|

|

|

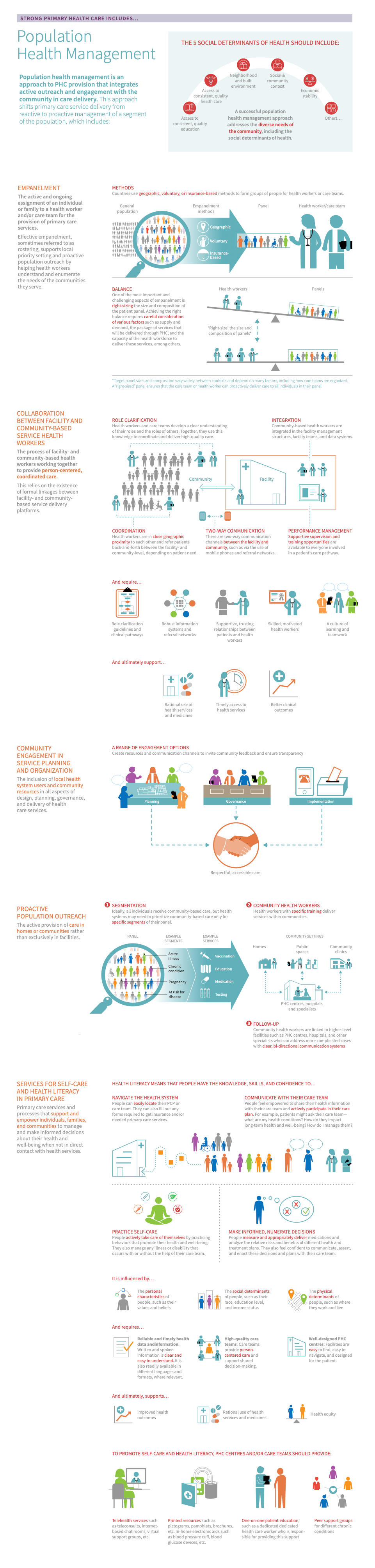

Population health management is a core component of high-quality health systems and when done effectively, promotes the development of strategies and plans that emphasize access, high-quality PHC, effective service coverage, health status, responsiveness to people, equity, and resilience of health systems.

Inherent in population health management is the provision of a broad range of health activities including curative and preventive care, health promotion activities delivered through broad public health initiatives, and engagement with social determinants of health.

Population Health Management (PHM) is an approach to PHC provision that integrates active outreach and engagement with the community in safe and high-quality care delivery, as well as planning and decision-making at the local level. This approach shifts primary care service delivery from reactive to proactive management of different segments of the population. Key components of population health management include:

- Empanelment is the active and ongoing assignment of an individual or family to a primary care provider and/or care team for the provision of primary care services. Empanelment establishes a point of care for individuals and simultaneously holds providers and care teams accountable for actively managing care for a specific group of individuals. Empanelment also provides a population denominator so stakeholders can more easily interpret data, track performance, and effectively plan services. 1

- Collaboration between facility and community-based service providers is the process of facility- and community-based providers working together to provide person-centred, coordinated care. Depending on patient needs and preferences, care may be delivered in the home, community, or facilities. This process helps to ensure that patients can access a more comprehensive set of services when they need it most and informational continuity between a patient’s care team. 234

- Community engagement Community engagement is the inclusion of local health system users and community members in all aspects of health planning, provision, and governance. It is a central component of ensuring that the services delivered are tailored to population needs, priorities and values, which can be achieved through the involvement of communities in the design, financing, governance, and implementation of PHC. To ensure that the needs of all community members are met, it is important that community engagement efforts include representation from diverse members of the community. This may require multiple mediums for engagement, to best capture the needs and opinions of traditionally underrepresented community members. in service planning and organization refers to the inclusion of local health system users and community resources in all aspects of design, planning, governance, and delivery of health care services. Community engagement Community engagement is the inclusion of local health system users and community members in all aspects of health planning, provision, and governance. It is a central component of ensuring that the services delivered are tailored to population needs, priorities and values, which can be achieved through the involvement of communities in the design, financing, governance, and implementation of PHC. To ensure that the needs of all community members are met, it is important that community engagement efforts include representation from diverse members of the community. This may require multiple mediums for engagement, to best capture the needs and opinions of traditionally underrepresented community members. is a central component of effective population health management and helps ensure that services are appropriately tailored to population needs and values. Service planning and organization activities often include local priority setting--which refers to the process of identifying health priorities specific to the local community and developing action plans informed by community needs as well as national or regional priorities. To ensure that all community needs are met, it is important that community engagement efforts include representation from a diverse set of community members. 56

- Proactive population outreach is the active provision of care in homes or communities rather than exclusively in facilities. These services are often preventive or promotive and initiated by the health system rather than by patients. Community health workers or similar cadres of providers most often engage in proactive population outreach and conduct health promotion activities, education, identification of acute cases and pregnant women needing referrals to health facilities, community-integrated care for common adult and child illnesses, family planning provision, chronic disease adherence follow-up, risk-stratified care management, and even palliative care in communities or homes.

- Services for self-care and health literacy in primary care are primary care services and/or processes that support and empower individuals, families, and communities to manage their health and well-being when not in direct contact with health services. Such services include actions to improve a patient and/or community’s ability to improve their health, including via the achievement of a certain level of knowledge, skills and confidence to change their lifestyle and living conditions.7 Services for self-care and health literacy often include the use of telehealth, printed educational resources, in-home electronic aids (i.e. blood pressure cuff, blood glucose device), one-on-one patient education, and established peer support groups.6

Effective PHM typically occurs both in established clinics and in the community. It requires a strong organizational structure, efficient information systems, and an appropriate mix and a sufficient quantity of providers. Inherent in population health management is the provision of a broad range of health activities including curative and preventive care, health promotion activities delivered through broad public health initiatives, and engagement with social determinants of health.

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Before taking action, countries should first determine whether population health management is an appropriate area of focus and where to target improvement efforts. Read on to learn how to use country data to:

- Make informed decisions about where to spend time and resources

- Track progress and communicate these updates to constituents or funders

- Gain new insights into long-standing trends or surprising gaps

Countries can measure their performance using the Vital Signs Profile (VSP). The VSP is a first-of-its-kind tool that helps stakeholders quickly diagnose the main strengths and weaknesses of primary health care in their country in a rigorous, standardized way. The second-generation Vital Signs Profile measures the essential elements of PHC across three main pillars: Capacity, Performance, and Impact. Population health management is measured in the Management of Services and Population Health domain of the VSP (Performance Pillar).

