|

|

|

Strong information systems and technologies are comprehensive, interoperable, and interconnected.

They are also user-centred and backed by a robust policy environment, including a national strategy for eHealth.

Information & technology refers to the systems and innovations used for collecting, processing, storing, and transferring data and information that are used for planning, managing, delivering, and improving high-quality health services, including effective Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. systems. This area focuses on the availability, Coordination Coordinated care includes organizing the different elements of patient care throughout the course of treatment and across various sites of care to ensure appropriate follow-up treatment, minimize the risk of error, and prevent complications. Coordination of care happens across levels of care as well as across time, and often requires proactive outreach on the part of health care teams as well as informational continuity. , and Interoperability Interoperability is the ability of different information systems, processes, devices, or applications to connect in a coordinated manner, within and across organizational or geographic boundaries to access, exchange and cooperatively use data amongst stakeholders to respond to disease instances, with the goal of optimizing the health of individuals and populations. of these systems and the requisite infrastructure and policies needed for their operation, including digital technologies that support innovation, communication, and Telemedicine “The delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by use all health care professionals using information and communications technologies for the exchange of valid information for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and the continuing education of health care workers, with the aim of advancing the health of individuals and communities.” .

Well-functioning information & technology include:

- Information systems are the systems used for collecting, processing, storing, and transferring data and information used for planning, managing, and delivering high-quality health services. 123

- Digital technologies for health, or digital health, is a broad term to describe Electronic health or eHealth “eHealth involves a broad group of activities that use electronic means to deliver health-related information, resources and services: it is the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) for health.” (the use of information and communication technologies for health), mobile or m-health (including telemedicine and remote patient monitoring), and other digital technologies for health (including medical and assistive devices).

- Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. is the ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. 456

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Every country should improve information & technology. Before taking action, countries should first determine where to target improvement efforts. Read on to learn how to use country data to:

- Make informed decisions about where to spend time and resources

- Track progress and communicate these updates to constituents or funders

- Gain new insights into long-standing trends or surprising gaps

Countries can measure their performance using the Vital Signs Profile (VSP). The VSP is a first-of-its-kind tool that helps stakeholders quickly diagnose the main strengths and weaknesses of primary health care in their country in a rigorous, standardized way. The second-generation VSP measures the essential elements of PHC across three main pillars: Capacity, Performance, and Impact. Information & technology is measured in the Inputs domain of the VSP (Capacity Pillar).

If a country does not have a VSP, it can begin to focus improvement efforts using the subsections below, which address:

- Key indications

-

If your country does not have a VSP, the indications below may help you to start to identify whether information & technology is a relevant area for improvement:

- Poor data management: Information systems produce untimely, unreliable, and/or incomplete data. Systems to ensure data quality and security are not in place or are poorly enforced.

- Ineffective information systems use: Planners, providers, and/or patients have difficulty accessing or using data to support effective decision-making and service delivery.

- Poor user capacity: Information systems are not user-friendly and/or are poorly integrated into existing workflows.

- Fragmented platforms: No reliable platform is in place to integrate and manage the different types of information systems.

- Lack of data on PHC performance: Existing information systems collect little to no data on PHC- specific indicators and PHC performance.

- Poor technical capacity: Information systems are limited in scope and lack the capacity to triangulate, exchange, or use comprehensive information across sectors and health care settings.

- The following functions of effective surveillance are poorly functioning or not in place in your country’s surveillance system:

- Track health and burden of disease metrics (morbidity, mortality, incidence);

- Detect, report, and investigate notifiable disease, events, symptoms, and suspected outbreaks or extraordinary occurrences;

- Continuously collect, collate, and analyze the resulting data;

- Submit timely and complete reports from local to higher levels of the system and from higher levels of the system back to lower/community levels.

- Key outcomes and impact

-

Countries that strengthen information & technology may achieve the following benefits or outcomes:

- At the policy level, where the information generated from well-functioning information systems supports the capacity of the health system to sense and adapt to emerging and existing population health needs, create effective health policies, monitor health equity, and build health system resilience. 3

- At the facility and subnational management levels, where routine use of data management information systems to establish targets, monitor progress, and implement ongoing improvement initiatives supports effective facility organization and management, including the availability, control, and appropriate management of drugs and supplies, facility infrastructure, workforce, and funds.

- At the service delivery level, where information systems such as personal care records and civil registration and vital statistics systems collect critical information on local population health that supports evidence-informed decision-making and the provision of high-quality PHC services. 7 In particular, well-functioning information systems empower and engage patients, improve communication among team members, and improve continuity and coordination of care. 8910

- Across levels, surveillance enables a country to collect comprehensive information on population health to inform the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health, and strengthen the country’s ability to respond to emerging health needs and build resilience.

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Explore this page for a curated list of actions to improve information & technology, which embark on:

- An explanation of why the action is important for information & technology

- Descriptions of activities or interventions countries can implement to improve information & technology

- Descriptions of the key drivers in the health system that should be improved to maximise the success or impact of actions

- Relevant tools and resources

Key actions:

-

Effective health information systems are comprehensive, capturing data about health services at all levels of the health system. Well-functioning health information systems yield high-quality and comprehensive data and information essential for enabling effective surveillance and priority setting, population health management, facility management, and the achievement of the core functions of PHC, including coordination, continuity, comprehensiveness, and person-centeredness.

Key activities

National and health system level

- Prioritize comprehensive health information systems. Comprehensive information systems report and use a broad spectrum of health-related data from both the public and private sectors, and other relevant non-health sectors. Comprehensive information systems integrate data from the following types of systems across different levels of the health system and different types of facilities:

- health management information systems,

- information systems,

- patient medical records,

- financial management information systems,

- logistics management information systems,

- civil registration and vital statistics,

- national human resource information systems, and

- a regular system of facility, patient, and community surveys.

- Further, comprehensive health information systems include a national patient registry, beyond empanelment and civil registration and vital statistics. National patient registries can be used to collect and track data on infectious, chronic, and genetic diseases. They are useful to track burden and trends in diseases, provide data for resource allocation planning and priority setting, provide a tool for dissemination of treatment products, and improve global data on specific illnesses and disorders. 1112

- Prioritize and in the health information system. Information systems are considered interoperable when the same information is captured in the same or similar format and channels are established such that information can be exchanged, triangulated across data sources, and used across multiple sectors. Considerations for assessing the interoperability and interconnectedness of information systems in your country include:

- Is there a platform in place to integrate and manage the different types of information systems in your country? (i.e. DHIS2) Is this cost-effective, secure, and easy to use? Is this platform fully digitized?

- Are there data quality standards in place that are appropriately regulated and enforced to ensure standardized quality and use?

- Does information follow patients as they move geographically or between different levels of the system?

- Does your country track the proportion of primary health care facilities with all of the identified standard safety precautions and equipment in place?

- Ensure information systems capture essential PHC indicators and enable tracking of PHC capacity and performance. In order for information systems to support strong PHC service delivery, it is critical that they be designed to capture and report on PHC-specific indicators and PHC performance. Considerations for determining whether your system does this effectively include:

- Do your country’s information systems capture key PHC indicators, such as those included in the PHC Vital Signs Profile?

- Do your country’s information systems allow users to track PHC capacity and performance specifically? For example, can you track the availability of key inputs such as facility infrastructure, drugs and supplies, funds, and workforce at PHC facilities compared to hospitals? Can you specifically track and assess the competencies of the PHC workforce and PHC service quality compared to competence and quality in secondary or tertiary care levels?

