: Competencies The observable abilities—including knowledge, skills, and behaviours—of individual health workers that relate to specific work activities. Competencies are durable, trainable, and measurable. for nurses in PHC

- National Library of Medicine, 2019: Leadership and management competencies required for Bhutanese primary health care managers in reforming the district health system

- Global Health Action, 2016: An evaluation of the competencies of primary health care clinic nursing managers in two South African provinces

- WHO, 2011: Core competencies in primary care

- Harvard Business Review, 2004: Time-driven activity-based costing

- PATH, 2003: Guidelines for implementing supportive supervision: a step-by-step guide with tools to support immunization

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Understanding and identifying the drivers of health systems performance--referred to here as “related elements”--is an integral part of improvement efforts. We define related elements as the factors in a health system that have the potential to impact, whether positive or negative, the management of services. Explore this section to learn about the different elements in a health system that should be improved or prioritized to maximize the success of actions described in the “take action” section.

While there are many complex factors in a health system that can impact the management of services, some of the major drivers are listed below. To aid in the prioritization process, we group the ‘related elements’ into:

Upstream elements

We define “upstream elements” as the factors in a health system that have the potential to make the biggest impact, whether positive or negative, on policy & leadership.

- Policy & leadership

-

Policies should determine how and which types of funds should be managed at the facility level and establish criteria for effective management and use. Policies also establish national quality standards which are implemented by management at the facility level to cultivate a culture of quality improvement and provide nationally-endorsed measures and targets for performance improvement.

- Adjustment to population health needs

-

Priority setting is a necessary process for appropriately allocating and distributing funds across the health system. In addition, the development of an innovation and learning agenda helps to cultivate a collaborative and improvement-oriented work culture.

- Purchasing & payment systems

-

Systems for strategic purchasing of goods and payment of PHC workforce ensure sufficient funds are available for PHC facilities in decentralized contexts, where relevant.

- Funding & allocation of resources

-

Investments in PHC ensure sufficient funds are available for PHC facilities in decentralized contexts, where relevant.

- Health workforce

-

There must be an adequate supply of appropriately trained, reliable, and available providers to implement and manage effective care models. Additionally, facility managers and leaders must be appropriately trained and capacitated to manage facilities effectively. Finally, systems for registration, licensing, and accreditation of the health workforce can be a key mechanism of quality management infrastructure.

Complementary elements

We define “complementary elements” as the factors in a health system that have the potential to make an impact, whether positive or negative, on service quality. However, we consider these drivers as complementary to, but not essential to performance.

- Information & technology

-

Efficient management practices are often supported by robust information systems for recording, transferring, and analyzing individual provider performance data. Information systems support data collection, transfer, and analysis and can help facility managers and leaders track progress towards targets and changes in performance over time. In addition, robust financial management information systems enable facilities to track and manage funds effectively.

- Population health management

-

Community engagement mechanisms ensure community needs are taken into account in all aspects of service delivery and facility functioning. Additionally, local priority setting can improve the use of funds in line with community needs, although it is not essential for funding allocation to be managed at the facility level.

- Service availability & readiness

-

Provider competence supports care teams to develop clinical competencies and qualities that make them likely to be strong team members. Provider motivation helps to ensure that team members reliably show up to work and fulfill their team responsibilities. Provider motivation mechanisms such as incentives and continuing professional development, among others, can support the successful implementation of performance measurement and improvement efforts. Finally, staff should be involved in and capacitated to understand performance targets and gaps and support data interpretation and quality improvement efforts.

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Countries seeking to improve management of services can pursue a wide array of potential improvement pathways. The short case studies below highlight promising and innovative approaches that countries around the world have taken to improve.

PHCPI-authored cases were developed via an examination of the existing literature. Some also feature key learnings from in-country experts.