If a country does not have a VSP, they can begin to focus improvement efforts using the subsections below, which address:

- Key indications

-

If your country does not have a VSP, the indications below may help you to start to identify whether population health management is a relevant area for improvement:

- Overuse of speciality and/or hospital services: if a PHM approach is not in place it may lead to the overuse of speciality or emergency services for conditions that can be managed at the primary care level--commonly referred to as ambulatory care sensitive conditions. For example, if no system for empanelment is in place, patients who do not have a usual source of care may bypass local facilities and/or seek unnecessary speciality or emergency services that are more convenient or known to them.89

- Inefficient, ineffective care such as long wait times and/or delayed follow-up visits: if a provider’s caseload is not balanced, such as via a system for empanelment, and care is not proactive it may contribute to long wait times, provider burnout, poor follow-up, and other inefficiencies in service delivery.89

- Poor self-reported heath status and health outcomes: if care is not proactive (i.e. patients don’t receive preventative care), tailored to local needs, and/or patients do not feel supported and empowered to manage their health, it may lead to worse patient-reported outcome measures and poor health outcomes more generally.89

- High rates of patient distrust and/or poor patient experience measures: if patients bypass primary care services and/or report distrust in providers or local facilities, it may indicate that patient voices are being excluded and/or underutilised in service delivery and reform is needed. It may also indicate that care is not meeting the needs of patients.89

- Key outcomes and impact

-

Countries that improve population health management may achieve the following benefits or outcomes:

- Universal health coverage: by bringing services directly to communities, community-based care and other outreach activities help to ensure that all patients can access needed care when they need it most. Furthermore, a proactive approach to service delivery can support the provision of a broader range of health activities, including curative, promotive, and preventive care.6910111213

- Adjustment and accountability to population health needs: a PHM approach helps countries to actively engage with local communities, hold providers accountable to the needs of these communities, and plan targeted outreach activities that adapt to community needs over time.6910111213

- Improved patient experience and health outcomes: it also enables care teams to better understand and enumerate the needs of the communities they serve, which can help to build trust and respect between patients and providers and increase patient utilization of needed services. In addition, services for self-care and health literacy can empower patients to make better decisions and ultimately, improve patient health outcomes.6910111213

- Improved service quality: empanelment and proactive outreach help to ensure that patients receive care when they need it most and that no one gets left behind. Furthermore, such approaches help providers to balance their caseload, important for the delivery of timely, efficient services.6910111213

- Services for health literacy and self-care support: A PHM approach helps to promote services for health literacy, which give the patient the ability to play a more active role in their care process and put them in a better position to improve their own health. High health literacy is also linked to improved health outcomes and the rational and effective use of health services (i.e. a decrease in unnecessary care visits and a reduction in avoidable harm. Health literacy also works to push the government to address the most disadvantaged populations and their health needs when it comes to health literacy, ultimately helping to improve health equity.6910111213

- Effective utilization of services: the existence of formal linkages between facility and community-based providers helps to support the effective and rational use of promotion and preventive services. Community-based providers can help to alleviate patients from having to travel to a health facility if their care can be managed at the community level. This reduces the number of patients accessing facility-based services for conditions that can be treated at the community level, ultimately increasing the timely access to care at facilities. This bi-directional communication can also work to increase adherence to treatment plans.6910111213

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Explore this section for a curated list of actions that countries can take to improve population health management in their context, which embark on:

- Explaining why the action is important for population health management

- Describing activities/interventions countries can implement to improve

- Describing the key drivers in the health system that should be improved to maximize the success/impact of actions

- Curating relevant case studies, tools, &/or resources that showcase what other countries around the world are doing to improve as well as select tools and resources.

Key actions:

-

Empanelment is the organizational foundation for PHM and enables health systems to improve the patient experience, reduce costs, and improve health outcomes.12 By empaneling the target population, a point of care is established for individuals and simultaneously holds providers and care teams accountable for actively managing care for a specific group of individuals.

Key activities

National level

Determine the appropriate provider-to-panel ratio: there must be an adequate number of reliable providers to serve an empaneled population, thus provider supply is a crucial component in determining panel size. If supply and demand are unbalanced, PHM will not be feasible. While there are no guidelines or toolkits in LMIC on the appropriate provider-to-patient ratio for panels, care teams in Brazil and Costa Rica have managed panels of approximately 3500 and 4500 individuals, respectively.916 A study in the United States found that a single provider can reasonably manage care for 983 individuals, while a care team with substantial delegation may be capable of managing care for a panel size of 1947 individuals.17 These panel sizes are meant to be guidelines and not prescriptive as panel size depends on myriad contextual factors such as demographics, the burden of disease, and the capabilities of members of the care team.

Build multidisciplinary care teams: multidisciplinary teams have been the cornerstone of population health management and pursued in tandem with empanelment. Delegation of care between team members can result in more efficient and comprehensive care. delegating care to non-physicians on the team could help teams support double the size of a panel compared to care provided by a physician alone.17 It is important to note that delegation – or task shifting – should always be accompanied by the appropriate training for providers who assume new responsibilities.

Implement civil registration and vital statistics systems (CRVS): patient registers and civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) systems are crucial for care teams to locate, contact, and list their panel for planning purposes and must be coupled with medical record systems that enable a provider to track the health of individual patients in order to provide the most appropriate, continuous, and coordinated care.13 Recognizing that empanelment relies upon data on the relevant populations, the absence of civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) system may present a bottleneck to the establishment of patient panels. Without a CRVS system, stakeholders seeking to empanel their population may have to perform a census which is timely, costly, and often not within the scope of providers’ training.

Set-up capitation payment systems: capitation payment systems may enable providers to allocate time and resources based on the size and health needs of their panel. Capitation is common in many European countries with national health systems and universal patient registers. A recent study evaluated revenue gains under different payment models supporting patient-centred medical home models in the United States, finding that per-member-per-month payment (a type of capitation) increases practice revenue while increased fee-for-service payments do not.14

Facility and community level

- Create buy-in at the leadership and provider level: empanelment often requires a behaviour shift for all providers involved. In order to facilitate this change, facilities must have strong and engaged leadership and managers who can communicate the goals of empanelment and guide employees through new systems or processes.8

- Utilize the gatekeeping method: one way to promote continuous care is the gatekeeper method for accessing higher-level or specialist care for non-emergencies. In an “explicit” gatekeeper model, patients can only receive care from secondary or tertiary facilities if they first seek an approved referral from their primary care provider. By contrast, “implicit” gatekeeping occurs if patients are encouraged but not required to visit their primary care provider before seeking secondary or tertiary care.5

Gatekeeper systems

Gatekeeper systems help to facilitate primary care as the first point of contact and promote continuous, accessible, and coordinated care within a panel. In an “explicit” gatekeeper model, patients can only receive care from secondary or tertiary facilities if they first seek an approved referral from their primary care provider. In this way, primary care serves as the entry point to the health system and improves first-contact accessibility. By contrast, “implicit” gatekeeping occurs if patients are encouraged but not required to visit their primary care provider before seeking secondary or tertiary care.

can help reduce over-utilization of higher levels of care while ensuring that primary care providers are aware of all of the health needs of their panel, even when they must be addressed by specialists. This can improve coordination and continuity of care.