Related elements

- Purchasing & payment systems

- Funding & allocation of resources

- Physical infrastructure

- PHC workforce

- Service quality

Relevant tools & resources

- Prioritize comprehensive health information systems. Comprehensive information systems report and use a broad spectrum of health-related data from both the public and private sectors, and other relevant non-health sectors. Comprehensive information systems integrate data from the following types of systems across different levels of the health system and different types of facilities:

-

In order for information systems to be useful and used, they must be designed to ensure that they are user-friendly and intuitive for all types of health workers and decision-makers and that they can be easily and efficiently incorporated into workflows. Additionally, the intended users of information systems need appropriate and ongoing training in how to effectively and efficiently use information systems.

Key activities

National and health system levels

- Prioritize compatibility with the needs and skills of users across all levels of the health system in the design and functionality of information systems. This will facilitate the effective use of these tools and broader buy-in from users.

- Consider the following when assessing health system performance:

- Whether information systems have a user-friendly structure and fit efficiently and intuitively into existing workflows with clearly-defined standards (i.e. standard operating procedures for data collection, analysis, and use) and principles to ensure standardization of data quality and use.

- Whether information communication technologies are suitable to the local context. If not, are systems in place to train and capacitate health workers to appropriately and effectively use new technologies to perform their duties associated with the collection of health data, data analysis, and data use?

- Whether the information produced by the different types of information systems in your country is complete, accurate, and accessible to relevant users at the right place at the right time. Is it in a format that users can easily review and use to support quality, , and of care (i.e. identify and follow trends, address gaps in care, etc.)?

Related elements

-

A strategy for e-health facilitates a country’s ability to plan and achieve its e-health goals. “While electronic information can have a positive impact on health service delivery, it can also fail to support and promote population health if the information is fragmented and is not appropriately managed… The use of digital health data should be strategic, support national health goals and be closely linked to the national M&E and HIS plans.” 13

Key activities

National & health system levels

- Develop or strengthen a national e-health/digital health strategy that includes the following components, 13 and is mindful of these widely-endorsed health data governance principles. 14

- Discusses health

- Describes health data standards and exchange

- Includes a strategy/policy on telehealth/

- Includes a plan to handle data security issues

- Specifies and data storage

- Specifies access to data

- Specifies alignment and integration with national health information system strategy

- Specifies financing

- Specifies organizational roles and responsibilities

- Adopt or strengthen digital technologies for health:

- Prioritize transitioning to an electronic-based information system: While much can be accomplished with paper-based systems, the most effective information systems are fully digitized and interoperable across all levels of care. To get started on the transition from paper-based to fully electronic in your country, you might consider:

- What elements of information systems in your country are electronic vs. paper-based?

- Is there variation in the format used, for example by geographic region, level of care, type of facility, or type of information system?

- Are there policies and plans in place to support investments in infrastructure that supports electronic information system use, for example, skills training, modernized technologies, and necessary facility infrastructure?

- Prioritize transitioning to an electronic-based information system: While much can be accomplished with paper-based systems, the most effective information systems are fully digitized and interoperable across all levels of care. To get started on the transition from paper-based to fully electronic in your country, you might consider:

- Implement or increase enhanced records (EHR) and health management information system capacities and use. This could include functions such as picture archiving, communication systems, and automatic vaccination and medication alerts.

- Ensure or expand access to among patients and providers. PHC is an increasingly common use of telemedicine. 15 Targets for its expanded access and use include increased use for delivery of PHC, mental health services, and community health education and awareness programs. 16

Related elements

Relevant tools & resources

- WHO, 2022: Webpage on Digital Health

- TDR, 2022: Webpage on Digital Health Technology

- WHO, 2021: Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020-2025

- WHO, 2021: WHO compendium of innovative health technologies for low-resource settings 2021. COVID-19 and other health priorities

- WHO, 2012: National eHealth Strategy Toolkit

- Health Data Governance Principles

- Develop or strengthen a national e-health/digital health strategy that includes the following components, 13 and is mindful of these widely-endorsed health data governance principles. 14

-

Effective priority setting helps governments make the best use of limited human and financial resources and take advantage of new methods and techniques to strengthen surveillance. 17

Key activities

National and health system levels

- Align with national and subnational priority setting processes to review disease control priorities and identify which health conditions and diseases should be closely monitored and how. These priorities should reflect population health needs and will subsequently inform how resources for surveillance should be utilized. When considering what priority diseases to select, questions stakeholders might consider include: 18

- Does the disease have a significant impact on morbidity, mortality, and disability? (morbidity, disability, mortality)

- Does it have significant epidemic potential (e.g. cholera, meningitis, measles)

- Is the disease named as a target of a national, regional, or international control plan? (e.g. the International Health Regulations)

- If the data were collected, would they lead to significant public health action? (e.g. immunization campaigns or other specific control measures provided by the national health system)

Related elements

Relevant tools & resources

- WHO, 1999: Recommended Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. Standards

- WHO, 2006: Setting Priorities in Communicable Disease Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health.

- World Bank: Disease Control Priority Series

- Align with national and subnational priority setting processes to review disease control priorities and identify which health conditions and diseases should be closely monitored and how. These priorities should reflect population health needs and will subsequently inform how resources for surveillance should be utilized. When considering what priority diseases to select, questions stakeholders might consider include: 18

-

To ensure the rapid response and systematic monitoring of a comprehensive spectrum of health threats and diseases, countries’ surveillance strategies may differ between local, regional, and national levels. Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. systems that engage multiple strategies will require coordination among the different health authorities at multiple levels of the health system. 19

Key activities

National and health system levels

- After priority diseases have been selected, develop a plan of action. 18 Countries should regularly assess their national surveillance system and develop and implement national action plans to improve the core functions of surveillance. 20

- Ensure the following surveillance elements are included in the national plan:

- Plans for developing or enhancing event-based and syndromic surveillance. Users can look to WHO guidance on implementation in national legislation for additional support in facilitating surveillance and response activities that meet International Health Regulation (IHR) obligations. 21 Policy and legislation should also promote investment in infrastructure that support the functions of event-based and syndromic surveillance systems, such as electronic information systems and modernized laboratories and clinics.

- Public health emergency response plan. Procedures, plans, and/or strategies should be in place to activate responses to public health emergencies at the local level and elevate them to higher levels as needed. Users can find more information in the Emergency “An extraordinary situation in which people are unable to meet their basic survival needs, or there are serious and immediate threats to human life and well-being. Emergency interventions are required to save and preserve human lives and/or the environment. An emergency situation may arise as a result of a disaster, a cumulative process of neglect or environmental degradation, or when a disaster threatens and emergency measures have to be taken to prevent or at least limit the effects of the eventual impact. (UNDP)” Response Operations Indicator of the WHO’s Joint External Evaluation Tool: International Health Regulations (2005).

- System for sending and receiving medical countermeasures and health personnel during a public health emergency. Medical countermeasures are products that can be used in a public health emergency including biological products, drugs, and devices. Users can find more information in the Medical Countermeasures and Personnel Deployment Indicator of the WHO’s Joint External Evaluation Tool: International Health Regulations (2005).

- Regularly evaluate and test national surveillance procedures, plans, and/or strategies, either through simulations or real health threats, to ensure continuous operational capacity. 20

- Establish and implement guidelines on standard operating procedures (SOPs) for surveillance response at national and subnational levels as an important surveillance early-warning function.

- Ensure regular evaluation of event management. This can involve technical guidelines or standard operating procedures for event management. Ideally, event verification, risk assessment, investigation, and analysis take place regularly and systematically. These should guide national and subnational responses, and findings should be disseminated through epidemiological reports to all relevant sectors.

