Indonesia

Key country characteristics

- Lower-middle income country in East Asia & Pacific

- Population: 270.6M

- GDP Per Capita: $12.3K

- Life expectancy at birth: 69

Indonesia, a geographically complex nation made of up an estimated 17,000 islands, is currently the fourth-most populated country with a diverse population of 264 million that speak 724 languages and/or dialects. The country faces the unique challenge of providing health care across 900-1000 inhabited islands and 34 provinces with a mix of public and private providers. 12 In the 1960s, recognizing the need to provide better health services to individuals and communities, Indonesia introduced puskesmas into the primary health care system. Puskesmas – community health centers that still function today – targeted primary health care gaps including primary care delivery, population health management, and geographic and financial access. 1 Over the next 50 years, Indonesia has faced challenges within its primary health system but has been able to adapt and respond to them by addressing challenges while still maintaining service delivery through the puskesmas network as a major source of primary care. The flexibility of the national approach to the puskesmas model is an example of continual improvement of the health care system, engaging multiple stakeholders to address identified gaps, and remaining a critical method for ensuring the successful rollout of Indonesia’s universal health care (UHC) program in 2019.

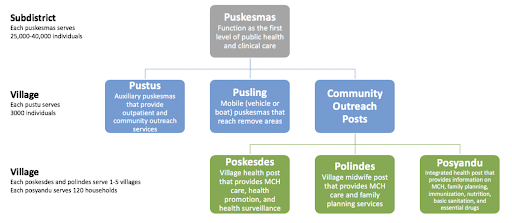

For the past fifty years, Indonesia has committed to providing access to primary health care to its citizens. With the creation of puskesmas, Indonesia mobilized its health care system to aim to integrate preventive and curative medicine, and for the subsequent 20 years, the government constructed health centers and hospitals around the country to support care delivery. 13 Seeking to improve geographic access across the country’s islands, the network of care extended to include auxiliary puskesmas (pustus), integrated health posts (posyandus), mobile puskesmas (pusling), village-level labor/delivery posts (polindes), and village health posts (poskesdes) (Figure 1). These additions to service delivery were in response to identified gaps in care: for example, in 1979, recognizing the need to expand to more remote areas, pustus were implemented at the village level to provide preventive and curative ambulatory care. 12 Similarly, puslings, or mobile clinics, were established so that populations that lacked access to formal health services were able to receive such services. 2

The primary role of puskesmas has not changed significantly over time, and they continue to be the infrastructure point that provides preventive, promotive, and curative care at the sub-district level with a focus on both the community and individual. 2 The puskesmas network provides six essential services: 1) Health promotion, 2) Communicable disease control, 3) Ambulatory care, 4) Maternal and child health and family planning, 5) Community nutrition, and 6) Environmental health. 3 One-third of puskesmas also provide basic inpatient care such as Basic Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care(2). Community health efforts of the puskesmas are geared towards preventive and promotive care while primary care focuses more on outpatient and inpatient services as well as home care. Puskesmas are given management assistance from the national level, in the areas of five-year development planning, monitoring and supervision, resource management, and leadership. Over time, the puskesmas network has continuously evolved to reflect identified challenges and incorporate new national initiatives as described below.

After the Asian financial crisis in 1997, Indonesia went through a period of decentralization. With decision-making shifting to the local government, the health system has faced challenges related to this change, such as a workforce unable to consistently deliver high-quality of care, limited resources particularly at the primary care level, growing health care demands of the population, and financial constraints. 1 To address these obstacles, the central government enacted a number of reforms addressing quality and financial access gaps.

In 2008, a set of Minimum Service Standards (MSS) for health were established that focused on primary health care, referrals, epidemiology and prevention, health promotion, and community empowerment. 2 These focused on four types of service which were primarily delivered at PC facilities: 1) 14 basic services at the primary care level, 2) appropriate referral services, 3) outbreak management within 24 hours, and 4) health promotion and community empowerment. Targets were set, and while the government tried to make the standards achievable for remote and urban areas, regional differences in achieving these goals were seen particularly in communities where the income level was lower thus making the standard unattainable. This was a particular problem in Papua where individuals who were members of nomadic tribes rarely visited puskesmas. Understanding the need to better the health of its citizens, in 2016, the government revised and established a new MSS that will go into effect in 2019. With the new MSS model, coverage for each target group is set at 100% for all populations, and innovative community outreach strategies have begun, such as Flying Health Care for hard-to-reach communities. The new standards cover 12 areas ranging from providing continuous health care across the lifespan, chronic disease monitoring treatment, HIV and TB monitoring and treatment, and mental health care. If a facility fails to reach its targets then the local government will face administrative punishment for the first two deviations and eventual replacement if they fail to complete services after one year.