- East Asia & the Pacific

- Europe & Central Asia

- Latin America & the Caribbean

-

- Argentina: Agentina's plan Nacer - creating new payment incentives and improving health outcomes

- Chile: Measuring Primary Health Care System Performance Using a Shared Monitoring System in Chile

- Costa Rica: Incentivizing quality and adherence to best practices via performance management

- Costa Rica: Performance Measurement and Monitoring for Continuous Improvement

- Middle East & North Africa

- North America

- South Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

-

- Ethiopia: Improving care through stronger hospital management practices

- Ethiopia: Strengthening hospital management capacity through educational programs

- Ethiopia: Strengthening Primary Health Care Systems to Increase Effective Coverage and Improve Outcomes in Ethiopia

- Rwanda: Enhancing mentoring and supervision to improve the quality of services

- Multiple countries: Integrating communities into facility management decisions through leadership committees

- Multiple countries: The community of practice health delivery: strengthening knowledge sharing to accelerate PHC improvement in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Multiple regions

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Building consensus on what effective management of services looks like and key strategies to fix gaps is an important step in the improvement process. Below, we define some of the core characteristics of effective management of services in greater detail:

-

At a health system level, well-managed systems should have clear pathways for the professionalization of managers by ensuring that there are adequate numbers and appropriate deployment of managers, that they have the necessary competencies to carry out their work, and that there is an environment for them to do their work, meaning that they have clear roles and responsibilities, incentives, and supervision.18 Each of these is discussed in greater detail in this module. It is also important to note that another important component that contributes to good conditions for leadership and management is functional support systems. These include systems for managing money, staff, information, and supplies. Facility funds and expenditures are discussed below, and other aspects of functional support systems are discussed in the modules on information & technology and medicines and supplies.

Distribution of managers

In order to ensure that a health system has an adequate number and effective deployment of health managers, there must be easy access to information about managers as well as the formalization of management posts. Effective information about managers requires a nationally-accessible information system that can be used in the following ways:8

- To provide basic information about vacant and filled management posts

- To inform decisions about employment such as what managers are available, length of service, performance, qualifications and competencies

- To enable research on issues such as retention at the national and sub-national level

- To store information about the qualifications and training records of managers

An information system with these capabilities can then be used to understand needs across a health system and inform future training and deployment as well as allow facilities to make informed hiring decisions. Information systems, including human resources for health information systems (HRHIS), are discussed in greater detail in the information & technology module. Formalized management posts should be available in the HRHIS system and include information about the following:8

- Clarity about the roles and degree of authority of managers at all levels, including what kind of decisions they can make

- Clarity about the competencies required for each level of managers

- Job descriptions that include these details

Competency Competency means to demonstrate a level of ability on a specific task or achieve a level of performance. of managers

As with the hiring of any professional, having a sufficient number of managers available and effectively deployed does not alone translate to better-managed facilities. Managers must have the competencies and training necessary to execute their job responsibilities effectively. A few of the common problems that exist in health manager training include:8

- Trainings are often short, one-time programs or workshops that are not coordinated and are implemented by vertical disease programs or donors with little to no oversight by the Ministry of Health

- Trainings focus on the knowledge of individuals rather than the skills, attitudes, and behaviours of management teams

- Trainings are not integrated into the workplace and often mean that managers must be absent from their jobs and cannot always attend the most relevant training

Very few countries have a national plan for managers to acquire competencies. The development of a national competency framework that identifies the values, attributes, and skills necessary for new managers can help standardize training across the country and help health system stakeholders. For example, Management Sciences for Health has developed a handbook for improving health services that is intended to be used by managers.9 The handbook provides an overview of leading teams through challenges, improving work climate, and reorienting roles in the health system. Handbooks or frameworks such as that can help, in part, health systems identify where there are gaps in training and what kind of competencies are necessary to achieve each objective. Another such framework is the NHS Leadership Qualities Framework which focuses on the following seven domains: 1) demonstrating personal qualities; 2) working with others; 3) managing services; 4) improving services; 5) setting direction; 6) creating the vision; 7) delivering the strategy. Acquiring competencies should take place in a number of different ways to maximize learning. These may include coaching, mentoring, and action learning, with intentional thought towards if the given competency training should be delivered individually or in teams.

Enabling environment

The environment in which managers work also has a significant impact on their ability to be effective. Even managers with all of the necessary competencies may not be able to impart change if they are working within a challenging environment. There are three different considerations and levels of a work environment that correspond to widening layers of influence:8

- Immediate working environment - This includes the way that responsibilities in a health facility are delegated, how teams work together, corruption, the support provided to managers by leadership, incentives and rewards, systems and the ability to prioritize and influence national decisions

- Wider working environment - This includes public and private sector stakeholders such as decentralized authorities, local politicians, private and NGO sector, donors, and the local communities

- Broad cultural, political, and economic context - this includes the standards of governance and the degree to which the rule of law is respected and sets the context for health sector operations