Related elements

- Physical infrastructure

- Policy & leadership

- Resilient facilities & services

- Service availability & readiness

Relevant tools & resources

- WHO, 2022: Compendium of resources on strengthening national emergency response

- GHS Index: 2021 Global Health Security Index

- WHO, 2016: Joint external evaluation tool: International Health Regulations (2005)

- WHO, 2009: International Health Regulations (2005): Toolkit for implementation in national legislation

- SORMAS ( Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. Outbreak Response Management and Analysis System

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Understanding and identifying the drivers of health systems performance--referred to here as “related elements”--is an integral part of improvement efforts. We define related elements as the factors in a health system that have the potential to impact, whether positive or negative, information & technology. Explore this section to learn about the different elements in a health system that should be improved or prioritized to maximize the success of actions described in the “take action” section.

While there are many complex factors in a health system that can impact information & technology, some of the major drivers are listed below. To aid in the prioritization process, we group the ‘related elements’ into:

Upstream elements

We define “upstream elements” as the factors in a health system that have the potential to make the biggest impact, whether positive or negative, on information & technology.

- Policy & leadership

-

Developing and strengthening surveillance response at all levels of the health system relies on the long-term financial and political commitment of human, financial, and material tools and resources and the establishment of a strategic plan of action to monitor and respond to the most important population health needs. Investment in surveillance should begin with a systematic review of national priorities for surveillance, including the prioritization of diseases and health events for public health surveillance, to ensure the broader surveillance system is high-functioning and reflects national disease control priorities. Legislation and national policies should determine the establishment and operation of surveillance systems; alignment with globally recommended surveillance standards; PHC policies on public health emergency plans; and resource mobilization. They should also be supportive of digital technologies and information infrastructure that reinforces comprehensive, interoperable information systems.

- Physical infrastructure

-

Health workers must be supported by appropriate facility infrastructure and systems for effective population health management, such as empanelment and local priority setting, in order to effectively and proactively detect, monitor, and respond to health threats and continuously monitor communities’ needs over time. 222324 Laboratories and clinics are typically the main platform for event-based and syndromic surveillance systems. Facilities should be equipped or in networks with laboratories with biosurveillance and laboratory-based diagnostic capacities (such as HIV genotyping) and clinics with point-of-care diagnostic capacities. For the timely and effective detection of public health threats, these laboratories must conform to international quality standards and adhere to standard operating procedures for transporting and collecting specimens that require advanced diagnostics at the national level.

- Organisation of services

-

Laboratories and clinics are typically the main platforms for event-based and syndromic surveillance systems. The functional capacity of these laboratories and clinics is determined by the organization of services.

Complementary elements

We define “complementary elements” as the factors in a health system that have the potential to make an impact, whether positive or negative, on information & technology. However, we consider these drivers as complementary to, but not essential to performance.

- Adjustment to population health needs

-

The coordinated collection and use of high-quality data at all levels of the health system rely on the presence and functionality of information systems with a built-in capacity for rapid detection and response, such as real-time alerts and predictive modelling. To be of optimal use, information systems must produce reliable, complete, and timely information that ensures interoperability from a wide range of data sources and interconnectedness across all levels of the health system. 822 Participatory priority setting supports the identification of surveillance priorities to be monitored for managing both the delivery of health services and the status of population health.

- Purchasing & payment systems

-

Purchasing and payment systems often impact the acquisition of and investment into necessary information & technology, making it an important factor for consideration.

- Funding & allocation of resources

-

Changes to spending on PHC as a whole can impact the financing available to PHC information systems and technological investments, however, spending on PHC alone would not necessarily impact this input.

- Health workforce

-

Surveillance relies on the availability of a fully competent, coordinated, and multidisciplinary health workforce responsible for public health surveillance and response at all levels of the health system. 22232526 A detailed national workforce strategy that is tracked and reported on annually is a necessary prerequisite for training and sustaining a competent workforce. A national workforce strategy should delineate plans to provide continuous education and retain and promote a qualified workforce within the national health system. 27

- Population health management

-

Local priority setting enables the identification of the local burden of disease and population health needs that will merit surveillance; it is also an important platform for data collection. Additionally, community engagement helps to ensure that information and communication technologies are suitable to the local context.

- Management of services

-

Given some facility funding is decentralized, it can be complementary to the maintenance of and building of information systems. Additionally, management of services allows for better, more strategic and efficient use of funds at the facility level. Finally, quality management infrastructure at the facility level helps to ensure data quality standards are in place, regulated, and enforced.

- Service availability & readiness

-

Because many stakeholders are involved in surveillance, it is important to facilitate trust among different levels of the health system to improve communication and accuracy of information gathered. Additionally, surveillance relies on the availability of a fully competent, coordinated, and multidisciplinary health workforce responsible for public health surveillance and response at all levels of the health system.

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Countries seeking to improve information & technology can pursue a wide array of potential improvement pathways. The short case studies below highlight promising and innovative approaches that countries around the world have taken to improve.

PHCPI-authored cases were developed via an examination of the existing literature. Some also feature key learnings from in-country experts.

- East Asia & the Pacific

- Europe & Central Asia

- Latin America & the Caribbean

- Middle East & North Africa

- North America

- South Asia

-

- Bangladesh: Using DHIS2 to improve the integration and interoperability of HIS

- Nepal: Strengthening PHC capacity in the public sector through an integrated health information system in Nepal

- Rajasthan, India: Utilizing digital health technology for COVID-19 response and ensuring access to essential health services in Rajasthan, India

- Sri Lanka: Ensuring access to routine and essential services during COVID-19 through utilizing telehealth in Sri Lanka

- Sub-Saharan Africa

-

- Ethiopia: Strengthening Primary Health Care Systems to Increase Effective Coverage and Improve Outcomes in Ethiopia

- Kenya, Tanzania, and Zambia: Case study series - community-based information systems

- Multiple countries: Integrated disease surveillance and response

- Multiple countries: The community of practice health delivery: strengthening knowledge sharing to accelerate PHC improvement in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Multiple regions

-

- Multiple countries: Case studies on data innovations for strengthening PHC

- Multiple countries: 8 Core Tenets of Primary Health Care Improvement in Middle and High-Income Countries

- Bangladesh, Colombia, Rwanda, and Viet Nam: How champions in four countries are working toward counting everyone via timely, complete CRVS

- Nepal, Malawi, and Kenya: Community health worker-based surveillance in resource-constrained contexts

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Building consensus on what information & technology is and key strategies to fix gaps is an important step in the improvement process.

Below, we define some of the core characteristics of information & technology in greater detail:

-

Effective health information systems are comprehensive, capturing data about health services at all levels of the health system. However, often health information systems lack data about PHC or do not enable data to be disaggregated by type or level of service. In order for health information systems to support PHC as described above, it is critical that they not only embody the characteristics of strong information systems but that they also include PHC-specific indicators, such as those included in the PHC Vital Signs Profile, and be designed in a way that enables disaggregation of data to track the capacity and performance of PHC specifically. The Joint Learning Network and PHCPI’s guide on measuring the performance of PHC provide practical guidance and tools for countries on how to do so.

Well-functioning health information systems yield high-quality and comprehensive data and information essential for enabling effective and priority setting, population health management, facility management, and the achievement of the core functions of PHC, including , , comprehensiveness, and person-centeredness. WHO identifies four core functions achieved by health information systems: 35

- Data generation: Data are recorded by health and other relevant sectors.

- Data compilation: Data are collected and organized from health and other relevant sectors.

- Analysis and synthesis: Data are checked for overall quality, relevance, and timeliness, and subsequently analyzed as needed.

- Communication and use: Data are converted into information for health-related decision-making in formats that meet the needs of multiple users (i.e. policymakers, managers, providers, and communities) and used to drive decision-making and planning.