Continuing to respond to the needs of the population and financial barriers, in 2004, the government implemented the National Act No. 40/2004 which established a National and Social Security System (SJSN). To operate the system, the SJSN Act was supplemented by Law 24/2011, which expanded the role of Badan Penyelenggara Jaminan Sosial-Kesehatan (BPJS-K), the country’s social health insurance resulting in a single-payer environment. BJPS-K is the public entity that runs the national health insurance program or Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional (JKN). 245 The JKN program was launched on 1 January 2014 by the BPJS-K, and puskesmas were mandated by law to be JKN providers whereas private providers had the option to join. Through this contract, capitation payments were established with the goal to improve the quality of service at the PHC level, particularly within the puskesmas network. 2 Examples of performance goals include a number of visits, non-specialist to outpatient ratio, visits with patients with chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, and home visits. Additionally, there is a profiling and credentialing process conducted by BPJS prior to a puskesmas officially contracting with BPJS and becoming part of the JKN program (Jet).

Recognizing that primary care teams and puskesmas are central components to service delivery facilitated by the implementation of JKN, empanelment (also known as rostering) was a strategy of JKN program. All community members must register with a puskesmas, PHC clinic, or local physician within the first three months of enrollment to JKN with their PCP acting as a gatekeeper to receiving higher levels of care. 1 In this model of care, individuals must visit their local puskesmas or primary care clinic in order to receive a referral, and the only exception is for emergency care. In general, JKN members are seeking their first point of contact at puskesmas, but referrals are done if the case is beyond one of the 144 competencies that primary care physicians must be able to treat.

Indonesia’s wide expanse of islands makes health care delivery a challenge. While the creation of the puskesmas network increased geographic access, some islands are so remote that it can take over ten hours to arrive by boat. With that came staffing difficulties, and 23% of puskesmas facilities were inadequately staffed as of June 2018. Staffing shortages ranged from 2.7% of puskesmas being without an adequate amount of nurses to nearly 44% of puskesmas lacking enough dentists. 6 Recognizing the need for human resources, in 2014, the government established the Nusantara Sehat (Healthy Archipelago) program, which deploys multidisciplinary health care teams to puskesmas in remote and border islands. In addition to providing care to remote areas and responding to their specific health needs, Nusantara Sehat also focuses on continuity of care, empowering the community, creating integrated health care, and increasing equitable health services. 7 The teams ensure that the puskesmas are functioning well and meeting targets, which better ensure adequate funding from the government in the future.

Each Nusantara Sehat team (NST) consists of nine types of healthcare workers including doctors, nurses, midwives, dentists, laboratory specialists, technicians, pharmacists, nutritionists, and environmental and public health professionals. Nusantara Sehat depends on volunteers with the younger generation being particularly interested in joining the program. Teams remain in their location for two years with the option to extend their time in the program but in a different location; clinicians change facilities in order to share knowledge learned from the previous puskesmas and improve the next one. As of July 2018, approximately 2800 health workers have been deployed to nearly 500 puskesmas. 7 In addition to the NST, individuals (NSI) can also participate in the program with slightly different requirements: for example, as part of an NST, clinicians are assigned to a given location based on their test (administrative and psychological) results whereas NSI can choose where they would like to be stationed. 8 Staffing resources in puskesmas are also strengthened by the family doctor program, a family care-specific curricula that primary care physicians can complete; currently, 100 puskesmas have physicians with this accreditation.

Coupled with the efforts of Nusantara Sehat is the Healthy Indonesia Program with Family Approach (PIS-PK). 9 This program (2015-2019) is a method of service delivery in the puskesmas network that targets comprehensiveness and first contact and ranges from covering 2000-7000 families. The Family Approach focuses on providing the family unit with preventive and promotive care and in particular: 1) strengthening promotive and preventive care as well as community empowerment, 2) improving access to health care through the optimization of the referral system with a focus on remote and border areas, and 3) the rollout of national health insurance, as previously described. 910 Each household is assessed as a whole, so if one family member is unwell then the health index of the household may be affected. Volunteers visit families and are particularly keen to reach those in high-risk neighbourhoods, for example, those who live near factories or especially remote areas. 7

There are 12 indicators that are measured through the program and include infant immunization and growth monitoring, TB treatment, hypertension therapy, mental illness monitoring and treatment, appropriate WASH standards, and smoking cessation. 8 By providing high-quality preventive care at the family level, the goal is to lower hospital visits and admissions. In addition to home visits, staff encourage stay-at-home mothers to gather weekly at the sub-district office where medical staff from puskesmas come to provide maternal and child care. Lastly, to address financial access, the government provides funds specifically for puskesmas in remote areas that serve poor communities. This focus on equity is important for the development of facilities in remote and border regions.