Changes to enable a better environment at each level will necessarily be led by different actors. While changes in the immediate working environment may be mostly at the discretion of facility leaders, the wider working environment and broader context may be influenced by the Ministry of health. Below are a few steps that Ministries of Health can take to ensure positive working environments:8

- Work with donors to harmonize requests and reduce competing or conflicting demands and priorities for managers

- Demonstrate that managers are important and valued and provide incentives for good performance and clear promotion pathways

- Inform managers of new rules, policies, and national plans/guidelines

- Encourage forums, associations and institutes for managers

- Provide supportive supervision to managers (discussed in greater detail below)

- Allow local control - will be more satisfied if they can adapt to local initiatives and have a degree of autonomy

- Acknowledge and discuss constraints in the broader context

-

Identification and implementation of appropriate quality interventions can have a significant impact on specific health services delivery and on the health system at large. Most approaches to national quality strategy development involve one or more of the following processes:

- a quality policy and implementation strategy as part of the formal health sector national plan;

- a quality policy document developed as a stand-alone national document, usually within a multi-stakeholder process, led or supported by the ministry of health;

- a national quality implementation strategy – with a detailed action agenda – which also includes a section on essential policy areas;

- enabling legislation and regulatory statutes to support the policy and strategy.

The predominant functions of governing quality of care at the national and subnational levels encompass leadership and management; the establishment of laws and policies; regulation; monitoring and evaluation; planning; and financing mechanisms.10 A well-considered national quality strategy and operational plan are critical to institutionalizing quality management. It is important that quality management structures are developed with buy-in from stakeholders at every level: fostering a culture that values quality is as important to the success of quality infrastructures as having a plan in place. Quality cannot be expected to be a central aspect of PHC systems if clinical staff are not committed participants – national mandates for quality improvement need supporters and champions. At the same time, that culture alone is not sufficient to guarantee safety, efficiency, and accountability.

Systems for quality improvement should include the following components:1

- A focal person for QI and patient safety at the facility level

- Dedicated resources for action on quality and safety

- Regular application of quality improvement methods (performance measurement and management, quality improvement cycles, audit and feedback, learning systems)

- Processes for clinical audits and mortality reviews (e.g. neonatal and maternal death review and response systems)

- Availability of clinical guidelines/protocols and checklists

- Systems for adverse event reporting including medication harm

- Existence of an up-to-date risk management protocol

- System or mechanism to measure patient experience/ patient voices

Below we discuss different components of quality management and improvement reform, as well as strategies teams, can take to adapt and improve.

Components of quality management and improvement reform

Have an organizational infrastructure in place (national policy document) that can plan, oversee, and shepherd the institutionalization of the quality management infrastructure. This should include people who represent all components of society (planners, practitioners, consumers) touched by PHC quality structures, and a designated leader with clear accountability.11

Ensure quality policy and quality implementation strategy (WHO, Health Finance & Governance Project) are integrated (WHO) as part of the formal health sector national policies, programs, and strategies.3121314

- Develop a quality policy document (WHO) as a stand-alone national document, usually within a multi-stakeholder process, led or supported by the MOH.13

- Develop a national quality implementation strategy, creating intercountry, national, and regional partnerships with a detailed action agenda3121314.

- Elements that should be considered (WHO) in developing a national quality policy and strategy include:13

- National health goals and priorities

- Local definition of quality

- Stakeholder mapping and engagement

- Situational analysis

- Governance and organizational structure

- Improvement methods and interventions

- HMIS and data systems

- Quality indicators and core measures

- Incorporate performance measurement (national policy documents) through the collection, analysis, and reporting of information regarding health system performance.1115

Prioritize interventions likely to have a high impact on quality (WHO), including reducing harm to patients, improving clinical effectiveness, creating an enabling systems environment, and engaging patients, families, and communities.16

- Interventions around reducing harm include inspections of institutions for minimum safety standards, safety protocols and checklists, and adverse event reporting;

- Interventions around improving clinical effectiveness include clinical decision support tools, clinical standards, pathways, and protocols, morbidity and mortality reviews, and collaborative and team-based improvement cycles;

- Interventions around enabling systems environment include registration and licensing, external accreditation, clinical governance, and public reporting;

- Interventions around engaging patients, families, and communities include formalizing community engagement and empowerment mechanisms, health literacy, shared decision-making, peer support and expert patient groups, patient experience of care, and patient self-management tools.1617