This module focuses specifically on the data generation and compilation functions of information systems. The analysis and synthesis functions and communication and use functions are discussed more fully in the Adjustment to Population Health Needs module. Information system use at the facility level is discussed in the Management of Services module.

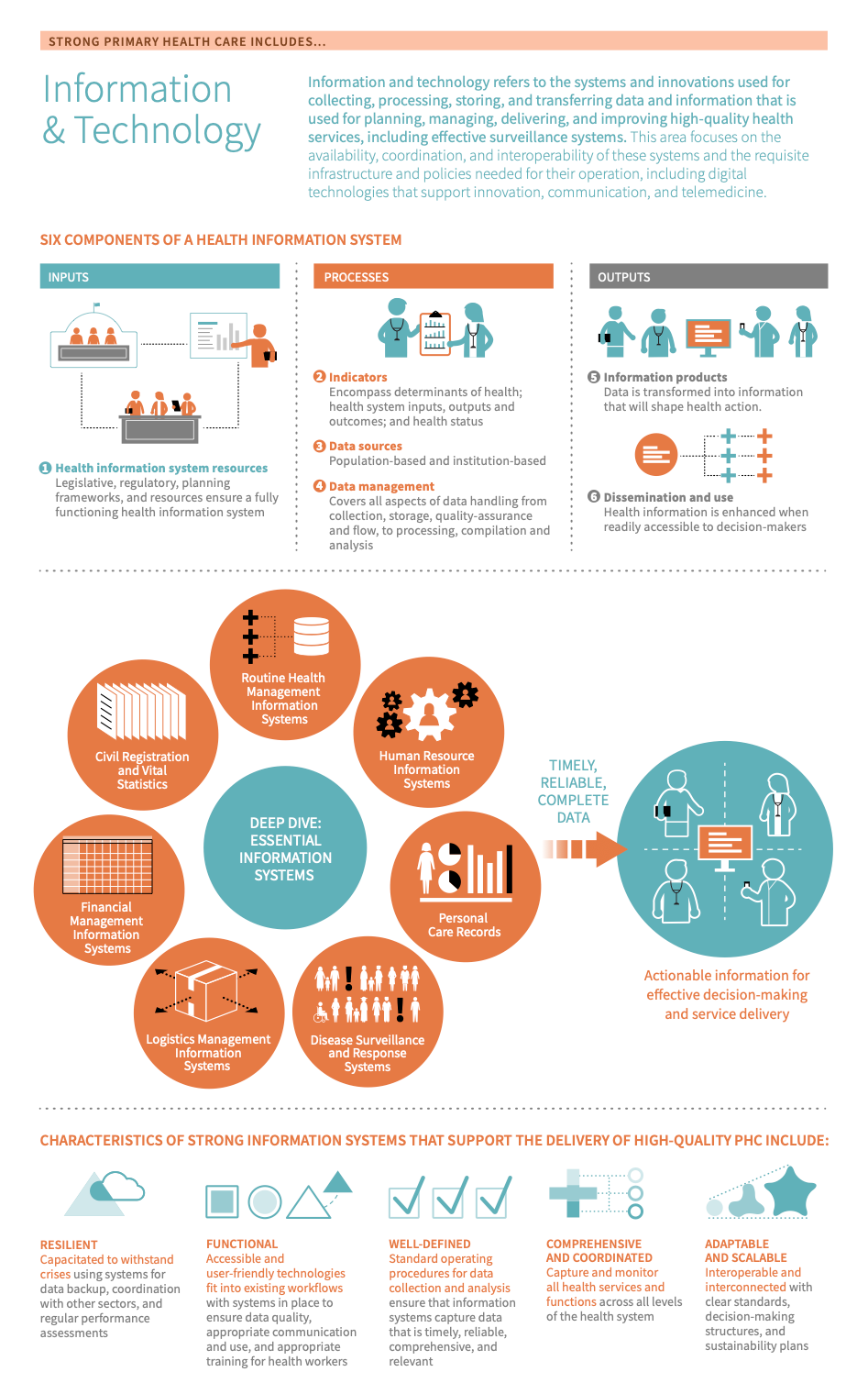

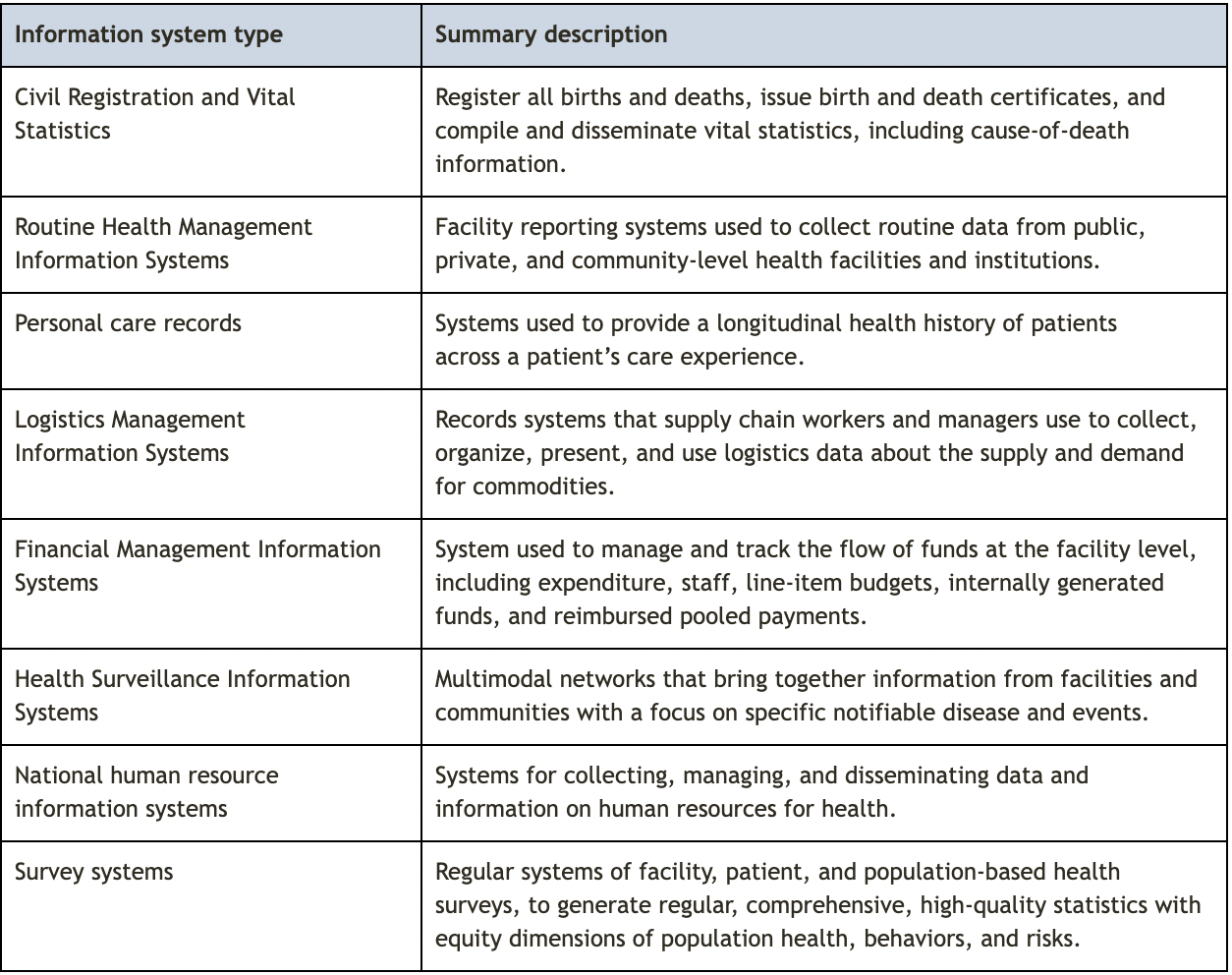

Essential types of information systems

The following eight types of information systems are essential for the delivery of high-quality PHC. As described below, each type of system plays a critical role in ensuring that the right type of data is available to the right stakeholders at the right time to make informed decisions about PHC planning and service delivery.