For successful gatekeeping, the following should be in place:

Clear communication of patient panels both between the health system and providers as well as between providers & their patients

Timely appointment availability at primary and speciality care facilities

Effective referral systems, including communication between levels of care

And geographically and financially available primary and speciality care services.

Sub-action 1. Use panel data to inform local priority setting

Key activities

Health systems level

- Review and update panel data: planners and implementers should routinely review and update panel data to build an empanelment system responsive to changing population health needs.

- Employ “panel maintenance”: panel maintenance, “involves a set of activities to ensure the delivery of primary health care services to all people and communities''1, such as determining panel size, assessing supply and demand, and optimizing continuity across the care continuum. Stakeholders can read more about panel maintenance activities and other implementation considerations for empanelment in the JLN’s overview on Empanelment: a Foundational Component of Primary Health Care

- Empanel population segments: always with the goal of working towards population-wide empanelment, countries can empanel population segments based on a population’s most pressing health needs and/or disadvantaged groups. These priority groups are all segments of the population that could be initially empaneled and would benefit from proactive services and monitoring by providers. For instance, a few community health workers may be responsible for all women of reproductive age within a given geographic catchment and provide these women with necessary referrals to prenatal care and birthing services, ensuring access to preventive services that may eventually result in a reduction in maternal mortality.

Related elements

- Policy & leadership

- PHC workforce

- Information & technology

- Purchasing & payment systems

- Adjustment to population health needs

- Primary care Primary care is “a key process in the health system that supports first-contact, accessible, continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated patient-focused care.” functions

Relevant tools & resources

- JLN, 2019: JLN’s overview on Empanelment: a Foundational Component of Primary Health Care

- Center for Care Innovations, 2016: Knowledge share - maximizing and sustaining empanelment

- Center for Care Innovations, 2016: Empanelment - toolkit for calculating panel size

- MEASURE, 2015: Civil Registration and Vital Statistics

- Safety Safety refers to the practice of following procedures and guidelines in the delivery of PHC services in order to avoid harm to the people for whom care is intended. Net Medical Home Initiative, 2013: Empanelment Implementation Guide

-

Community engagement Community engagement is the inclusion of local health system users and community members in all aspects of health planning, provision, and governance. It is a central component of ensuring that the services delivered are tailored to population needs, priorities and values, which can be achieved through the involvement of communities in the design, financing, governance, and implementation of PHC. To ensure that the needs of all community members are met, it is important that community engagement efforts include representation from diverse members of the community. This may require multiple mediums for engagement, to best capture the needs and opinions of traditionally underrepresented community members. is a central component of effective population health management and helps ensure that services are appropriately tailored to population needs and values. The WHO has defined community engagement as “a process of developing relationships that enable stakeholders to work together to address health-related issues and promote well-being to achieve positive health impact and outcomes.”12

Key activities

Community and facility level

- Implement basic forms of engagement: it may be helpful for health systems to begin by implementing more basic forms of engagement and planning strategies for scaling to more active engagement. These more basic forms of engagement include mechanisms like suggestion boxes or complaint lines

- Scale to more active engagement, if possible: when a basic level of engagement has been established, the next move would be to utilize more active forms of engagement as opposed to just passive methods. This can mean involving the community in decision-making processes, sign-off and increasing ownership. This will help to deepen engagement and yield the most person-centred services.

- Establish formal systems for feedback: in order to obtain constructive feedback from the community, there need to be formal systems in place not only to collect feedback, but to encourage, solicit, and respond to community members’ concerns, suggestions and needs.

- Utilize a village health committee: Village health committees have been shown to play a variety of roles in LMIC. These committees stand at the intersection between community engagement, social accountability, and facility management organization and leadership. A systematic review of leadership committees in LMIC found a number of common functions of such committees. Although these functions are all ideal, they may not be functional or feasible in all community committees:14

- Governance – to strengthen the accountability of the health facility to the community and public

- Co-management – of health facility resources and services

- Resource generator – in the form of material resources, labour, and funds for health facility

- Community outreach – to help the health facility reach into the community for the purpose of health promotion and improving health-seeking behaviour

- Advocacy – to act as a community voice to advocate (e.g. to local politicians and health managers higher up the health system) on behalf of the health facility

- Social leveller – to help mitigate social stratification by empowering marginalized sections of the community/public

- Support community advisory boards: community advisory boards often fulfil similar functions as village health committees, but may focus more on facility management and oversight as opposed to community engagement. These boards may also engage in community-based participatory research or approval of research.15 Other systems for community engagement include community meetings, feedback forms at facilities and/or community centres, and the integration of community members in health system planning and management activities.

- Promote collaboration between facility- and community-based providers:

- Role clarification: consider the skills and training for each member of the care team as well as rules and regulations within the facility. Stakeholders can then begin to delegate necessary clinical and administrative tasks between team members. Be sure that providers capable of delivering a range of services are available in the facilities at all times in order to facilitate patient access to services and promote integration and comprehensiveness.

- Effective performance management and supportive supervision: systems for individual-level provider performance management should incorporate provider perceptions and involve collaboration between providers and managers to develop actionable improvement plans. Traditional supervision often focuses on inspection and line management, resulting in punitive or corrective action and negatively affecting provider motivation and satisfaction. Supportive supervision instead aims to build pathways to improvement through active collaboration between providers and supervisors.

- Establish referral networks: referral management systems can reduce care fragmentation and improve the quality of referrals and transitions. A two-way referral system is organized to establish effective communication between physicians within the same and at different levels of the health system. The provider receiving the referral is required to refer the patient back to the referring provider (ideally the patient’s primary care provider) with clear feedback on the care encounter, any treatment provided to the patient, and what needs follow-up and continued management. Referral systems should align with empanelment and gatekeeping structures in place, and promote bidirectional referrals

Sub-action 1. Implement patient and family advisory councils (PFACs)

One example of robust community engagement is Patient and Family Advisory Councils (PFACs), a strategy that can improve patient-provider respect and trust by establishing and recognizing community members as key contributors to the health systems. In PFACs, community members meet with providers to discuss quality improvement and facility interventions to improve patient care.16

Key activities

Facility level

- Establish a PFAC team within the facility: the providers in the PFAC should be champions for community engagement in the health system. Roles and responsibilities for the providers within the PFAC include a leader to manage the PFAC, a logistics coordinator, a community recruitment coordinator, and a scribe.16