Focus on strengthening areas (WHO) that are characteristic of a well-established quality program, including information collection and sharing, a formal policy process in which partners at every level contribute to its development and long-term sustainability, and an executive function with autonomy within or outside government.3

Develop a clear conceptual framework and vision and a supportive environment

To begin, it is critical for implementers to develop a robust conceptual framework within which performance indicators can be developed. This can be done at both the national and sub-national and/or facility level. While myriad frameworks exist, it will be important to develop a framework that will provide a comprehensive and meaningful assessment of the primary health care system, such as the newly launched WHO Operational Framework for Primary Health Care. Further, alignment with broader goals defined in the National Strategic Plan can support cross-cutting goals for health system performance, such as Universal Health Coverage and responsiveness to population health needs. A common conceptual framework will also promote the generation of meaningful, comparable information on health system performance, including variation in performance outcomes.1819 Implementers can read more about developing a framework for performance measurement and management in the WHO’s Framework for Health System Performance Assessment.

Because the fundamental role of performance measurement and management systems is to hold stakeholders accountable to priority goals and objectives, it will be important to ensure that mechanisms and systems for social accountability and quality improvement are in place and well-functioning across the health system.18 Learn more in the Improvement Strategies for a multi-sectoral approach.

To create an enabling environment for such systems, it will be important for leaders across the health system to establish routine, collaborative processes for selecting performance indicators and a culture of learning and improvement. It is important to involve staff and other stakeholders, such as community leaders, patients, and families in this process to ensure that the chosen metrics are recognized and accepted by all staff across the facility and relevant to identified population health needs.

Select performance indicators

Once framework(s) have been established, implementers should then define and choose performance indicators that fit into the selected framework(s) and satisfy a number of criteria, such as validity, acceptability, and reproducibility. In addition, it is important to consider how the performance indicators to be monitored and communicated will fit into the broader political and organizational context.1819 Often, the metrics that teams select will feed into or be guided by existing national- or facility-level goals and priorities, so as to enable leaders and staff to track progress toward these objectives. See Table 2 of the WHO’s document on Performance measurement for health system improvement for common health performance measures and examples of indicators that enable health systems to capture progress toward these areas.

The Safety Safety refers to the practice of following procedures and guidelines in the delivery of PHC services in order to avoid harm to the people for whom care is intended. Net Medical Home Initiative implementation guide identifies four considerations when selecting targets for performance management:

- Align with nationally-endorsed measures and standardized data definitions when possible – these data may already be collected and could therefore reduce staff time and information system changes

- Consider the resources needed to be able to collect and report a measure compared to the value that the measure serves – some data may be particularly laborious or time intensive to record and collect. If so, their utility should be carefully considered.

- Ensure a comprehensive measure set to reflect changes – measures should be mapped to the processes and outcomes that are expected to take place during service delivery changes

- Consider audience – various stakeholders in a health system will be interested in different measures. Leaders should consider the range of stakeholders to whom data will be presented when identifying performance targets and measures.20

In addition to the considerations above, the type/framing of metrics may also be important for successful measurement implementation. Clear framing, for example by using the SMART method, will support implementers to identify reasonable and realistic metrics for the context and ensure that the chosen metrics are understood and accepted by relevant stakeholders.

Institute supportive systems and infrastructure

After key indicators and associated targets are selected, the second component of performance measurement and management is instituting a measurement/monitoring system to track progress towards targets. Different groups of stakeholders will have different information needs in terms of the type of information required for performance measurement and management, its detail and timeliness, and the level of aggregation required. It will be important to design performance management systems to serve these diverse needs, including through the use of well-designed, comprehensive information and communication infrastructure. For example, government-level stakeholders may be interested in data that provides insight into equity in access to care across the health system whereas facility-level stakeholders may focus more on data related to provider competence and other facility-level outcomes.18 For more information on strengthening health information systems for performance measurement and monitoring, stakeholders can reference The WHO’s SCORE for Health Data Technical Package Tools.

To act on the information generated by such systems, managers must have access to performance measurement data, have the capacity to interpret data, and be able to set action plans based on gaps identified in the data. Staff should be involved throughout the process; they should be aware of targets, receive updates on performance data, and be engaged in data interpretation and development of action plans. Learn more about building leadership and staff capacity for use of such systems in the information and technology module as well as in facility management capability, below.