Civil Registration and Vital Statistics

Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) systems are a type of information system that registers all births and deaths, issues birth and death certificates, and compiles and disseminates vital statistics, including cause-of-death information, and are typically housed in a country’s national statistics agency. CRVS systems may also record other events such as marriage, divorce, adoption and legitimation. CRVS systems generate administrative data that are used across multiple sectors and which can be compiled to serve as the basis for databases such as population registers that play a vital role in PHC service delivery. CRVS systems provide routine, up-to-date fertility and mortality data for a population which can be used to establish the foundation for many health policies and provides a meaningful denominator for monitoring and evaluation of the burden of disease data. CRVS systems are particularly critical for ensuring that PHC systems can adjust to population health needs and for effective population health management. 36

Routine Health Management Information Systems

Health Management Information Systems (HMIS) are facility reporting systems used to collect routine data from public, private, and community-level health facilities and institutions managed by national ministries of health. Well-designed HMIS provide data on health status, health services, and health resources at the health facility level that can be used to support evidence-informed planning, management, and decision-making at the facility and administrative levels. 353738 This goes beyond simple monitoring and evaluation to facilitate the active collection and assessment of . HMIS systems should be integrated into a national and subnational monitoring framework built on a standardized list of service delivery indicators and definitions, called a .

Personal care records

Personal care records are information systems that are used to provide a longitudinal health history of patients to facilitate the provision of high-quality PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. , typically provided by health plans and health care providers. Comprehensive personal care records include unique patient identification, problem lists, care history and notes, medication lists and allergies, referrals and results of referrals, and laboratory, radiology, and other test results. 394041 Well-designed personal care record systems continuously collect and coordinate information that is reliable, timely, up-to-date, and comprehensive. Personal care records can be paper-based or electronic, however, the use of records helps to improve the management of patient care. Regardless of the format used, to empower patients and health care providers to ensure the delivery of high-quality person-centred care, personal care records must be sufficiently accessible to both patients and providers. 40

Logistics Management Information Systems

Logistic Management Information Systems (LMIS) are records systems that supply chain workers and managers use to collect, organize, present, and use logistics data about the supply and demand for commodities. Health LMIS are typically managed by countries’ ministries of health. Logistics data include information about the quantification, procurement, inventory management, and storage and transportation of essential medicines and supplies. Effective LMIS gather data across all levels of the health system to support informed decision-making and supply chain management. 4243

Financial Management Information Systems

Financial Management Information Systems (FMIS) are used to manage and track the flow of purchasing and payments at the facility level, including expenditure, staff, line-item budgets, internally generated funds, and reimbursed pooled payments, usually housed in a country’s finance ministry. They are facility-level tools managers use to improve the strategic allocation of resources, minimize waste, and align spending for operational efficiency, establish credibility of the budgets, and improve service delivery. 44

Health Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. Information Systems

Health Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. Information Systems generate the information needed for effective surveillance, including detecting, reporting, and responding to specific notifiable conditions and events and are typically managed by a country’s health agency. 45 Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. systems are multimodal networks that bring together information from facilities and communities with a focus on defining emerging and existing population health needs and providing a basis for timely and appropriate response across the health system. 26343539

National human resource information systems

National human resource information systems (HRIS) are essential for generating, managing, and disseminating key required human resources and health workforce information, critical for countries aiming to achieve universal health coverage. National human resource information systems for health are typically managed through a country’s health ministry. These systems integrate data on workers across public, private, and government health facilities as well as non-facility-based service providers; track all categories of health professions and health system support staff; and provide some of the information necessary for prioritizing and allocating resources needed for health worker training and deployment to achieve the goals of a health system. 4647 In support of this, the National Health Workforce Accounts is a system that has been developed to aid countries in progressively improving the availability, quality, and use of health workforce data. 48

Survey system

Survey systems can be composed of regular facility-, patient-, and population-based health surveys. These surveys are meant to generate regular, comprehensive, high-quality statistics, with equity dimensions, of population health, behaviours, and risks. Facility and patient surveys enable independent monitoring of health services and patient perspectives, essential for quality improvement, risk mitigation, patient safety, and improvements to efficiency and accountability. 13 Population-based health surveys are key for measures of health status – including mental health and well-being, health behaviours and risk factors, and access to health interventions and out-of-pocket spending on health at the population level. Population surveys are important to facilitating measures of equity as they are typically designed to be able to disaggregate data by demographics, for example by sex, age, education, or income. Population-based surveys can capture a broader sample of the population than facility-based or patient surveys, as those by definition target individuals using health care services. As such, population-based surveys can provide a better understanding of a country’s burden of disease and risk factors. 13

Components and standards of information systems

According to the WHO, there are six components of a health information system, which can be divided into inputs (e.g. health information systems), processes (e.g. indicators, data sources, and data management), and outputs (e.g. information products, dissemination, and use). These are described below. 49

Source: Adapted from the 2012 WHO Framework and Standards for Country Health Information Systems

Strong information systems are resilient, functional, well-defined, adaptable, and scaleable

The most effective information systems are entirely interoperable and interconnected: 82250

- is the ability of different information systems, processes, devices, or applications to connect, in a coordinated manner, within and across organizational or geographic boundaries to access, exchange, and cooperatively use data amongst stakeholders, with the goal of optimizing the health of individuals and populations. 51

- refers to the facilitated linkage or connection of all constituent parts of the information system. This refers to the connection of information system components—data systems, detection, reporting, and investigative activities, and feedback loops—within a subnational health system network, and the linkage between different subnational health system networks.

Information systems can be either paper-based or electronic, however, there is an increasingly global move toward the efficiency and accessibility of electronic systems. While much can be accomplished with paper-based systems, it is difficult to achieve interoperability and interconnectedness with exclusively paper-based systems. 52 To promote the development of information systems that are comprehensive, reliable, scaleable, accessible, interoperable, and interconnected, countries should work to move from paper-based to electronic systems. 5253 Users can find more information about digital and e-health strategies below or in the National eHealth Strategy Toolkit and the WHO’s Global Strategy on Digital Health. 1654

The transition from paper-based to electronic information systems represents an ambitious goal for many countries. In the interim, there are many important improvements that can be made even to paper-based systems. In particular, there are five general characteristics common to strong information systems that support the delivery of high-quality PHC that can be achieved regardless of whether the systems are electronic: 55

- Well-defined: To ensure that information systems capture timely, reliable, comprehensive data relevant to the needs of the population, information systems should be implemented with standard operating procedures for data collection and analysis. This includes using standard data sources and data dictionaries that define a standardized list of that are built into national or subnational monitoring frameworks, to ensure that all users of the information system are defining and measuring indicators in the same way. 39

- Comprehensive: To support the core principles of coordination, continuity, comprehensiveness, and patient-centeredness, information systems should comprehensively capture and monitor all health services and functions across all levels of the health system.