- Define the mission, vision, and goals of the PFAC: these components will eventually be discussed and formed by the community members as well, but it may be helpful to establish the baseline mission, vision, and goals between provider members to ensure alignment.16

- Coordinate meeting logistics: the providers should consider how and when PFAC meetings are held. Some important considerations to ensure inclusion include transportation, reimbursement, and child or elder care.16

- Identify patient and family advisors & recruitment: the PFAC team should next consider how they want to select community members. It is important to include patients who have some familiarity with the practice and are willing to contribute their feedback. Providers can be asked for suggestions. The best methods for contacting potential members will depend on context but may include: email, patient portals, regular mail, notices in newspapers, or through community-based organizations.16

- Coordinate invitations and the first meeting: identify and consolidate materials to orient patients to the goals of the group. During the first meeting, important topics include introductions, discussion and feedback on the mission, vision, and goals, and establishing topics or agendas for the next few meetings.16

- Ensure sustainability: some suggestions for ensuring that PFACs are sustainable include: allocating staff time and resources to PFACs, sharing information on feedback from the PFAC and how it was incorporated with communities, recognising and actively appreciating the contributions of community members to these groups, ensuring that patient members are diverse and represent all segments of the population.16

Related elements

- Adjustment to population health needs

- Multi-sectoral approach

- PHC workforce

- Policy & leadership

- Organisation of services

- Primary care Primary care is “a key process in the health system that supports first-contact, accessible, continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated patient-focused care.” functions

Relevant tools & resources

- WHO, 2022: Promoting participatory governance, social participation and accountability

- Social Pinpoint, 2021: How to get more citizens to participate in community engagement

- WHO, 2020: Community engagement Community engagement is the inclusion of local health system users and community members in all aspects of health planning, provision, and governance. It is a central component of ensuring that the services delivered are tailored to population needs, priorities and values, which can be achieved through the involvement of communities in the design, financing, governance, and implementation of PHC. To ensure that the needs of all community members are met, it is important that community engagement efforts include representation from diverse members of the community. This may require multiple mediums for engagement, to best capture the needs and opinions of traditionally underrepresented community members. : a health promotion guide for universal health coverage in the hands of the people

- UNICEF, 2020: Minimum quality standards and indicators for community engagement

- The Global Fund, 2020: Community Engagement Toolbox

- World Bank, 2018: Community enagement strategies

- WHO, 2017: Community Engagement Framework for Quality

- WHO, 2017: Community Engagement Framework for Quality, People-Centered and Resilient Health Services

- AHRQ, 2016: Patient and Family Engagement in Primary Care

- WHO, 2015: Technical Series on Safer Primary Care:

Patient engagement

Patient engagement is a partnership between patients and their care team. It combines patient activation with interventions to promote positive health behaviours, such as obtaining preventive care or engaging in regular physical exercise. The focus on activation and engagement rather than compliance recognizes that patients manage their own health most of the time and need to be able to make informed decisions about their own health.

- National Partnership for Women & Families, 2013: Patient and Family Advisory Councils

- USDN, 2012: Digital Sustainability Conversations How Local Governments can Engage Residents Online

-

Outreach services and systems are often preventive or promotive and initiated by the health system rather than by patients. When done effectively, proactive population outreach can help to improve the population's awareness of PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. in their community, increase efficiency, and optimize health and well-being by promoting person-centeredness and bringing services to patients.

The key questions when implementing proactive population outreach activities are 1) which patients, 2) which services, and 3) by whom (answered via the key activities below)

Sub-action 1. Identify which patients to contact

Health system stakeholders must define which patients they will contact for proactive population outreach. However, it may not be feasible to provide proactive population outreach to all patients initially. Implementers can begin the process of proactive population outreach by identifying segments of the population that have specific needs that can be addressed and managed in community settings.

Key activities

All levels

- Update patient registries: in order to identify which patients to contact, providers need to have actively and continuously updated patient registries to track the specific health needs of the population. This requires the presence of a CRVS, as discussed above in the empanelment action. However, implementers can leverage existing health information systems that collect population health data in the absence of a CRVS.

- Treat acute needs of the community: patients within any given catchment will have a diverse set of needs, so promoting initiatives that target these needs is important. Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) is an example that addresses the acute needs of the community. The steps to implementation include: adapting an approach to child health in national health policy, adapting clinical guidelines to country needs, upgrading care by training health workers in local clinics, ensuring the availability of necessary equipment and medicines, strengthening hospital care for children who cannot be treated in communities or clinics, and developing concurrent initiatives to strengthen preventive care.17

- Target patients by preventive need: preventive services are particularly strong opportunities for community-based outreach because they often do not require significant diagnostic knowledge or training and can be carried out by community-based providers with specific but limited knowledge. The specific preventive services that should be delivered in a given community will differ between groups and should be determined through consideration of demographics and the burden of disease within the catchment. For example, preventive care may be specific to age, gender, vulnerability such as poverty or malnourishment, or tuberculosis contact. Vaccines or routine care such as cervical cancer screenings are examples of preventive services that may be delivered to target populations during population outreach.

- Target by chronic disease: population outreach may be an effective strategy for ensuring that patients with chronic diseases have the necessary support and medications. For instance, community health workers may facilitate antiretroviral treatment adherence for HIV-positive patients or provide medication for diabetes management directly in their communities. See above for a case study on “home talks” in Uganda and how it resulted in positive learning and behavioural changes.18

- Target patients by risk strata: Determining target groups for population outreach according to risk profile (for morbidity or mortality) can improve coordination of care and direct resources towards those in the greatest need. Essential activities for ensuring comprehensive care for these patients include: developing a method for risk stratification, working as a team to assess patient needs, building care treatment plans, and coordinating care among all providers. After defining target outcomes of interest, stakeholders can conduct risk stratification using a variety of methods including algorithm-based tools using data from health records, referrals from providers, or a combination of these approaches.19

- Target outreach efforts to migrant populations: Migrant populations are another community that can benefit from targeted outreach efforts. Often, migrants are excluded from entitlements to health services and financial protection in health.2021 Further, some subgroups, especially refugees, have a greater burden of disease than the indigenous population.2223 To address migrant populations’ specific health needs and improve their access to care, many governments have implemented specialized community-based health interventions.