Strengthening the primary care system in Indonesia is ongoing, and incremental, yet important changes have occurred: Deliveries with skilled birth attendants increased from 43% in 1997 to 83% in 2012 with 64% of women completing one antenatal care visit during the first and second trimester and two visits in the third trimester; related, 9 in 10 mothers reported receiving care from a professional during pregnancy. 1112 Immunization coverage also improved with measles vaccination increasing from 60% to 77% and a similar improvement in DTP3 rates. 11 The infant mortality rate decreased from 22/1000 live births in 2000 to 14/1000 live births in 2015, and maternal mortality dropped from 265/100,000 live births in 2000 to 126/100,000 live births in 2016, but despite these gains, Indonesia missed MDG 5. 13

As of 2018, there are 9825 puskesmas that employ thousands of health care workers at the village level and that generally have a catchment area of 25,000-40,000 individuals. 25 This broad network of services and a model of care designed to provide empanelled team-based care has strengthened the capacity of community public and preventive health as well as health promotion efforts. Through the placement of hundreds of NST/NSI and the Healthy Indonesia Program workers that staff and augment puskesmas, the performance of PHC facilities within this network improved coverage in even the most remote areas targeted. 7 However, despite an impressive increase in puskesmas facilities since their inception and Nusantara Sehat, major regional disparities remain, and 430 sub-districts lack puskesmas, mostly in rural areas outside of Java. 1 Indonesia’s diverse population that spans thousands of islands creates both transportation obstacles and differences in culture and language that make access to care more difficult. However, community outreach efforts persist, and local working groups provide special services, for example, health services for commercial sex workers and children living on the street.

Despite the focus on quality and models of care, the functioning of puskesmas within the JKN program is also highly variable. As of 2018, approximately 60% of individuals were registered in puskesmas, 21% in other primary clinics, and 19% in private practices. Despite puskesmas acting as the first point of contact, clinicians provide acute treatment more often than longitudinal preventive care. Reasons for this include incentives for good performance that is more often related to curative care that is then evaluated through assessments conducted by BPJS. Additionally, out-of-pocket spending remains high due to a lack of coverage by JKN, some facilities face inadequate staffing, and weak provider/patient relationships persist; these challenges affect the ability to provide continuous care throughout a patient’s lifetime. 1

Similar to many countries across the globe, Indonesia also faces emerging health challenges as its population ages: chronic diseases such as hypertension, cancers, and diabetes are on the rise while there remains ineffective control of infectious diseases like malaria and drug-resistant tuberculosis. Further compounding the problem is the reemergence of diseases including polio and diphtheria. Puskesmas are trying to meet these growing health needs, and their scope expanded to include coverage of noncommunicable and other chronic diseases. 45 This work was supported nationally including the creation of a national NCD prevention unit and posbindus to allow for community participation to detect and monitor those with NCD risk factors. 1 Additionally, there is an effort to improve existing facilities and upgrade some to provide basic emergency obstetric and neonatal care. 2 Further, an accreditation process began in 2014 to assess PHC services, commitment to environmental health, and community outreach. 1 The goal is to accredit 5600 facilities by end of 2019 - early 2020 with 5227 having been accredited in 3966 sub-districts in 2018, 38 of which are in remote Papua. 2

Indonesia plans to address persistent disparities in access and quality by filling the remaining gaps in care coverage and improving the quality of care through the puskesmas network. This commitment to building primary care services for all and the capacity to learn and evolve has continued to be evident through the series of financial reforms, ongoing efforts to address the growing demands from chronic disease and the threat of reemerging diseases and creative approaches to expand physical access. 5 Workforce efforts to build and expand the reach of NST multidisciplinary teams will need to continue in order to meet growing demands.

Indonesia’s puskesmas have helped to build the foundations of a wider-reaching primary care delivery system. In order to meet UHC and SDG health goals, this foundation will need to be continually strengthened with better trained, motivated, competent, and responsive workforces that have the tools and resources to meet ever-growing health needs and challenges in Indonesia.