- Functional: To ensure that information systems are consistently used to support effective decision-making for health, their design and functionality should:

- Be accessible and user-friendly for all levels of the health workforce,

- Fit efficiently and intuitively into existing workflows,

- Use technology appropriate for the context, and

- Have plans and systems in place to ensure data quality, appropriate data communication and use, and appropriate training for health workers.

- Resilient: To support the capacity of the health system to adapt and respond to population health needs, information systems should be able to withstand social, political, and biological crises. Mechanisms such as data backup systems and systems for operationalizing learnings from past crises, coordination with other health system functions, and regular performance assessments help to build resilient information systems. 3

- Adaptable and scalable: A strong information system is adaptable and scalable; it is able to be redesigned, reformed, expanded, and rolled out at all levels of the health system. Information systems that are readily adaptable and scalable embody the above four characteristics and are interoperable and integrate with existing in-country platforms. Additionally, adaptability and scalability depend on having clear standards and decision-making structures regarding health information systems and a well-defined sustainability plan for ensuring necessary financing for, training in, and monitoring and evaluation of the system. Read more about building in-country capacity in MEASURE Evaluation’s characteristics of a strong health information system.

Strengthening information systems requires leadership and good management, governance of policies and procedures, public trust, financial support, and a skilled workforce. 55 For this reason, it is important that information systems are aligned with national priorities and local needs with a clear policy direction, financial support, and skills training to ensure their successful implementation and ongoing functionality. 5657 More information on developing strong information systems can be found in the Take Action section of this module.

-

Digital technologies for health include a broad range of components from the use of software as a medical device, medical device data systems and interoperability, cybersecurity, health IT, wireless medical devices, and . 3358

- E-Health is the use of information and communication technologies for health. 59 It involves various activities that use electronic means to deliver health-related information, resources, or services.

- Telehealth refers to the use of information and communications technologies to support the delivery and management of remote health care services. Telehealth activities may include long-distance health care, patient and provider health-related education, public health, and health care management. Two common forms of telehealth are telemedicine – the delivery of remote clinical services (see more below) – and remote patient monitoring – the use of electronic devices to report, collect, transmit, and evaluate patient health data outside traditional health care settings. Telehealth can be delivered through a variety of different technologies including mobile phones, smartphone applications, landlines, videoconferencing, portable electronic devices, wearable technology, and store-and-forward imaging. 606162

- Telemedicine “The delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by use all health care professionals using information and communications technologies for the exchange of valid information for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and the continuing education of health care workers, with the aim of advancing the health of individuals and communities.” : Many people do not have adequate access to health care either due to geography, physical or financial barriers or from being in a vulnerable or stigmatized group. Increasing access to these populations is an important step towards universal access. Virtual health consultations, also known as telemedicine, do so using information and communication technologies including web applications and devices that are increasingly available across populations. 5460 Telemedicine “The delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by use all health care professionals using information and communications technologies for the exchange of valid information for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and the continuing education of health care workers, with the aim of advancing the health of individuals and communities.” is also a tool for health education for communities and individuals training to become health care workers. It is an important component of a country’s e-health strategy, discussed more in the Take Action section of this module. 16

-

Effective surveillance hinges on consistent access to reliable, real-time data that capture a comprehensive range of information on population health needs and events of public health significance. 256364 As countries undergo epidemiological transitions, surveillance systems must be equipped to track a broad spectrum of communicable and non-communicable diseases to meet global targets and ensure comprehensive disease surveillance. 646566 Effective surveillance systems consistently perform the following functions: 62767

- Track health and burden of disease metrics (morbidity, mortality, incidence)

- Detect, report, and investigate notifiable diseases, events, symptoms, and suspected outbreaks or extraordinary occurrences

- Continuously collect, collate, and analyse the resulting data

- Submit timely and complete reports from local to higher levels of the system and from higher levels of the system back to lower/community levels

In addition to collecting data on the incidence of communicable diseases of public health significance and subsequent notification of emergency response systems, effective surveillance systems also collect comprehensive information on other elements of population health to inform service delivery. For example, an effective surveillance system would be designed to detect, report, and investigate an incident of viral meningitis, as well as flag a slow-building increase in diabetes complications, or seasonal increase in road traffic injuries.

To be an effective first point of contact, PHC must be able to consistently deliver services that users trust, value, and can easily access. 6869 As this first point of contact, PHC settings are critical sources of information and data for surveillance and response efforts, including maintaining routine service delivery and preventing disease outbreaks through the gathering of data, detecting and diagnosing conditions, alerting surveillance systems to trigger subsequent response, and providing case management at the primary care level. 770 A continuous feedback loop should be in place across all health system levels to ensure that information informs action and improves routine service delivery activities. The information generated from surveillance and response efforts at the PHC level, including lessons learned from past responses to outbreaks, should be integrated into the broader surveillance system for continuous strengthening of the health system.

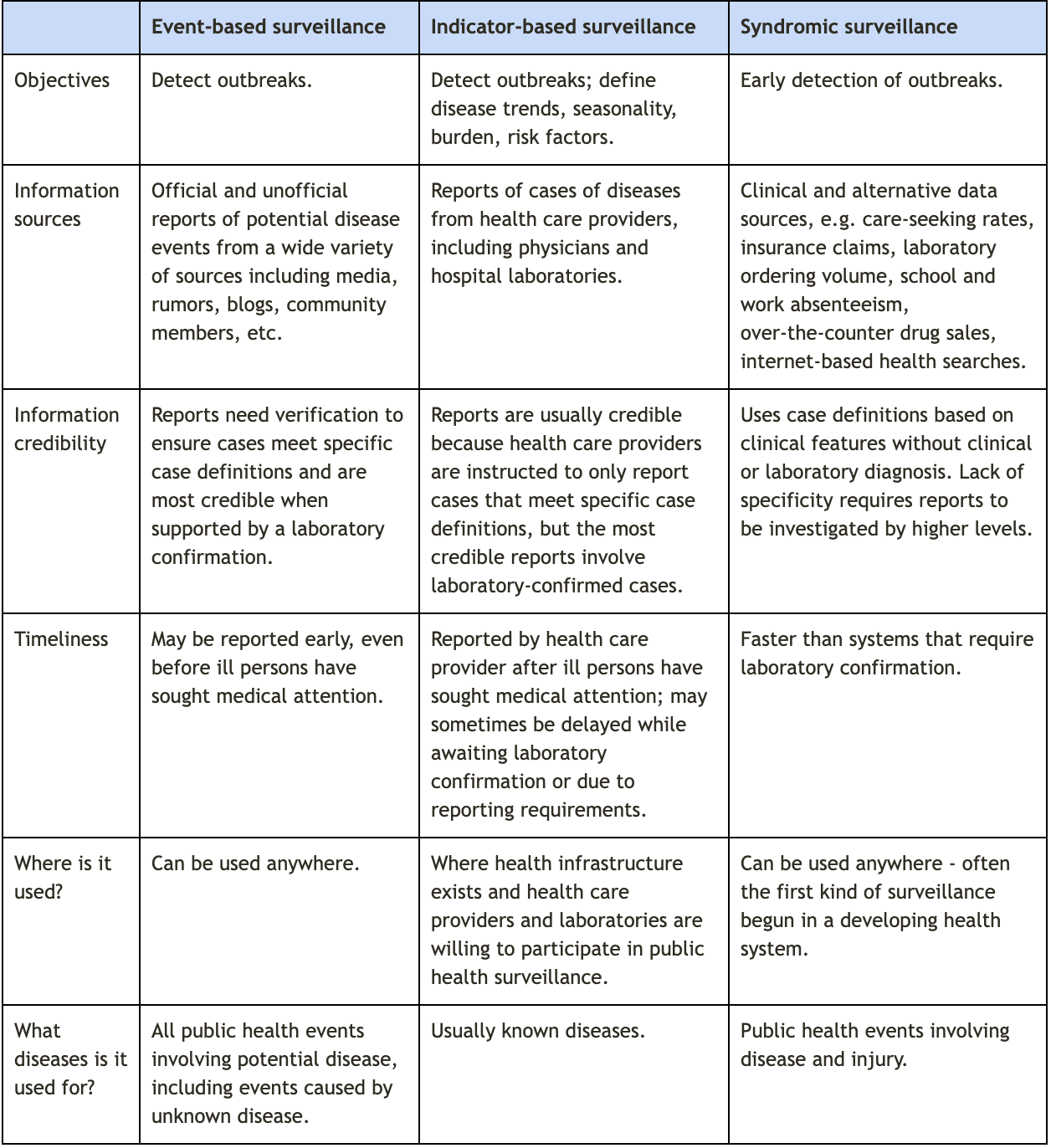

Types of surveillance

Three types of surveillance are essential for effective adjustment to population health needs: 272871