Sub-action 2. Identify which services to provide and who should provide them

When planning proactive population outreach activities, stakeholders should consider which services can be provided effectively outside of the facility. Another important consideration is which providers are capable of delivering proactive population outreach. Often, certain cadres within a multi-disciplinary care team – such as community health workers (CHWs) – have designated outreach roles. Stakeholders can begin to decide which individuals are most suited to carry out these activities

Key activities

All levels

- Use population health data to determine which services to focus outreach efforts around: while every context is different and these areas should be adapted based on one’s context, the following have been identified as specific services that could be effectively delivered in communities and homes by community health workers (CHWs):91

- Recognition, referral, and treatment of serious childhood illness by mothers and/or trained community-based providers

- Routine visits to homes to identify community members in need of specific health services

- Routine visits to homes to provide health education

- Facilitator-led participatory women’s groups

- Health service provision at outreach sites by mobile health teams

- Employ community case management: CHWs can employ this approach, which has been shown to reduce childhood mortality24 The World Vision Sustainable Health toolkit on community case management provides comprehensive information on program quality, essential resources, curricula, strategic frameworks, and focuses on malaria, diarrhoea, and pneumonia programs.24

- Assess supplies: before implementing any of these services within the community, it is important to consider what medicines and supplies will be needed in order to do so. Other important factors to consider are whether they can be easily transported, if they require refrigeration, if they require electricity or if they require running water24

- Utilize task-shifting: When selecting providers to deliver proactive population outreach activities, countries may consider task shifting to different cadres of providers, commonly CHWs. Many services provided in communities and homes can be delivered by providers with less training than doctors or nurses. It’s also important to think about whether providers have the competence and training to deliver community-based care and how providers will be supervised and trained to do so, if not. It’s also important to integrate them into the health system to ensure continuity

- Ensure robust referral systems are in place: it is important to ensure that there are clear referral pathways in place and that providers receive comprehensive training. PPO activities backed by two-way referral systems can contribute to improved care coordination between communities, facilities, and higher levels of care and ensure the delivery of safe, quality care.

- Collect feedback from the community: selecting providers for proactive population outreach is also an opportunity to solicit and respond to community values and opinions. Community members may have preferences regarding the providers’ proximity to the community or other traits. For instance, in Ghana, evaluations of the CHPS pilot program found that the community preferred that Community Health Officers be from the general area so they are familiar with the customs, values, and language of the community but also felt it was important that they not live directly in the community to avoid any concerns about confidentiality that may compromise trust and ultimately the quality of care.25

Related elements

- Adjustment to population health needs

- Multi-sectoral approach

- PHC workforce

- Policy & leadership

- Organisation of services

- Primary care Primary care is “a key process in the health system that supports first-contact, accessible, continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated patient-focused care.” functions

Relevant tools & resources

- WHO, 2022: CRVS systems

- WHO, 2022: Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI)

- THET, 2020: Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) Toolkit for Health Partnerships

- PHCPI, 2017: Summary of 15 steps & milestones for CHPS implementation

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2017: Closing the loop on patient referrals in health care

- World Vision, 2014: Community case management toolkit

- PLOS, 2013: Assessing Early Access to Care and Child Survival during a Health System Strengthening Intervention in Mali: A Repeated Cross-Sectional Survey

- AJMC, 2013: Risk stratification methods for identifying patients for care coordination

- Grouphealth, 2013: Closing the loop with referral management

- WHO, 2007: Task shifting: rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams

-

Health literacy supports and empowers individuals, families, and communities to manage and make informed decisions about their health and well-being when not in direct contact with health services. (6,13) When individuals are confident in their ability to make informed health decisions, they are often able to stay well longer and better manage any long-term conditions.

Key activities

National and subnational level

- Integrate health literacy into planning activities: it is important to develop and implement policies with health literacy in mind. Integrate health literacy into planning, evaluation, and patient safety and quality improvement efforts. Ensure goals are set for improving health literacy26

- Allocate funds for health literacy: ensure that the budget includes space to promote and strengthen health literacy within the population26

- Prepare the workforce to be health literate: promote health literacy training for the workforce and ensure there is a diversity of skill-sets and experience when it comes to health literacy. Set targets for where the workforce should be in health literacy26

- Meet the needs of the population: include the populations being served in the planning and execution of health literacy efforts. Always ensure the population's need is met by offering a diverse range of health literacy materials to meet the population where they are26

Facility and community level

- Health literacy awareness: in order to improve health literacy within a population, it is important that providers are not only aware of health literacy and the ways it can benefit patients, but fully understand where the root causes of health literacy lie and how to target them27

- Improve provider communication: understanding health literacy is not enough, providers must be able to fully and accurately communicate on the subject of health literacy and why it is vital to a patient’s care process. Easy and clear communication helps patients to gain more knowledge about their health conditions and in turn, make more informed decisions about their care27

- Employ the “teach-back” method: providers can be sure they communicated clearly and effectively by asking the patient questions about their condition that are pertinent to the care process27

- Ensure materials are digestible: if a patient receives a document about their care that employs highly medicalized language or refers to complex medical nomenclature, they are unlikely to understand exactly what is needed to make informed care decisions. Using plain and digestible language, as well as easy-to-read pictures or diagrams, can help to clearly communicate care needs to the patient.27

Reliable, high-quality, and accessible health information: Written and spoken information is clear and easy to understand. Complex and highly medical language is avoided. It is also readily available in different languages and formats, where relevant.613

Skilled, motivated, and accessible care teams: Care teams provide person-centred care and support shared decision-making. Care teams are dynamic, yet understand their respective roles and responsibilities to best support their patient population.613

Well-designed PHC centres: Facilities are easy to find, easy to navigate, and designed for the patient. There are helpful signs and information centres that patients can utilize when seeking care at PHC centres.613

To promote self-care and health literacy, PHC centres and/or care teams should provide:613

Telehealth services (tele-consults, internet-based chat rooms, virtual support groups, etc.)

Printed resources (pictograms, pamphlets, brochures, etc.)

In-home electronic aids (blood pressure cuff, blood glucose devices, etc.)

One-on-one patient education (i.e. a dedicated health care worker who is responsible for providing this support)

Peer support groups for different chronic conditions

Related elements

- Adjustment to population health needs

- Multi-sectoral approach

- PHC workforce

- Policy & leadership

- Organisation of services

- Primary care Primary care is “a key process in the health system that supports first-contact, accessible, continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated patient-focused care.” functions

Relevant tools & resources

- WHO, 2022: Improving health literacy

- Canberra Health Literacy: 2021: What is health literacy?

- Contemporary Pediatrics, 2018: 3 steps to boost health literacy

- WHO, 2013: Health literacy: the solid facts

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Understanding and identifying the drivers of health systems performance--referred to here as “related elements”--is an integral part of improvement efforts. We define related elements as the factors in a health system that have the potential to impact, whether positive or negative, population health management. Explore this section to learn about the different elements in a health system that should be improved or prioritized to maximize the success of actions described in the “take action” section.

While there are many complex factors in a health system that can impact population health management, some of the major drivers are listed below. To aid in the prioritization process, we group the ‘related elements’ into:

Upstream elements

We define “upstream elements” as the factors in a health system that have the potential to make the biggest impact, whether positive or negative, on policy & leadership.