Another important consideration when assessing measurement and monitoring systems is the frequency with which data are collected, analyzed, and shared. Facility managers must consider how long it will take to collect a sufficient quantity of data to make meaningful conclusions and balance that with any reporting requirements or internal improvement processes.

When implementing performance measurement systems, stakeholders should be aware of how individual provider performance is measured and communicated. Data on provider performance can complement facility-level performance data; with both, stakeholders can understand how individual providers contribute to successes or areas for growth within a facility. However, provider performance management should be designed such that feedback is actionable and encourages improvement – sometimes with incentives – rather than purely punitive. If providers feel that performance measurement is futile and/or only used to punish them, they will not be motivated to improve and actively collaborate with managers to identify areas for growth. More information is included in the service availability and readiness module.

Systems for individual-level provider performance management should incorporate provider perceptions and involve collaboration between providers and managers to develop actionable improvement plans. Some examples of questions that managers may ask providers to catalyze performance review and improvement include:

- Please describe results or responsibilities you delivered that contributed to better results for your team and/or organization.

- Please describe the results or responsibilities you fell short of achieving. What could have been done to achieve better results?

- What part of the organization’s mission do you demonstrate well?

- What part of the organization’s mission do you struggle to demonstrate?

- How do you want to grow in this team, and what steps are required to get there?

Adapting and improving

Data from performance measurement systems should be shared with staff and other relevant stakeholders and incorporated into future facility goals/targets and improvement plans. Analyses of data from facilities may suggest that facility leaders should adapt targets, set new ones, develop an intervention, or explore various processes further.

Many of the principles of performance measurement and management are captured in a variety of quality improvement methodologies and tools. In general, these methods suggest using data to identify a problem and then identifying the factors that led to the problem. This process can help surface potential solutions. Some useful resources include:

- Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) – PDSA is a framework for a cyclical improvement process where implementers plan an initiative, implement the plan, study the results, and make further improvements.

- Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) – SBAR is a communication method for team members to identify and discuss patient conditions.

- The Fishbone Method – The fishbone method can help teams understand the factors that are driving system failures.

- 5 Whys – The 5 Whys is another root cause analysis method. As the name suggests, in this method a provider or team considers a problem and asks and identifies why it is occurring five times.

- Standards-Based Management and Recognition (SBM-R) methodology – SBM-R is a performance and quality improvement approach that includes 1) setting standards 2) implementing standards 3) measuring progress, and 4) recognizing the achievement of those standards

- IHI Open School – The Institute for Healthcare Improvement Open School has a number of different resources for quality improvement.

-

The availability of funds and how funds reach facilities and are integrated into s can shape the supply, accessibility, and quality of services, resulting in flexibility or constraints for primary care providers. Facility managers’ ability to budget, manage and track funds at the facility level can impact health care providers' ability to be responsive to changing disease burdens and patient needs.

How are facility budgets set?

Facility budgets provide an outline for how a given amount of money received from a particular source is intended to be spent. Ideally, budgets should be a tool to proactively plan for future activities and track the use of funds in real-time. Budget A document that outlines forecasted revenue and planned expenditure for an entity (government, subnational unit, or health facility) over a defined period of time. Budgets indicate how funds are meant to be allocated to achieve certain objectives. preparation exercises help facilities estimate how much funding they will have available and how they will use that funding. In larger PHC facilities with authority to manage their own finances, budget preparation is an essential component of planning (such as what kinds and how many medicines and supplies to buy, which staff to hire, and how to meet the evolving needs of the patients and communities the facility serves). Many smaller government-owned PHC facilities may not have this authority – staff allocations may be decided at a higher level and medicines provided in-kind – and their budgets may cover only on facility operational costs or use of .

Improving how budgets are set

Health sector budget allocations should be set utilizing need-based, empirical evidence, including population size, demographic characteristics like age and fertility rates, and the burden of disease and associated treatment costs. Countries can improve the budgeting process in some of the following ways:

- Moving to a combination of (where the central budgeting authority determines resource allocations based on revenues available) and (where facilities estimate the budget needed to meet local service delivery needs).