Indicator-based surveillance

Indicator-based surveillance is the systematic collection, monitoring, analysis, and interpretation of data produced by formal or traditional information sources. Formal sources include official or authorized sources in direct contact with the event, such as primary care facilities and hospitals, clinicians, and local laboratories. 72

Event-based surveillance

Event-based surveillance refers to the organized and rapid collection, monitoring, assessment, and interpretation of mostly ad-hoc information about events that pose a potential risk to public health. These data typically come from informal sources, such as the media, social network channels, and other crowd-sourced information. Event-based systems are often designed to be complementary to traditional indicator-based surveillance systems. They are meant to enhance the capacity of the national surveillance system to detect a more comprehensive set of public health threats, including rare and new events not included in indicator-based surveillance, and events that occur in populations who access care through informal or non-traditional channels. Strengthening event-based surveillance is discussed more in the WHO’s Guide to Establishing Event-Based Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. and the WHO report on early detection, assessment and response to acute public health events: implementation of early warning and response with a focus on event-based surveillance. 7273

Syndromic surveillance

Syndromic surveillance is a method of surveillance that aims to detect outbreaks earlier than traditional methods by focusing “on the early symptom period before clinical or laboratory confirmation of a particular disease,” 74 and using both clinical and alternative data sources such as care-seeking rates, insurance claims, laboratory ordering volume, school and work absenteeism, over-the-counter drug sales, community reporting, and internet-based health searches.

Table 1. essential types of surveillance

Adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webpage on global health protection and security: event-based surveillance and from Public Health Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. : A Tool for Targeting and Monitoring Interventions, in Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd edition.

Effective surveillance systems perform the four core functions:

- Track health and burden of disease metrics (morbidity, mortality, incidence)

- Detect, report, and investigate notifiable diseases, events, symptoms, and suspected outbreaks or extraordinary occurrences

- Continuously collect, collate, and analyze the resulting data

- Submit timely and complete reports from local to higher levels of the system and from higher levels of the system back to lower/community levels

The following questions may be useful for assessing performance across these functions, determining whether surveillance is an appropriate area of focus for a given context, and how one might begin to plan and enact reforms.

How reliable is your surveillance system?

Effective surveillance systems detect and track a broad spectrum of data on communicable and non-communicable diseases and events from both formal and informal reporting sources. To enable this, comprehensive surveillance systems integrate indicator-based, event-based, and syndromic surveillance strategies.

To understand how comprehensive your surveillance system may be, you might consider the strengths and weaknesses of the different types of surveillance strategies included in your surveillance system and the information collected and reported by these systems. How are the different surveillance strategies used? If not all types of surveillance are being fully utilized, are there plans in place to develop or enhance these strategies? What types of data sources are used (i.e. facility-based or informal)? Are these systems interoperable and interconnected?

How are reports made and how reliable and timely are these reports?

Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. systems must submit timely and complete reports from local to higher levels of the system and from higher levels of the system back to sub-national levels. To understand where gaps in your surveillance system may be, you might consider looking at recent examples of surveillance reporting. How were reports made? Are they reliably sent? If not, are gaps due to problems with information systems, workforce training, policies, or other factors?

How reliably and successfully have follow-up investigations been made?

Effective surveillance systems should produce reliable, high-quality, and accessible data, reports, and analyses of trends in priority diseases, with benchmarks to track effectiveness. These outputs of surveillance should be continuously documented with proof of alerts being triggered, followed up, and validated. If follow-up investigations to alerts are not being made, stakeholders should identify and seek to understand why there are gaps. Are interoperable, interconnected, and electronic communication channels and information systems in place to produce data and reports and analyze trends? Are these consistently functioning? If not, are gaps due to problems with workforce training, policies, or other factors?

Information systems support surveillance

Effective surveillance systems use data to quickly and effectively identify emerging threats and continuously assess and respond to communities’ needs over time. 34 However, collecting and recording data has little use without mechanisms in place to detect incidences or trends, specific communication channels for reporting, and trained staff with the necessary expertise to investigate and respond to these incidences or trends. The establishment of feedback loops for communication between the national and community level is particularly important for timely response to incidents as well as for the overall integration of the surveillance system into service delivery at the facility and community level. 2325

The most effective information systems are entirely electronic, interoperable, and interconnected. 82275 This in turn allows stakeholders to respond to disease instances, with the goal of optimizing the health of individuals and populations. 50

High-performing information systems enable:

- The continuous collection of data on diseases and events of public health significance (including burden of diseases data) from both traditional (indicator-based) sources and non-traditional sources, such as community-based or crowd-sourced data. 25636476 More information on collecting data from non-traditional sources can be found in the WHO’s guide for establishing community-based surveillance. This information should inform planning for future and ongoing community needs at the facility level and in the community, such as through proactive population outreach activities.

- Systematic and timely reporting from local to higher levels of the system and from higher levels of the system back to subnational levels. Feedback loops between facilities, subnational regions, and the centralized levels of the health system are critical to ensure that the data actually informs action. The flow of information from the national level back to facilities is particularly important for response to incidents, as well as for the overall integration of the surveillance system into population health and facility management.

- Linkages to laboratory and other information systems and coordination with actors in other relevant sectors to provide a complete surveillance picture. More information on strengthening health systems through coordination can be found in the WHO Framework for Action Toward Coordinated/Integrated Health Services Delivery and the World Bank report on Health Reform in China. 7778

- Timely analysis of surveillance data by designated data analysis teams.

- Timely reporting of surveillance data by designated reporting teams.

Communication systems should promote feedback systems between facilities, subnational regions, and the centralized levels of the health system. Relevant health workers must be appropriately trained and have a clear understanding of communication channels for reporting as well as the processes for investigating and responding to reports.

Users can access more information on improving the quality, availability, analysis, use, and accessibility of data in SCORE for health data, a technical package of essential interventions, actions, tools, and resources that aim to improve health information systems in countries. (79) Additionally, users can find more information on developing well-functioning information systems in the WHO’s handbook on Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: Information Systems and their Strategic Framework for Effective Communications.(80,81)

Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. systems rely on communication and trust

To capture relevant and up-to-date information on population health needs, surveillance systems must be able to continuously collect and track information from formal sources, such as health facilities, as well as informal sources, such as community-based or crowd-sourced data. Collecting and tracking information on population health needs relies on public use and confidence in the health system. From the patient perspective, utilization of the health system is influenced by access (timely, geographic, and financial) and acceptability (including the trust and value placed in services). Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. systems that leverage approaches to enhance access and public trust in service delivery, including proactive population outreach and community engagement, gather more accurate data and strengthen the capacity of the health system to effectively monitor and respond to health needs in emergencies and over time.