- PHC Workforce

-

Successful empanelment requires a sufficient and well-trained workforce to empanel patients into. Provider supply is a crucial component in determining panel size and composition. There must also be an adequate supply of appropriately trained, reliable, and available community-based providers to effectively provide community-based proactive outreach and care, a key component of effective population health management.

Learn more

- Service Availability & Readiness

-

Understanding which specific services are offered and available in relevant health care settings is critical prior to engaging in proactive population outreach and prior to empaneling patient populations to the appropriate facilities.

Learn more

Complementary elements

We define “complementary elements” as the factors in a health system that have the potential to make an impact, whether positive or negative, on population health management. However, we consider these drivers as complementary to, but not essential to performance.

- Policy & Leadership

-

National policies supportive of a population health management approach will aid decision making and service delivery, help enable local stakeholders to implement systems for community engagement, and aid in the implementation of empanelment systems.

Learn more

- Information & Technology

-

Information systems can be complementary to successful local priority setting when they can effectively collect, track, and report data that is relevant to the local level. Successful empanelment can be supported by information systems with broad, fundamental capacities to identify, stratify, and track a given patient population. Surveillance systems provide data that supports the identification of populations in need of proactive population outreach services.

Learn more

- Multi-sectoral Approach

-

Social accountability provides a mechanism for citizens and civil society, together with service providers and government, to identify and seek solutions to the specific problems they observe within their local health system. It also builds an enabling environment for citizen-led accountability and decision making.

Learn more

- Adjustment to Population Health Needs

-

National priority-setting exercises that allow flexibility and encourage adaptation at a local level help to facilitate local priority setting.

Learn more

- Management & Organisation of Services

-

Strong facility leadership is necessary to ensure that strategic action plans and community engagement translate to actionable and tangible changes at the facility level. When it comes to the organisation of services, care teams help to facilitate the delivery of high-quality services to patient panels. Additionally, effective proactive population outreach is supported by appropriately trained, reliable, and available community-based providers who are integrated into local care teams to ensure coordination and continuity of patient care.

Learn more

- First-contact Accessibility

-

First contact accessibility is complementary to population health management initiatives, including empanelment and proactive population outreach, by ensuring that PHC is the entry point to the health system and a patient’s first point of care when seeking health services.

Learn more

- Coordination & Continuity

-

Coordination of care is a complementary strategy to creating and maintaining empanelment systems and appropriately reaching the populations being served. Similarly, continuity of care is a complementary strategy to creating and maintaining empanelment systems and bringing services to the community through proactive population outreach.

Learn more

- Financial Protection

-

Patient lists for empanelment can be generated by financial coverage schemes. Financial coverage can promote the provider or facility each patient is empaneled to as the first point of contact through gatekeeping or other mechanisms.

Learn more

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Countries seeking to improve population health management can pursue a wide array of potential improvement pathways. The short case studies below highlight promising and innovative approaches that countries around the world have taken to improve.

PHCPI-authored cases were developed via an examination of the existing literature. Some also feature key learnings from in-country experts.

- East Asia & the Pacific

-

- Austrailia: Refugee health program

- Indonesia: Puskesmas and the Road to Equity and Access

- Europe & Central Asia

- Latin America & the Caribbean

-

- Brazil: The Family Health Program

- Brazil: Building a national community health worker programme

- Brazil: Using participatory budgeting to amplify patient voices

- Brazil: A Community-Based Approach to Comprehensive Primary Health Care

- Costa rica: Empanelment in 1990s reforms

- Cuba: Emphasis on community-based primary care in a tiered system improves outcomes

- Peru: Pursuing Universal Health Coverage Through Local Community Participation in Peru

- Middle East & North Africa

- North America

- South Asia

-

- Nepal: Strengthening Nepal's female community health volunteer network

- India: Decentralized government and community engagement

- India: Establishing community participation and decision-making power in local health systems

- Kerala, India: Decentralized governance and community engagement to strengthen primary care.

- Sub-Saharan Africa

-

- Ethiopia: Strengthening Primary Health Care Systems to Increase Effective Coverage and Improve Outcomes in Ethiopia

- Ghana: Increasing access to community-based primary health care services

- Ghana: CHPS policy

- Ghana: Educational interventions - home talks

- Ghana: Community-based health programs

- Mali: Proactive case community management in urban settings

- Mali: Community-based care in Mali

- Namibia: Reducing health inequity through commitment and innovation

- Rwanda: Nationwide implementation of integrated community case management of childhood illness in Rwanda

- Multiple regions

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Building consensus on what effective population health management looks like and key strategies to fix gaps is an important step in the improvement process. Below, we define some of the characteristics of effective population health management in greater detail:

-

“Empanelment (sometimes referred to as rostering) is a continuous, iterative set of processes that identify and assign populations to facilities, care teams, or providers who have a responsibility to know their assigned population and to proactively deliver coordinated primary health care towards achieving universal health coverage.”1 It is the organizational foundation for population health management and enables health systems to improve the patient experience, reduce costs, and improve health outcomes.12 Empanelment establishes a point of care for individuals and simultaneously holds providers and care teams accountable for actively managing care for a specific group of individuals. Empanelment also provides a population denominator so stakeholders can more easily interpret data, track performance, and effectively plan services. Empanelment is synonymous with “rostering,” and “catchment” or “panel” refers to the population assigned to a care team, but not the provision or management of care for that group.

There are numerous reasons why stakeholders may determine that empanelment would be a worthwhile intervention. Empanelment can improve health outcomes by ensuring responsibility for a group of patients regardless of if they seek care, rather than reactively treating patients who access health services. Empanelment also gives stakeholders a stable and updated “denominator” to understand the population for which a primary health care clinical service unit is responsible. Empanelment creates a process for knowing and understanding who and which communities the clinical teams are accountable and responsible for overtime. Without understanding this baseline measure, and the segments of the population (numerators) that make up this denominator, it is difficult to effectively plan and implement population health strategies. Further, in order to shift PHC service orientation from a purely reactive one to proactive over time, empanelment is necessary and will make proactive population outreach more effective.

There are three general approaches that countries can use to both identify the target population and assign a panel to a facility, care team, or provider: geographic, insurance-based, or individual choice (though other forms can exist, including empanelment to private provider groups).1 These methods are not mutually exclusive and can occasionally co-exist:

- Geographic empanelment uses pre-existing geographic or municipal boundaries to assign individuals to a provider or care team. While this is the simplest method of empanelment and supports strong geographic access to PHC, it may be perceived as limiting the autonomy of patients to choose their providers and subsequently decrease patient trust in the system. Geographic empanelment is also dependent on PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. provided by a governmental entity, and low rates of private PHC use.