- Creating easy-to-understand allocation formulas with a system of financial transfers for poorer areas.21

- Using benefit incidence analysis to understand how much poor areas benefit from government spending, relative to wealthier groups, and can assist in developing evidence-based allocation criteria.22 (For further reading on benefit incidence analysis and when it can be utilized, see How to do (or not to do) a benefit incidence analysis.)

- Using output-based budgeting (also known as “performance budgeting”, “”, “” and “budgeting for results”)14 to improve the responsiveness of budgets to changing local health needs.

- Orient output- or program-based budgets around achieving specific results and the anticipated resources needed to achieve those results. This type of budget orientation can help hold facilities accountable for delivering outputs (such as successful prevention, diagnosis and treatment of patient conditions), rather than simply spending inputs23 and help show elected officials “what will be accomplished with the money, as opposed to merely showing that it has been used for the purchase of approved input”.14

For further information on budgets and how they can impact performance, see Budgeting for Health.

Getting funds to frontline facilities

To support high-quality primary health care delivery, funds need to reach frontline facilities in a timely and predictable fashion, and in full. But in many LMICs, challenges with getting public funds to lower-level facilities are common. While salaries for government employees are often paid directly from a central-level ministry, operational and capital funds often have challenges associated with disbursement.

Common challenges to getting funds to facilities include leakage in funds transfers along the chain from central, regional, and local levels of government to facilities; and delays in disbursement24. Public expenditure tracking surveys (PETS), which carefully triangulate what proportion of disbursed public funds are received by lower-level facilities, often reveal delays and leakages that prevent facilities from receiving operational funds. In Chad, for example, only 18% of the non-wage recurrent budget reached the regional level, and front-line providers received less than 1% of funds21. In Ghana, a survey found that only 20% of non-salary funds reached health facilities, and in Tanzania, the estimated leakage rate – meaning funds either disappeared or were not used as budgeted – of non-salary funds was 41%24. (For a brief overview of PETS and how to conduct one, see: Economic and Social Tools for Poverty and Social Impact Analysis: PETS.)

Delays in budgets can present challenges for health systems. Budget A document that outlines forecasted revenue and planned expenditure for an entity (government, subnational unit, or health facility) over a defined period of time. Budgets indicate how funds are meant to be allocated to achieve certain objectives. transfer systems that require multiple steps in the payment process between the Ministry of Finance and facilities can create delays in funds reaching facilities, whether due to complex administrative procedures or leakage as funds move through the system. Such delays can translate into low budget execution rates (the proportion of budgeted funds which are spent by the end of the fiscal year) for the health sector. In Nepal, for example, approximately 20% of the overall 2012 health budget was disbursed in the final quarter of the year, resulting in District Health Officers spending only 80% of budgeted funds22. Low budget execution rates, in turn, can jeopardize future allocations from the Ministry of Finance, which might blame the underspend on inefficient facility management rather than on late disbursements.

Delayed or irregular payments also have a negative impact on health workers and can lead to demotivation, mistrust, and absenteeism. If health workers do not receive their salaries, they may charge informal payments to patients or refer patients in public facilities to their own private clinics in an effort to make up for lost wages.24 Over the long term, staff remuneration challenges can make health workers less interested in taking a government-funded health care position in the first place, contributing to staffing shortages in the public sector.

There are a number of strategies that can be used to address the challenges discussed above. Successful budget execution entails coordinating and streamlining the processes that lead to effective funds transfers from the national treasury to the Ministry of Health and then to districts and health providers. Simplifying funds allocation systems by reducing the number of layers through which disbursements must flow can increase the timeliness of payments and reduce leakages. Establishing facility bank accounts and making direct payments to facilities can more efficiently move funds to front-line providers (see further discussion below). This will require increasing facilities’ capacities to manage, track, and report on funds provided.

Addressing central-level cash management problems may also be necessary. Countries that use cash budgeting processes (meaning cash must be available before the budget is disbursed) often experience unpredictable funds availability. If the central budget is unrealistic due to limited cash at hand, Ministries of Finance often engage in cash rationing. Disbursement of funds and staff remuneration can be delayed for many months due to liquidity problems and then is often disbursed in larger sums towards the end of the fiscal year24. Improvements in timely, regular health worker payments are likely to require budget process strengthening and improvement in budget execution at the central level.