Effective, regular, and inclusive communication and coordination between stakeholders at all levels of the health system, including the community and the private sector, is critical for ensuring that all relevant actors are included at the right time. To support a transparent and participatory engagement process, there should be established processes for engaging key national, regional, local, and international stakeholders with a clear definition of roles, sharing of resources, and joint action plans. Users can find more information in the Internal and Partner Communication and Coordination Coordinated care includes organizing the different elements of patient care throughout the course of treatment and across various sites of care to ensure appropriate follow-up treatment, minimize the risk of error, and prevent complications. Coordination of care happens across levels of care as well as across time, and often requires proactive outreach on the part of health care teams as well as informational continuity. and Public Communication indicators of the WHO’s Joint External Evaluation Tool. 27

More information on coordination activities and broad approaches to improving the delivery of care can be accessed in the Care Coordination Coordinated care includes organizing the different elements of patient care throughout the course of treatment and across various sites of care to ensure appropriate follow-up treatment, minimize the risk of error, and prevent complications. Coordination of care happens across levels of care as well as across time, and often requires proactive outreach on the part of health care teams as well as informational continuity. Measures Atlas from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 85

Because many stakeholders are involved in surveillance, it’s critical to facilitate trust among different levels of the health system, the public, the media, and the non-health sectors. Communication systems might include partnerships between the government and diverse media outlets to provide health advice and address misinformation to the public in a factual and accessible manner. Users can find more information on building public communication, listening, and rumour management systems in the Risk Communication indicator of the WHO’s Joint External Evaluation Tool. 27

-

- Continuity “Continuity is the degree to which a series of discrete healthcare events are experienced as coherent and connected and consistent with the patient’s medical needs and personal context.” Three types of continuity are considered to be important for primary care: relational continuity, informational continuity, and management continuity. : “ Continuity “Continuity is the degree to which a series of discrete healthcare events are experienced as coherent and connected and consistent with the patient’s medical needs and personal context.” Three types of continuity are considered to be important for primary care: relational continuity, informational continuity, and management continuity. is the degree to which a series of discrete healthcare events are experienced as coherent and connected and consistent with the patient’s medical needs and personal context.” Three types of continuity are considered to be important for primary care: relational continuity, informational continuity, and management continuity. 8

- Coordination Coordinated care includes organizing the different elements of patient care throughout the course of treatment and across various sites of care to ensure appropriate follow-up treatment, minimize the risk of error, and prevent complications. Coordination of care happens across levels of care as well as across time, and often requires proactive outreach on the part of health care teams as well as informational continuity. : Coordinated care includes organizing the different elements of patient care throughout the course of treatment and across various sites of care to ensure appropriate follow-up treatment, minimize the risk of error, and prevent complications. Coordination Coordinated care includes organizing the different elements of patient care throughout the course of treatment and across various sites of care to ensure appropriate follow-up treatment, minimize the risk of error, and prevent complications. Coordination of care happens across levels of care as well as across time, and often requires proactive outreach on the part of health care teams as well as informational continuity. of care happens across levels of care as well as across time, and often requires proactive outreach on the part of health care teams as well as informational continuity. 86

- Data architecture “Health information system architecture describes the fundamental organization of the system embodied in its components, standards, and principles governing its design and evaluation.” : “Health information system architecture describes the fundamental organization of the system embodied in its components, standards, and principles governing its design and evaluation.” 87

- Data confidentiality Data confidentiality means that “health information is not made available or disclosed to unauthorized persons or processes.” : Data confidentiality Data confidentiality means that “health information is not made available or disclosed to unauthorized persons or processes.” means that “health information is not made available or disclosed to unauthorized persons or processes.” 88

- Data dictionary A data dictionary is made up of a standardized list of indicators and definitions that are built into a national or sub-national monitoring framework to ensure that all users of an HMIS are defining and measuring indicators in the same way. : A data dictionary is made up of a standardized list of indicators and definitions that are built into a national or subnational monitoring framework to ensure that all users of an HMIS are defining and measuring indicators in the same way. 39

- Electronic health (e-health): “E-Health involves a broad group of activities that use electronic means to deliver health-related information, resources and services: it is the use of information and communication technologies for health.” 59

- Health indicators Health indicators are quantifiable characteristics of a population that provide information on the population health situation, such as information related to health status, risk factors, service coverage, and health systems (i.e. quality and safety of care or utilization and access). : Health indicators Health indicators are quantifiable characteristics of a population that provide information on the population health situation, such as information related to health status, risk factors, service coverage, and health systems (i.e. quality and safety of care or utilization and access). are quantifiable characteristics of a population that provide information on the population's health situation, such as information related to health status, risk factors, service coverage, and health systems (i.e. quality and safety of care or utilization and access). 89

- Interconnectedness Interconnectedness refers to the facilitated linkage or connection of all constituent parts of the information system. This refers to the connection of information system components—data systems, detection, reporting, and investigative activities, and feedback loops—within a sub-national health system network, and the linkage between different sub-national health system networks. : Interconnectedness Interconnectedness refers to the facilitated linkage or connection of all constituent parts of the information system. This refers to the connection of information system components—data systems, detection, reporting, and investigative activities, and feedback loops—within a sub-national health system network, and the linkage between different sub-national health system networks. refers to the facilitated linkage or connection of all constituent parts of the information system. This refers to the connection of information system components—data systems, detection, reporting, and investigative activities, and feedback loops—within a subnational health system network, and the linkage between different subnational health system networks. 39

- Interoperability Interoperability is the ability of different information systems, processes, devices, or applications to connect in a coordinated manner, within and across organizational or geographic boundaries to access, exchange and cooperatively use data amongst stakeholders to respond to disease instances, with the goal of optimizing the health of individuals and populations. : Interoperability Interoperability is the ability of different information systems, processes, devices, or applications to connect in a coordinated manner, within and across organizational or geographic boundaries to access, exchange and cooperatively use data amongst stakeholders to respond to disease instances, with the goal of optimizing the health of individuals and populations. is the ability of different information systems, processes, devices, or applications to connect in a coordinated manner, within and across organizational or geographic boundaries to access, exchange, and cooperatively use data amongst stakeholders to respond to disease instances, with the goal of optimizing the health of individuals and populations. 51

- Service data “Service data are data generated at the facility level and include key outputs from routine reporting on the services and care offered and the treatments administered.” : “ Service data “Service data are data generated at the facility level and include key outputs from routine reporting on the services and care offered and the treatments administered.” are data generated at the facility level and include key outputs from routine reporting on the services and care offered and the treatments administered.” 35

- Surveillance The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. : The ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery and public health. 4527

- Telemedicine “The delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by use all health care professionals using information and communications technologies for the exchange of valid information for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and the continuing education of health care workers, with the aim of advancing the health of individuals and communities.” : “The delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by use all health care professionals using information and communications technologies for the exchange of valid information for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and the continuing education of health care workers, with the aim of advancing the health of individuals and communities.” 54

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

References:

- Yazdi-Feyzabadi V, Emami M, Mehrolhassani MH. Health Information System in Primary Health Care: The Challenges and Barriers from Local Providers’ Perspective of an Area in Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2015 Jul 6;6:57.

- MEASURE Evaluation. Defining Health Information Systems [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 29]. Available from: https://www.measureevaluation.org/his-strengthening-resource-center/his-definitions/defining-health-information-systems

- World Health Organization. Framework and Standards for Country Health Information Systems - Second Edition. 2012 [cited 2020 May 29]; Available from: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/country_monitoring_evaluation/who-hmn-framework-standards-chi.pdf