- Insurance-based empanelment uses insurers to assign individuals to a panel. Insurers may elect to use gatekeeping schemes to manage patient referrals and access to services beyond the PHC level. Insurance-based empanelment can work in a variety of public, private, or mixed systems, but it is dependent on a formal insurance entity and broad universal health coverage by that entity or mix of entities. While insurance-based empanelment can be an effective approach to empanelment, individuals may not always adhere to their insurance-based assignment which leads to gaps in continuity of care. In addition, in countries with a large number of its population uninsured, for example in countries without a national health insurance scheme, this approach runs the risk of missing individuals and families lacking insurance coverage.

- Individual choice, often referred to as voluntary empanelment, prioritizes patient autonomy and allows patients to choose their provider or care team.2 Because this approach relies on patient choice and voluntary care-seeking behaviour, it may miss individuals and families who do not seek care, move often, or face other barriers to accessing care.

Once patients are linked to a provider or care team, a patient’s first point of contact has been clarified and should be deliberately reinforced during subsequent visits to the facility and during community-based care. (1)

Benefits of empanelment

Empanelment is an important foundation for population health management by which providers assume proactive responsibility for patient populations, regardless of whether patients visit the facility. In addition to providing logistical structure and clarity to patients, empanelment can enable a person-centred primary health care system that delivers the core functions of strong PHC: first-contact accessibility, continuity, coordination, and comprehensiveness. See the table below for more information on the role of empanelment in strengthening the core functions of PHC:

Table 1. Pulled from the Joint Learning Network’s overview on Empanelment: a Foundational Component of Primary Health Care. Available from: https://www.jointlearningnetwork.org/resources/empanelment-a-foundation…

While empanelment is a critical component, this must be achieved in conjunction with the other elements of population health management, namely local priority setting, community engagement, and proactive population management. When empanelment is not technically feasible, other parts of population health management can be prioritized until policy and community contextual elements enable empanelment to be implemented.

-

Collaboration between facility - and community-based providers refers to the process of these two subsets of providers working together to provide person-centred, coordinated care. This relies on the existence of formal linkages between facility- and community-based service delivery platforms.613 Strong linkages between facility- and community-based providers include the following attributes:

- Role clarification: Provider roles and responsibilities at different levels of care need to be clearly defined, understood, and enforced. Defining roles and determining the mix of providers within a care team involves consideration of the patient panel needs, the human resource supply, and national policies for care delivery. Considering the skills and training for each member of the care team as well as rules and regulations within the facility, stakeholders can begin delegating necessary clinical and administrative tasks between team members. However, when delegating responsibilities it is important to ensure that providers capable of delivering a range of services are available in the facilities at all times in order to facilitate patient access to services and promote integration and comprehensiveness. Coherent and unified teams should share a sense of collective responsibility and have well-defined but flexible roles and work procedures. Poorly defined roles can become a source of conflict and reduce the effectiveness of care40

- Two-way communication: not only does there need to be effective communication between the patient and provider, but effective population health management includes two-way communication channels between the facility and community, such as via the use of mobile phones and referral networks. It is important that facility and community providers are aligned on care pathways so as not to duplicate the care process and/or create a bottleneck in the delivery of care. Adequate transfer of patient information within and across levels of care (both up and down-referrals) is essential for the timely delivery of effective services and care coordination. When patients are seen by multiple providers without well-communicated transitions between team members, care teams may pose a barrier to continuity and the development of longitudinal patient-provider relationships. 34373839

- Integration: it is crucial that community-based providers are fully integrated into facility management structures, facility teams, and data systems. Care coordination is an important function for creating these linkages between health and non-health sectors and networks within and among levels of care (i.e. horizontal and vertical integration) that support PHC in effectively meeting the complex needs of patients throughout their life course. Without full integration of community-based providers, the care system and process become fragmented and often duplicative.

- Performance management: it is important to ensure that supportive supervision and training opportunities are available to both facility- and community-based providers. Supervisors should be trained on how to coach, mentor, communicate, and conduct performance planning. Additionally, supervisors can be taught adult learning and training techniques to improve their skills. However, it is important to note that supportive supervision may only be effective if providers have a baseline level of support such as adequate drugs and supplies, human resources, workload, incentives, and career development.

- Coordination Coordinated care includes organizing the different elements of patient care throughout the course of treatment and across various sites of care to ensure appropriate follow-up treatment, minimize the risk of error, and prevent complications. Coordination of care happens across levels of care as well as across time, and often requires proactive outreach on the part of health care teams as well as informational continuity. : coordination of care relies on proactive outreach on the part of health care teams and robust information and communication systems within and across levels of care. To this end, it is important that providers are in close geographic proximity to each other and refer patients back and forth between the facility- and community level, depending on patient needs. Well-coordinated care lends itself to improved health outcomes and a better patient experience.

In order to support the strong functioning of the attributes listed above, they need to exist in a setting where national and regional guidelines are present that clearly define the roles between the different service delivery platforms to ensure each platform's respective functionality is clear. Highlighting and defining their different capabilities is important in promoting well-coordinated care. Robust information systems and referral networks also must be in place. Setting up a bi-directional communication structure between facility and community providers is critical and referral networks help not only with communication continuity, but informational continuity as well. Finally, supportive, trusting relationships between patients and providers are essential for effective population health management. Fostering a predictable and coherent environment for both providers and patients promotes patient-provider trust and communication as well as patient satisfaction. Skilled, motivated providers also must be present at the community- and facility-level to ensure a culture of collaboration and teamwork is ever-present.

-

Community engagement Community engagement is the inclusion of local health system users and community members in all aspects of health planning, provision, and governance. It is a central component of ensuring that the services delivered are tailored to population needs, priorities and values, which can be achieved through the involvement of communities in the design, financing, governance, and implementation of PHC. To ensure that the needs of all community members are met, it is important that community engagement efforts include representation from diverse members of the community. This may require multiple mediums for engagement, to best capture the needs and opinions of traditionally underrepresented community members. is the inclusion of local health system users and community resources in all aspects of design, planning, governance, and delivery of health care services. Community engagement Community engagement is the inclusion of local health system users and community members in all aspects of health planning, provision, and governance. It is a central component of ensuring that the services delivered are tailored to population needs, priorities and values, which can be achieved through the involvement of communities in the design, financing, governance, and implementation of PHC. To ensure that the needs of all community members are met, it is important that community engagement efforts include representation from diverse members of the community. This may require multiple mediums for engagement, to best capture the needs and opinions of traditionally underrepresented community members. is a central component of effective population health management and helps ensure that services are appropriately tailored to population needs and values. The WHO has defined community engagement as “a process of developing relationships that enable stakeholders to work together to address health-related issues and promote well-being to achieve positive health impact and outcomes.”12 Community engagement Community engagement is the inclusion of local health system users and community members in all aspects of health planning, provision, and governance. It is a central component of ensuring that the services delivered are tailored to population needs, priorities and values, which can be achieved through the involvement of communities in the design, financing, governance, and implementation of PHC. To ensure that the needs of all community members are met, it is important that community engagement efforts include representation from diverse members of the community. This may require multiple mediums for engagement, to best capture the needs and opinions of traditionally underrepresented community members. is a critical function and enabler of strong PHC systems. When done effectively, community engagement helps to ensure that the design, planning, and delivery of health care services appropriately meet the needs of the communities they are designed to serve. This can help systems to achieve:

- Effective local priority setting

- Positive health impact and outcomes

- Stronger patient-provider respect and trust

- Person-centred care models

- Increased utilization of care by the community

There are two central considerations when planning community engagement:

- Where and when to integrate community engagement

- How to integrate community engagement

Ideally, community engagement should be integrated into all aspects of health design, planning, governance, and delivery.41 The WHO’s Community Engagement Framework for Quality, People-Centered and Resilient Health Services describes how health systems can engage with communities to ensure integrated, people-centred and resilient services. Specifically, the framework identifies key areas where community engagement practices, processes, and procedures can be embedded to support better engagement between health systems and communities, including:12

Capacities for shared assessment and analysis of the situation

- Capacities to design context-specific approaches

- Capacities for shared agenda setting and planning

- Capacities for defining roles and responsibilities

Learn more about the WHO’s Community Engagement Framework here.

-

Proactive population outreach is the active provision of care in homes or communities rather than exclusively in facilities. These services are often preventive or promotive and initiated by the health system rather than by patients. Community health workers (CHW) or similar cadres of providers most often engage in proactive population outreach and conduct health promotion activities, education, identification of acute cases and pregnant women needing referrals to health facilities, community integrated care for common adult and child illnesses (ICMI), family planning provision, chronic disease adherence follow-up, risk-stratified care management, and even palliative care in communities or homes. When done effectively, Proactive population outreach can help PHC systems to:

- Improve the population’s awareness of access to PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers.

- Increase efficiency by moving certain health activities outside of the physical clinic

- Optimize health and well-being in ways that are person-centred by bringing services to patients and integrating delivery in the context of the community

Often population outreach begins through targeting or stratifying a segment of an empaneled population to receive particular services. Some of these segments may include patients who require specific services for preventive care or specific disease-based care, or because they are high-risk patient populations. The goal of proactive population outreach is to ensure that the population is aware of and accesses services, to increase efficiency by moving certain health activities outside the physical clinic, and to optimize health and well-being in ways that are person-centred by bringing services to patients and integrating delivery into the context of the community.11

-

Services for health literacy and self-care refer to primary care services and processes that support and empower individuals, families, and communities to manage and make informed decisions about their health and well-being when not in direct contact with health services.613 When individuals are confident in their ability to make informed health decisions, they are often able to stay well longer and better manage any long-term conditions. Having poor health literacy can be detrimental to people later in life and lead to overuse of care services, as well as experiencing complications and/or harm that would have otherwise been avoidable.44 More specifically, health literacy means that people have the knowledge, personal skills, and confidence to61327:

- Navigate: It is important that people can easily locate their PCP or care team upon arrival at a care facility. Health literacy also means that individuals are ready and able to fill out any forms required to get insurance and/or needed primary care services.

- Communicate: People feel empowered to share their health information with their care team and actively participate in their care plan. For example, patients might ask their care team--what is my health condition? What do I need to do to self-manage it? Why is it important for my long-term health and well-being? They are also able to effectively answer questions about their own care when asked by a provider.

- Practice self-care: people can actively promote their own health, prevent disease, maintain health, as well as cope with illness and disability with or without the support of their care team. They can function independently on this front and are aware of what is needed to promote their personal well-being.

- Make informed, numerate decisions: People are able to measure and appropriately deliver medications and analyze the relative risks and benefits of different treatment/health plans. They understand dosing and can effectively administer their own care plan when needed. They also feel confident to communicate, assert, and enact these decisions and plans with their care team. They know what questions to ask and are ready to ask for more direction or information when they feel something is unclear.

Health literacy, including one’s ability to navigate, communicate, practice self-care and make informed decisions, is often influenced by the following: personal characteristics of people (their values and beliefs), the social determinants of people (their race, education level and income status etc.), and the physical determinants of people (the settings in which they work and live). In other words, it is the result of both individual features and physical or environmental features6134445

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

References:

- The Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage Person-Centered Integrated Care Collaborative. Empanelment and Panel Management: A Foundational Component of Primary Health Care (in progress).

- WHO. Community-based health care, including outreach and campaigns,in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 May 26]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/community-based-health-care-including-outreach-and-campaigns-in-the-context-of-the-covid-19-pandemic

- Unable to find information for 5937926.

- Ahmed S. A community-based approach is key to truly person-centred care – The Health Policy Partnership [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2020 May 27]. Available from: https://www.healthpolicypartnership.com/a-community-based-approach-is-key-to-truly-person-centred-care/

- McDonald J, Ollerenshaw A. Priority setting in primary health care: a framework for local catchments. Rural Remote Health. 2011 Jun 6;11(2):1714.

- WHO, UNICEF. Internal working draft: Primary health care performance: measurement for improvement- technical specifications. WHO; 2021 Oct.

- WHO. Transforming Vision into Action: Operational Framework for Primary Health Care. WHO; 2020 Dec.

- Armstrong K, Rose A, Peters N, Long JA, McMurphy S, Shea JA. Distrust of the health care system and self-reported health in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2006 Apr;21(4):292–7.

- Joint Learning Network, Ariadne Labs, Coimagine Health. Empanelment: A Foundational Component of Primary Health Care. Joint Learning Network; 2019.

- Unable to find information for 5716801.

- Freeman P, Perry HB, Gupta SK, Rassekh B. Accelerating progress in achieving the millennium development goal for children through community-based approaches. Glob Public Health. 2012;7(4):400–19.

- WHO. WHO Community engagement framework for quality, people-centred and resilient health services. World Health Organization; 2017.

- WHO. Primary health care measurement framework and indicators: monitoring health systems through a primary health care lens [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2022 [cited 2022 Mar 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240044210

- McCoy DC, Hall JA, Ridge M. A systematic review of the literature for evidence on health facility committees in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan. 2012 Sep;27(6):449–66.

- Nyirenda D, Sariola S, Gooding K, Phiri M, Sambakunsi R, Moyo E, et al. “We are the eyes and ears of researchers and community”: Understanding the role of community advisory groups in representing researchers and communities in Malawi. Dev World Bioeth. 2018 Dec;18(4):420–8.

- National Partnership for Women & families. Key Steps for Creating Patient and Family Advisory Councils in CPC Practices. 2013. Report No.: April.

- Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) [Internet]. The World Health Organization. [cited 2017 Sep 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/child/imci/en/