Management of funds at facilities

Facility financial management refers to systems and processes at the health facility level to track and manage revenues (funds received from government transfers, insurance payments, and patient fees) and expenditures (outlays on personnel and other inputs). Strong financial management systems allow facilities and the health system overall to manage and track funds effectively, comparing spending to estimated budget allocations and adjusting as needed. They also help identify when underperformance is due to inefficiency or insufficient funding and plan for future spending needs.

Common components that health facilities need to manage include personnel remuneration, operations, and capital spending.

- Personnel remuneration includes staff salaries and fringe benefits. Staff who are government employees may be hired and paid directly by the central or subnational government. Sometimes the civil service is entirely administered by another ministry outside the health sector – for example, a Ministry of Finance – and their costs will not be handled by the facility at all. In some contexts, health facility managers can hire additional contract staff to cover for staff shortages or fill specific positions (e.g. laboratory services). These costs would be managed directly by the facility.

- Operations include the non-personnel inputs required to run the facility and can include:

- Medicines, supplies and equipment. These are either procured centrally and distributed in-kind, or facilities may receive funds directly and manage their own procurement.

- Community outreach activities. These would include allocations for vehicles and fuel costs, educational supplies, etc.

- Maintenance, utilities, and sanitation.

- Capital spending includes infrastructure improvements. These may also be managed centrally, sometimes by a separate public works ministry.

Many primary care facilities have only limited authority and autonomy to manage their own funds. They may not have a facility bank account that they can access directly; their staff may be managed and paid centrally and they may have little ability to hire and fire staff locally. Medicines and supplies may be provided in kind, and facility managers may not have the ability to procure them directly or adjust quantities based on patient needs. If they do have direct access to funds, there may be strict regulations about the use of those funds and little flexibility in their allocation. Clinical staff might lack training in financial management, and the information infrastructure necessary for good accounting may be limited.

In addition to public funds, internally generated funds – including user fees and other revenues collected directly by facilities – may constitute a pool of discretionary funds at the facility. In some contexts, internally generated funds are controlled by facilities, while in others, facilities are required to return them to the district or central treasury. If controlled by facilities, these funds are sometimes “off-budget” (not included in the official budget) and have weaker reporting requirements21. In many contexts, different sources of funding are intended for different portions of the facility budget, but facilities often have difficulties managing and accounting for these fragmented funds. These multiple funding flows and multiple payment methods create an incoherent set of incentives for health workers and can result in undesirable provider behaviour, such as patient cream skimming and cost-shifting.

“Provider autonomy” refers to the extent to which frontline facility managers have the authority to function as funds managers and to change the mix of inputs and services they provide based on their patients’ needs (e.g. to respond to an unexpected outbreak of disease or to adapt to a change in drug pricing). When health facilities have strong financial management capacity and authority to make some financial management decisions, they are more likely to adjust service provision and deploy inputs based on the needs of the population22.

Introducing greater provider autonomy in funds management at the facility level typically requires reforms to a country’s (PFM) regulations25. PFM regulations aim to promote transparent, effective, accountable management of government finances21. They touch upon all phases of the budget cycle, including the preparation of the budget, internal control and audit, procurement, monitoring and reporting arrangements, and external audit. However, some PFM rules – intended to ensure predictability of spending and careful fiscal control -- can create inefficiencies in the health sector, where health care needs are unpredictable and quick responses to crises are essential.

Changes to PFM regulations may be needed to increase the authority of lower-level spending units (including health facilities) to flexibly move funds across budget lines. This can improve PHC performance by enabling facilities to respond to changes in population needs and provide payment incentives more nimbly21. (In general, these changes should be integrated into broader health system reforms26, including but not limited to primary care, and must be closely coordinated by the Ministry of Finance.)

Budget A document that outlines forecasted revenue and planned expenditure for an entity (government, subnational unit, or health facility) over a defined period of time. Budgets indicate how funds are meant to be allocated to achieve certain objectives. officials may consider disbursing some cash income directly to primary care facilities, rather than only in-kind inputs. This can provide facility managers more flexibility to reallocate funds as needed. Recognizing that most medicines and supplies will be bulk-procured centrally, allowing facilities to procure small amounts of medicines and supplies with their funds may reduce both wastage and stock-outs and improve responsiveness to short-term local needs. Dedicated facility bank accounts are necessary for facilities to receive direct funds transfers, and allowing them to receive cash income and open bank accounts may require changing their legal status; this can be a serious bottleneck in some contexts. Facility bank accounts can also help expedite disbursements and increase budget execution rates.